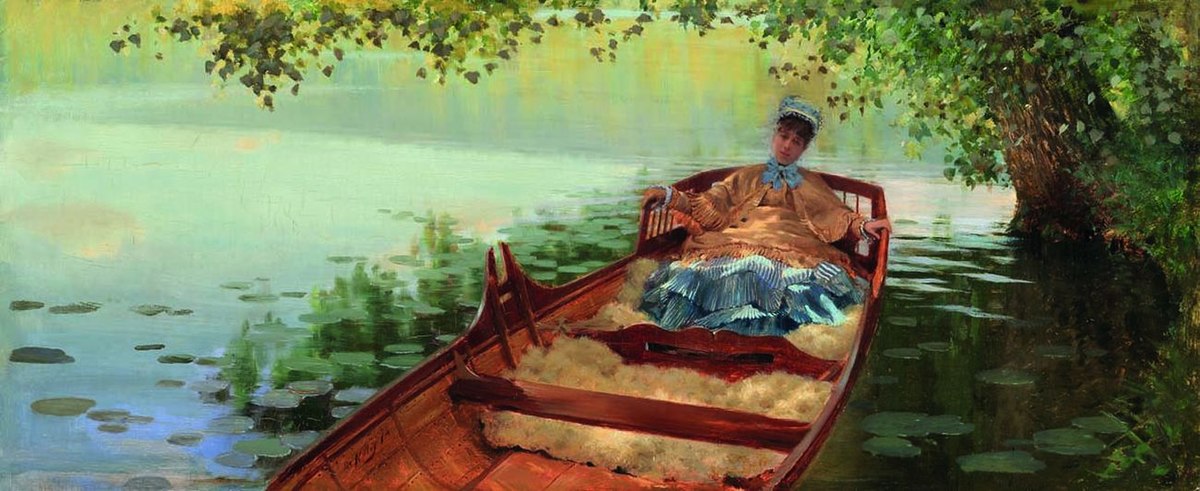

Léontine in canotto/ Léontine in a rowing boat (1874), oil on panel, 24×54 cm, Private collection.

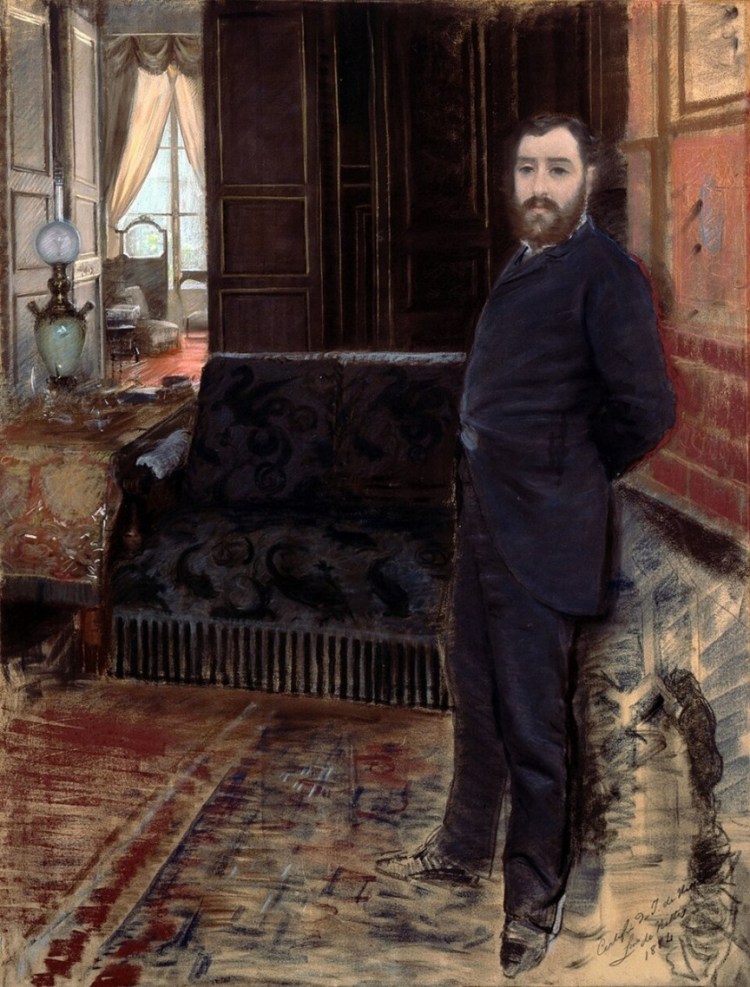

Self-Portrait (ca.1883) Pastel on canvas, 114×88 cm, Palazzo della Marra, Barletta.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

Giuseppe De Nittis: “A happy man who would have wished everyone around him to be equally happy.” Jeanne Mairet, Souvenirs, 1907.

De Nittis was a cosmopolitan artist, at ease in different social circles, open to new perspectives, and adaptable to life in foreign countries. He was socially generous and determined to succeed, qualities that made him appear warm-hearted, as Jeanne Mairet observed. And yet, like many artists of his generation, his life was far from easy.

Giuseppe Gaetano De Nittis was born on 25 February 1846 in Barletta, Italy, at Via della Cordoneria 23, now Corso Vittorio Emanuele 23. He died at the age of 38 on 21 August 1884 in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, a suburb of Paris, from what was then officially termed a “cerebral and pulmonary congestion”. The precise modern diagnosis cannot be established with certainty, but he had been suffering from serious bronchitis, and his sudden death is most plausibly understood as the result of a catastrophic stroke.

His father, Raffaele, was a liberal who supported constitutional government and national unification in opposition to the monarchy. He was arrested and imprisoned under Ferdinand II for his political views and released only after the 1848 revolution. During his imprisonment, Raffaele’s mental health declined, and in 1856 he took his own life.

The year before his death, Giuseppe also lost his brother Vincenzo to suicide, most likely prompted by financial and emotional difficulties. On 30 April of the same year, he lost his dear friend Édouard Manet, someone with whom he had just been renewing his friendship. He and his wife, Léontine Lucile Gruvelle, suffered the deaths of two children in infancy, Thérèse Lucile Joséphine and Raffaele Gaetano, who both died within months of their births in 1870 and 1872. Their third child, Jacques De Nittis, was born in Herculaneum, near Naples, in 1872 and lived until 1907.

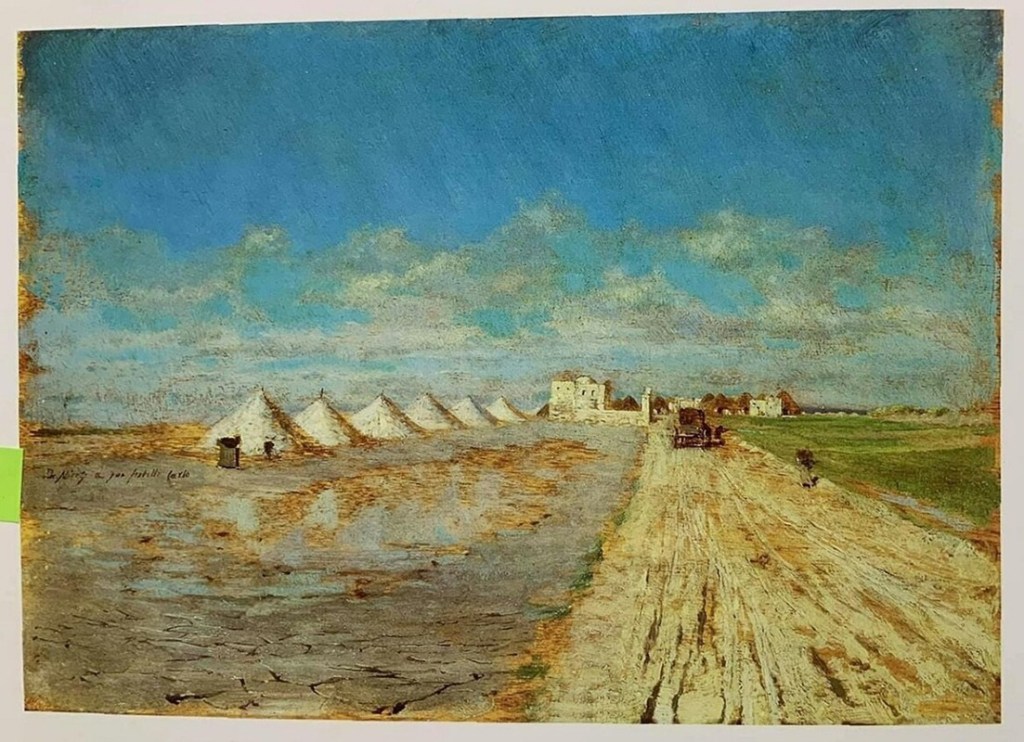

Despite the absence and early loss of their father, the orphaned brothers were lovingly raised by their paternal grandparents, as Giuseppe De Nittis recalls in his notebook, the Taccuino. He remembers the generous-hearted nature of both his grandfather and grandmother. Their grandfather had been a kind and forbearing state administrator, serving as the Architect of the Saltworks of Barletta and opening his home to workers whose thatched cottages had caught fire.

Le saline di Salina di Barletta/The Saltworks of Barletta (1864), oil on canvas 18 × 24 cm, Private collection.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

After Raffaele’s death in 1856, the eldest brother took responsibility for the family’s affairs. In 1860, Vincenzo moved with the family to Naples to improve their prospects. Although he initially opposed Giuseppe’s desire to become a painter, he eventually consented to his brother’s wishes.

Despite the fragile emotional circumstances of his youth, De Nittis’s art rarely addresses themes of social injustice or the suffering of the poor and marginalised. This is not to suggest that he was socially aloof or insensitive, or that he never included working men or women in his art. In 1879, he painted a scene in Posillipo featuring three working women, titled Au Revoir!, and in the same year he exhibited La venditrice di fiammiferi a Londra/ The Match-girl in London in Paris, although it is difficult to locate an image of the latter.

Au revoir (1879), oil on canvas, 36×54.5 cm, Private collection.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

Earlier, his Sur la route de Castellamare/ On the Road to Castellamare (1875) depicts a similarly popular scene, composed around a road, as in the more famous works The Road to Brindisi and Crossing the Apennines. The painting captures an intensely hot day, showing sunburned workers pausing from their labour: one eats grapes while another has removed his workboots. The baskets carried by the man on the left will soon be loaded onto the nearby donkey and filled with stones. While these figures are clearly labourers exposed to some hardship, De Nittis does not present them as exhausted, vulnerable, or exploited.

Sur la route de Castellammare/On the road to Castellammare (1875), oil on canvas,

54.5×74.5 cm, Private collection.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

This neutral tone is particularly evident when compared with Bestie da Soma/ Beasts of Burden, painted by Teofilo Patini in 1886. Patini, born in Castel del Sangro in the province of L’Aquila and also trained in Naples at the Accademia, sought to convey a clear socialist message. His workers are shown in states of poverty and hardship, expressed through their posture, facial expressions, and the composition of the work. By contrast, De Nittis occasionally drew on popular figures to introduce a moderate sense of realism into his landscapes and cityscapes, but he was not a campaigner for social justice.

Teofilo Patini: Bestie da soma/ Beasts of Burden (1886), oil on canvas, 244 × 416 cm, Palazzo del Governo, L’Aquila.

(Credit: Wikipedia).

For the most part, his subjects were rooted in bourgeois urban life, or were painted landscapes. Such choices were likely both practical (commercial), and aesthetic, yet we also know that his visits to London exposed him to scenes of poverty that left a mark. An account by Jules Claretie recalls how he passed through the poor areas of London, such as Whitechapel, in the company of De Nittis, encountering a world of neglect, poor lodgings, workhouses, and shoeless paupers. Moreover, in the Taccuino, De Nittis recalls Rotten Row, where people not favoured by fortune, wealth, or privilege seemed to be “nothing but a fleeting moment, a nonentity crushed under the wheels of the carriages.”

The biographical and autobiographical accounts of De Nittis’s life present a story of hard work, social success, and public recognition. But the reputation he won as a painter required diligence, flexibility, and self-determined assertion. He achieved the fame and recognition he deserved, yet, as Degas noted in a letter to Léontine, “He was happy and understood by the world, but not for long.” It was the determination and foresight of Léontine that ensured that a large part of his artistic legacy was collated and preserved in Barletta.

Léontine left her collection of her husband’s works to Barletta in her 1912 will, and after her death in 1913 the collection arrived in the city in March 1914. It was first housed in the former Dominican convent and then moved through a series of provisional municipal spaces before being gathered into a more formal museum setting by 1929. During the Second World War it was evacuated to Castel del Monte for safety, and afterwards returned to the city, where conditions again proved insufficient. In 1992 the works were transferred to the Castello Svevo, which offered improved but still limited accommodation. The collection finally found a stable and appropriate home in Palazzo della Marra, where it was inaugurated in March 2007.

Palazzo della Marra, Barletta. (Credit: Wikipedia).

In 1993, Federico Zeri was in an interview about De Nittis, conducted by Enzo del Vecchio, for the RAI. Zeri (1921–1998) was an Italian art historian renowned for his exceptional eye, his sharp connoisseurship, and his ability to combine meticulous archival work with intuitive stylistic insight. At this point, the collection was still in the Castello Svevo, and Zeri’s praise was placed in the context of the necessity for De Nittis’s recognition, both intellectually and through his work being granted a worthy location.

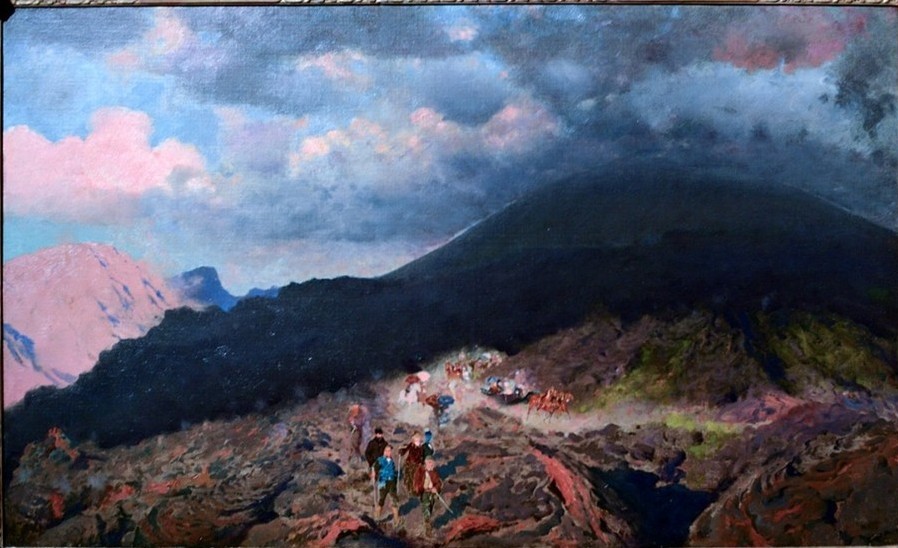

In a brief interview, he captures the sense of De Nittis as a painter with an acute vision and the skill to express that vision. He is seen as not just a great Impressionist (or member of any particular group) but as a great painter in absolute terms. He is recognised for his capacity to learn from the artistic circles around him and to adapt and capture what he sees. Zeri points out his skill in rendering the pristine, muffled sensation of a fresh snowfall. He also states that in La discesa dal Vesuvio/ The Descent from Vesuvius, De Nittis demonstrates his mastery by showing figures backlit by an atmospheric Neapolitan sunset.

Eruzione del Vesuvio (figure che discendono il Vesuvio in eruzione)/ The Eruption of Vesuvius (1872), oil on canvas, 71×130 cm, Palazzo della Marra, Barletta.

(Credit: Catalogo generale dei Beni Culturali).

Zeri justly describes him as a painter capable of capturing both the bright beams of Neapolitan light and the foggy, misty atmospheres of Paris or London. According to Zeri, he also possesses an extraordinary talent for framing his scenes with the eye of a photographer. He is capable of daring choices, such as filling much of a canvas with a preponderance of sky, or, I would add, of road.

In looking at De Nittis’s work Nei campi intorno a Londra/ In the Fields Around London (ca.1875) a very French-looking scene, Zeri suggests that at this moment De Nittis appears to be a kind of home-grown Sisley or Pissarro.

Nei campi intorno a Londra/ In the fields around London (1875), oil on canvas, 45×55 cm, Private collection.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

This observation again draws out his versatility as a painter, as well as his willingness to learn from what he saw around him. We could add one more citation to Zeri’s anecdotal list, Monet’s Poppy Field near Argenteuil/ Les Coquelicots (1873).

Claude Monet: Les Coquelicots/ Poppy Field near Argenteuil (1873), oil on canvas, 50×65.3cm, Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

De Nittis was highly respected in Paris during his lifetime, where he was seen as both an endearing outsider and an honorary Parisian. He was a painter in demand, and while he said that his fortune was made in Paris, he also acknowledged the support he received in London from the wealthy British banker Kaye Knowles. Praise for the artist was widespread during his lifetime. In one of his letters, edited by Victor Merlhès, Gauguin asserted that ‘Everyone copies either De Nittis or the great Bastien-Lepage. De Nittis and Lepage achieved perfection in what the Impressionists started.’

A number of Italian landscape painters had established reputations in France before De Nittis. Gabriele Smargiassi, for example, resided in Paris from 1828 to 1837, working on commission for Queen Maria Amalia, a Bourbon princess of the Two Sicilies who had been raised in the cosmopolitan Neapolitan court. Smargiassi produced landscapes of Naples, Rome, and France for the queen, and also exhibited at the Salon.

During De Nittis’s early years in the City of Light, Giuseppe Palizzi (1812–1888) had already established himself as a well-connected intermediary between Paris and Italy. He had met members of the Barbizon School and exhibited regularly at the Salon.

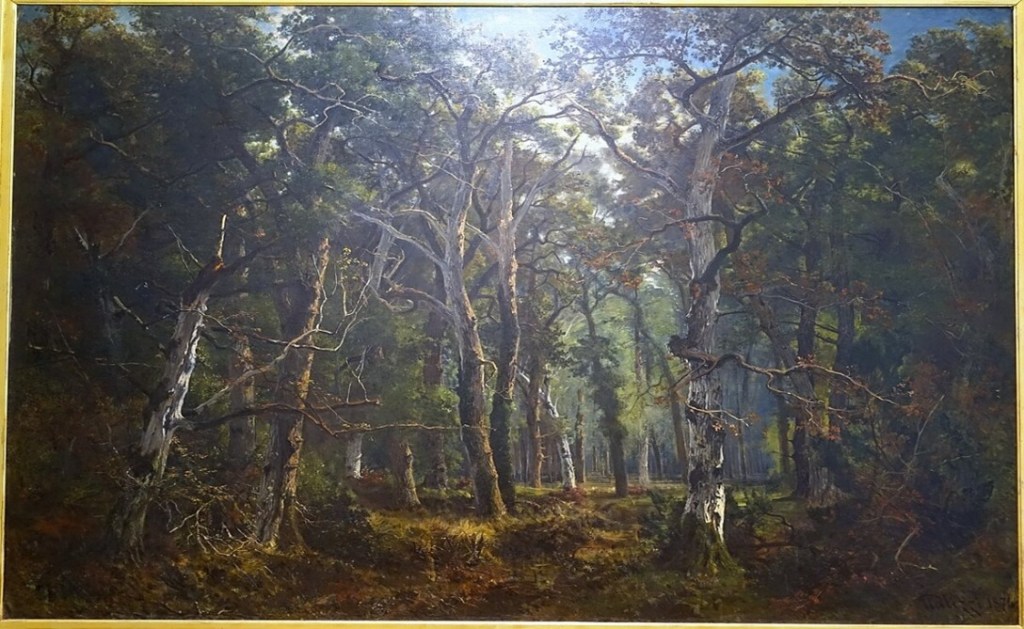

Gabriele Smargiassi: Paesaggio napoletano/ Neapolitan Landscape (1830), 30 x 40 cm, Private collection and Giuseppe Palizzi: Bosco di Fontainebleau/Forest of Fontainebleau (1874),oil on canvas, 232×320 cm, GNAM, Roma.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

It was Palizzi who introduced the Florentine Macchiaioli to Barbizon works and the plein air painting tradition. As well as being part of the Neapolitan School of Resina, De Nittis met Giovanni Fattori in Florence. The latter also had a mutual friend in Degas – as suggested by the fact that the two artists exchanged portraits in 1860.

Giovanni Fattori: La libacciata/ The Southwesterly Wind (1880-1885), oil on panel, 28.4x68cm, palazzo Pitti, Galleria d’arte moderna, Firenze.

(Credit: Wikipedia).

By 1868, the art dealer Goupil was asking De Nittis to recommend Italian artists, suggesting that he had assumed a mediating role in Paris previously occupied by Palizzi. It was at the Universal Exposition of 1867 that French critics began to recognise the quality and potential of Italian art as a contributor to contemporary culture. At the Salon of that year, Domenico Morelli won a silver medal for painting and was exploring a looser manner of handling, characterised by fluid brushwork and an increasing emphasis on immediate visual impressions. At the same time, artists associated with the School of Resina were engaged in a sustained investigation of light.

Considered collectively, many Italian painters formed an important component of a broader movement towards a modern, perceptually grounded style, one concerned with macchia, chiaroscuro, light, sensation, and the desire to capture the immediacy of lived experience.

Further evidence of cultural exchange is found in the fact that Florence held some significant collections of French art: the collections of Marie-Caroline, Duchess of Berry and Prince Anatoly Demidov offered insight into French taste. The collections held works of neoclassical restraint and Romantic sensibility. The Marquis Marcellin Desboutin, a printmaker who was a friend of both Degas and De Nittis had a Florentine villa which brought together French and Italian cultural figures who were passing through. His villa L’Ombrellino on the hill of Bellosguardo was referred to as the ‘Parisian circle on the Arno.’

Edouard Manet: L’Artiste, Portrait de Marcellin Desboutin/ The Artist, Portrait of Marcellin Desboutin (1875), oil on canvas, 195.5×131.5 cm, Museu de Arte de São Paulo.

(Cedit: Wikimedia Commons).

So, De Nittis was part of the French artistic scene, the cosmopolitan gatherings in Florence and he also had a brief spell in the Accademia di Belle Arti in Naples, followed by a deeper and sustained connection with the artists of The School of Resina.

He was open to the innovations of his time; he exhibited at the first impressionist exhibition of 1874, encouraged by Degas to lend weight to the new movement. He also had a significant collection of impressionist paintings, which were purchased with the discerning help of Caillebotte. Nonetheless, he did not exhibit his works with the Impressionists again and he negotiated his own path between modern innovation and the demands of the market.

In contrast to his rebellious and independent attitude towards the teaching offered at the Accademia in Naples, De Nittis seemed to make the most of, and take the best from, the opportunities that came his way. He was even attentive to the style of Meissonier when he first came to Paris though, as he later admitted, this did not really suit him. We could also set him beside James Tissot and Alfred Stevens, if we make our criteria for comparison broad enough.

He was, for the most part, incorporating the innovations of Manet and the Impressionists into a style that remained accessible to a broader public. Like his friend Manet, he continued to exhibit at the Salon and did not alienate himself from the establishment. To label his work as belonging to the juste milieu is therefore not entirely unfair: he occupied a position between a carefully finished realism suited to the Salon public and a painterly style aligned with experimental modernism.

In several of his most acclaimed works he attends closely to Parisian fashion, though never in the explicit, fashion-plate idiom familiar from Alfred Stevens or James Tissot. His elegantly dressed figures are typically shown in motion, crossing urban spaces that are equally studies in atmosphere and modern architecture. The result is a subtly balanced image in which clothing, light, and the city’s fabric coexist without hierarchy. These scenes remain indebted to the Neapolitan landscape tradition, whose clarity of light and sense of spatial breadth continue to inform his Parisian views. Even the city’s distinctive architecture, while clearly referenced, is never allowed to dominate in a self-conscious or jingoistic way. La Place de la Concorde provides a telling example: the recognisable setting is held within a veil of atmospheric effects, and its passing figures animate the square without turning it into a piece of obvious civic rhetoric.

Two of De Nittis’s early landscapes, painted in 1866, when he was engaged with the School of Resina, Casale nei dintorni di Napoli and L’Ofantino share stylistic characteristics. They are both charged with scrupulously realised details and both have blue skies that evoke the effect of enamel.

Casale nei dintorni di Napoli/ Farmhouse near Naples (1866), oil on canvas, 43×75 cm, Museo di Capodimonte, Napoli. L’Ofantino/ On the Ofantino channel (1866), oil on canvas, 60×100 cm, Private collection.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

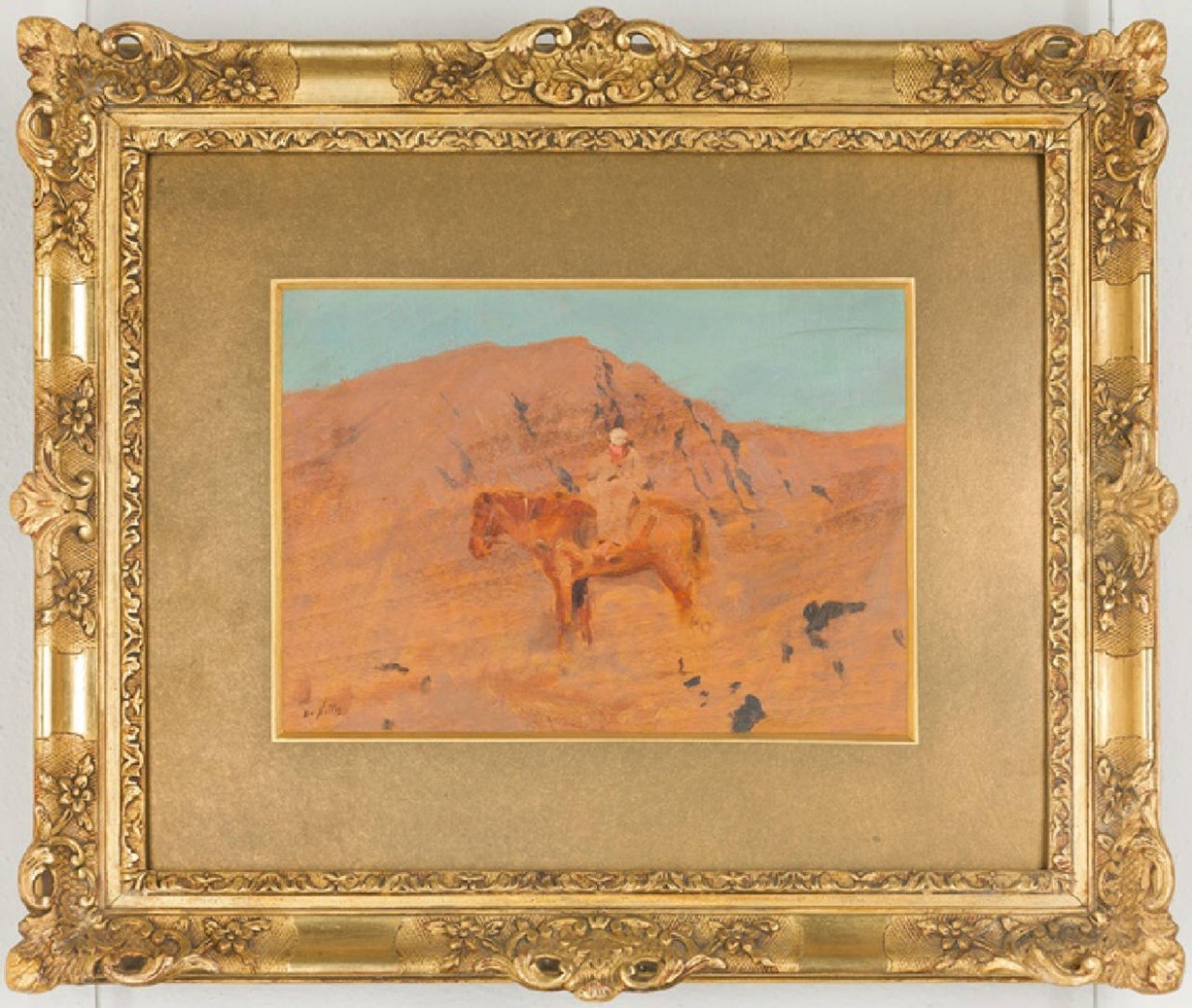

When he later returned to Naples and Barletta he demonstrated a different style of landscape painting. Most notably, his plein air studies of Vesuvius Sulle falde del Vesuvius/ On the Slopes of Vesuvius revealed a dramatically modern style of landscape with a radically simplified form and chromatic range. In the rare moments when figures occupy these landscapes they are barely visible and seem to threaten to dissolve into the geological background. Goupil informed him that dal vero studies of such radical character were unlikely to be well received by the public and, on that basis, declined to accept them. De Nittis went on to sell some of these works privately in London.

Paesaggio Vesuviano/ Vesuvian Landscape (1871-2), Oil on panel, 18.5 x 31.7 cm, Private collection.

(Credit: Daxer and Marschall).

Sulle falde del Vesuvio/ On the Slopes of Vesuvius (1872), oil on panel, Galleria d’Arte Moderna di Milano.

(Credit: Catalogo generale dei Beni Culturali).

Pioggia di cenere/ The Rain of Ashes (1872), oil on canvas, 40.5x28cm, Galleria d’Arte Moderna Florence.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

With the eruption of 26 April 1872, De Nittis was able to produce works which combined natural study with human drama. La pioggia di cenere depicts the people of Resina fleeing the eruption in a reportage-like canvas. The figures are dwarfed by overwhelming natural forces. There are also two studies of the eruption (one already illustrated above) that have smaller groups of people, horses and a carriage descending from Vesuvius in bright pools of light permitted by gaps in the clouds of ash. Here too the people are dynamic but small compared to the might of the volcano and its effects.

L’eruzione del Vesuvio/ The eruption of Mount Vesuvius – II (1872), oil on canvas, Private collection.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

Together with Degas and Zandomeneghi, he created a freer and more direct pastel style. The favoured medium of Rosalba and Liotard was reaffirmed as serving the desire to capture the moment. Pastel drawing creates a rich, lustrous, and realistic effect by depositing pure, highly pigmented particles onto the surface, allowing colour to sit on the paper as a velvety, light-catching layer rather than sinking in. With no drying time and no preparatory medium, it has the advantage of immediacy and it can be used to create either finely finished works, or works that excitingly hover between the status of a sketch and a complete picture. From 1876, De Nittis wanted to produce large pastel works, of a natural size and scale. His Portrait d’Edmond de Goncourt, Le corse al Bois de Boulogne and La femme aux pompons offer examples from 1879-1881.

Portrait d’Edmond de Goncourt (1881), pastel on paper, 87 × 115 cm, Nancy Municipal Archives (Académie Goncourt deposit).

(Credit: ‘De Nittis – At the Salon’).

The Portrait of Edmond de Goncourt 1881 depicts the famous diarist, novelist, and critic who played a significant role in shaping late nineteenth-century literary taste. Goncourt cultivated a distinctly aesthetic, hyper-observant, and socially attuned prose style. In his diaries and fiction, he often turned his attention toward figures on the social margins, such as prostitutes, servants, minor artists, and other lives overlooked by bourgeois convention, recording them with a mixture of curiosity, acuity, and froideur. Here De Nittis works the pigment into a dense surface, creating an intensely real and tactile finish. The delight in using white and cream for fabrics, paper, and a snowy exterior is also evident. The level of detail is masterful, with a fine realisation of book spines, table objects, furnishings, as well as the rendering of Goncourt’s hair, jacket, and the curtains.

Le corse al Bois de Boulogne/ Le corse a Auteuil (1881), pastel on canvas, 200 × 395 cm, GNAM, Roma.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

Alle Course de Auteil (At the Races of Auteil) 1881, our second large pastel work, is a secular triptych of modern life in Paris. This combination of three segments of racecourse life simultaneously offers three studies in intensely photographic framing, as well as some radical viewpoints from different levels and locations. It is not the sport that is depicted here but the see-and-be-seen culture of the haute bourgeoisie engaging in a leisure activity. Their elegant attire, with fine coats, hats, and dresses, reinforces the sense of display and social distinction. The composition suggests a bright autumn day, with the light and atmosphere conveying a crisp, seasonal quality.

La femme aux pompons (ca. 1879), pastel on canvas, 116.5 × 90 cm, Galleria d’Arte Moderna di Milano.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

La femme aux pompons (c. 1879) shows a young woman seated outdoors on a wooden bench, turning towards the viewer. This rich pastel work achieves a remarkable sense of texture in her clothing and skin, while also capturing fleeting atmospheric effects. There is a contrast between the careful realisation of the sitter and her attire and the more gently defined landscape around her. This study of character, costume, light and atmosphere contributes to the evolving vocabulary of modern femininity in nineteenth‑century Parisian painting.

In De Nittis’s brief but highly productive life, the year of his social affirmation, 1878, came only six years before he died. He pursued the success that would reward him and offer the acclaim that he merited. In the course of doing so he moved from the management of Reitlinger to Goupil and subsequently freed himself, contractually at least, from Goupil, although at considerable financial cost. As mentioned earlier, he also travelled to London to paint ten London scenes for Kaye Knowles. Thus, on top of the labour art and creativity, we must add the demands of travel, financial worry, and social networking. In 1878 De Nittis was at a peak. He won a first-class medal at the Salon and, at the Universal Exhibition, displayed twelve paintings to great public and critical acclaim. He was awarded the Medal of Honour and appointed to the Legion of Honour.

With his change in social standing, he decided to move to a more prestigious location; he bought a house in rue Viète at the beginning of 1880. Here he held Saturday evening soirées that were attended by many famous guests of high social standing, comprising aristocratic, literary and artistic personalities. In this new residence, De Nittis was able to display his collection of Japanese art and his Impressionist paintings, as well as offering guests an interior decoration which was at the height of fashion. Almost in the manner of literary social satire, after his passing, the widowed Léontine found that she could count on the loyalty and support of only a handful of true friends.

Petit déjeuner dans le jardin/ Breakfast in the Garden (ca.1883–1884), oil or pastel on canvas, 81 × 117 cm, Palazzo della Marra, Barletta.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

Among the artist’s last works, there are scenes of close family moments, portrayed in a garden in Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Breakfast in the Garden and three studies entitled In the Hammock reveal two fundamental characteristics: they mark both a ‘prolonged observation of reality’ and ‘an emotional testament to his beloved family,’ as Renato Miracco has observed. The empty chair in the breakfast scene (a scene realised in scrupulous detail with wonderful still-life studies within it) adds a note of self-referential realism, as it documents the absence of the artist from the table, while he works on the painting. At the same time, the absence now holds a sense of poignancy, as we know that he was to die not long after the work’s completion. In the Hammock III also conveys another visual emotion in this tranquil garden setting; the closeness of Léontine and Jacques.

In the Hammock – III / Dans le hamac III (1884), oil on canvas, 65 × 42 cm, Museo Frugone, Genova.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

Pranzo a Posillipo (c. 1879) takes us back in time a little, yet it unites a number of elements and offers an exquisite image for consideration. The picture conveys visual emotions of warmth and conviviality in an iconic Neapolitan setting. This unfinished work shows a debt to the work of Manet, and, as Martelli observed, it is as if a café-chantant scene had been transposed to Naples. The painting connects with a fond memory recorded in the Taccuino, in which De Nittis describes gatherings on a terrace beneath a full moon. We are drawn to the figure of Léontine, her head inclined in a gesture of recognition. Beyond her lie Capo Posillipo and Palazzo Donn’Anna, with the soft, glassy light of the sea and the beautifully realised colours of an evening sky in the distance. There is tremendous warmth in this image, coupled with a slightly wistful and valedictory mood, capturing a passing moment at sunset.

Lunch at Posillipo/ Pranzo a Posillipo (1879), oil on canvas, 111×173.3 cm, Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Milano.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

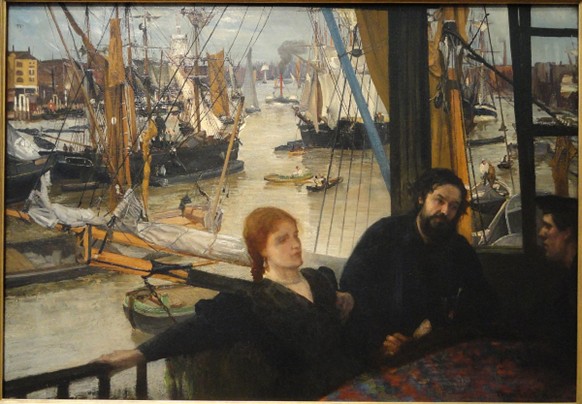

There is something inherently mesmerising about the prospect of a dining scene at the water’s edge. A similar contrast between close company and open water is captured in Whistler’s Wapping (1860–1864), which features the artist’s model and partner Joanna Hiffernan reclining on the balcony rail of a Thames-side pub, the Angel, in Cherry Gardens, Bermondsey. The scene here is more urban and socially realistic: we are in the working-class docklands of the Thames rather than the gulf of Naples. Yet both works seem to function as existential tableaux, placing human interaction at the edge of an open expanse of water.

James McNeill Whistler: Wapping on the Thames (1860–1864),oil on canvas, 72×108 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C..

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

The sense of suspended, heightened emotional significance that such a setting creates is also exploited by Bergman in the lakeside scene from Wild Strawberries (Smultronstället), as if Nature herself is timelessly observing the gathering. Lake Vättern seems to pose a silent question as the professor, the young travellers, and Marianne sit together in tenuous harmony. Arguably, it complements an existential yearning expressed by the actors in the Swedish hymn-poem by Johan Olof Wallin (1779–1839): ‘Where is the friend I seek wherever I go?’ (‘Var är den vän som överallt jag söker?’)

A scene from Ingmar Bergman’s Wild Strawberries (Smultronstället) of 1957.

(Credit: Musings on Films).

Pranzo a Posillipo can therefore be seen as a miniature dramatic form which combines warmth with a soft undertone of transience. As such, it works well as a conclusion to our synoptic and biographical reflection on the work of De Nittis. From here we can gain some sense of his artistic range, by giving individual consideration to a number of his paintings.

De Nittis – a selection of works.

La traversata degli Appennini / The Crossing of the Appennines (1867).

La traversata degli Appennini (Crossing the Apennines), oil on canvas, 45×76.5 cm, Museo di Capodimonte, Naples.

In this work, the road is the clear protagonist. The scene is overcast and veiled in mist or haze, and the sober tones and muted colours evoke a mood of melancholy, nostalgia, or introspection. The dampness of the setting is emphasised by the multiple cart tracks marking the road. There is a strong sense of departure: leaving one world behind, perhaps moving toward the unknown. Compositions featuring roads were a recurring motif in De Nittis’s repertoire, and this painting was followed by his famous, brighter work, La strada da Napoli a Brindisi / The Road from Naples to Brindisi (1872).

La strada da Napoli a Brindisi / The Road from Naples to Brindisi (1872), oil on canvas, 27×52 cm, Indianapolis Museum of Art.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

The Return from the Ball/ Il Ritorno dal Ballo (1870).

Il ritorno dal ballo/ Returning from the Ball (1870), oil on panel, 24 × 30.5 cm, Private collection.

This work reflects the concerns of the art merchant Goupil, who encouraged De Nittis towards producing Salon-friendly and commercially astute paintings. Among the subjects promoted were scenes such as this, featuring figures sensually attired in costumes suggestive of the ancien régime. This relatively small oil painting (24 × 16.5 cm) carries vaguely aristocratic overtones and evokes a sense of refined sociability, perhaps offering a sanitised or fantasy vision of pre-revolutionary France.

However, the narrative ambiguity of the scene feels distinctly modern. Set in a threshold space, the painting shows elegant but undefined women looking back through a garden gateway, suggesting the moment after a social event. While they appear cognisant of some shared activity, its nature remains unclear; and although they represent the height of elegance, their faces are withheld from view. Edoardo Dalbono’s watercolour Adelina ed Eleonora of 1873 seems consonant with the mood created by De Nittis and I add it here as an interesting juxtaposition.

From the Top of the Diligence (Stagecoach) / Dall’alto della diligenza (1872).

Dall’alto della diligenza/ From the Top of the Stagecoach (ca.1872-1875), oil on panel, 26.5×36.5, Private collection.

(Credit: WikiArt).

The viewer shares the painter’s viewpoint from the top of the coach, which invites participation in the scene while also creating a sense of detachment and observation. This elevated perspective suggests movement, with the bright road ahead of the coach dominating the foreground, at the cost of human detail. The composition is sparsely inhabited, creating an overall feeling of distance and openness. There is an atmospheric restraint, with attention focused on light and the dirt road rather than narrative incident. Seen from a position of transit rather than rootedness, the landscape can be read as a realistic document, or a visual metaphor for the journeys and transitions of life.

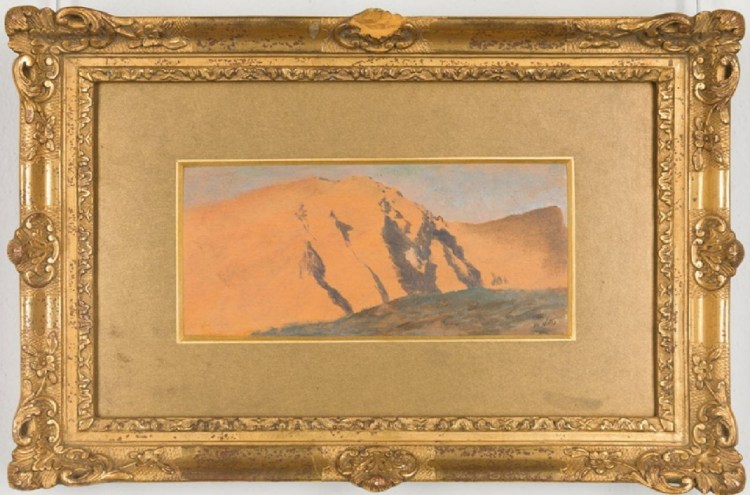

Sulle falde di Vesuvius / On the Slopes of Vesuvius (1872).

This title refers to a series of plein air studies of Vesuvius from 1872, of which an indicative example is provided here. These works were executed from direct observation, dal vero, and are not in the manner of Grand Tour souvenirs. Rather, they are careful studies that record Vesuvius under varying light conditions. They are almost geological in character, depicting crevasses, ridges, and the rocky slopes, with only sparse vegetation.

De Nittis employs Naples yellow for the first time in these works. They are presented in close-up, without a panoramic view, and appear to be exercises in formal simplification and concentrated focus. As noted above, in the rare instances where human figures appear, they are almost entirely absorbed into the landscape, so pronounced is the degree of abstraction.

Sulle falde del Vesuvio/ On the Slopes of Vesuvius (1872), oil on panel, 13×18 cm, Galleria d’Arte Moderna di Milano.

(Credit: Catalogo generale dei Beni Culturali).

Che Freddo!/ Fait il Froid! (1874) and Sulla neve/ On the Snowy Path (1875).

Fait il froid/ Che freddo! (1874), oil on canvas, 43 × 32.5 cm, Private collection.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

Sulla neve/ On the snowy path (1875), oil on canvas, 43 × 32.5 cm, Private collection.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

The heavy snowfall in the winter of 1874–1875 offered De Nittis the opportunity to make numerous studies of winter skies and snowy scenes. The profound silence of the snow, the pale winter light, and the outstretched, empty expanses of white delighted him, as he reflected in a passage in his Taccuino. He was so captivated by the beautifully “Japanese” vision it created that he declared it brought him fully into his own element and confirmed the vocation for which he was born: “to paint, to admire, to dream.”

These works constituted a significant and innovative departure for De Nittis in his study of atmospheric light, his use of contrast, and his employment of cool tones such as white, grey, beige, and violet. Che Freddo! was presented at the 1874 Salon, where it was well received by the public; it was subsequently sold by Goupil to an American collector for the considerable sum of 10,000 francs. In compositional terms, the framing is radical and engages the imagination in reconstructing a realistic image with a subtle narrative component. The women featured crossing a wide pathway, beside an arcing cart track, are fashionably dressed in dark costumes, and also convey a sense of rapid movement in the cold. This dynamism is counterbalanced as one of the women is being pulled back in a different direction by a child, who appears momentarily distracted. The cart track creates a depth of field that draws the eye toward a dark carriage, which contrasts with the snowy weather. In the background, an atmospheric setting stretches upward into a beautifully realised winter sky.

Sulla Neve takes the Impressionist theme of social leisure and modern life and places it in an informal, quiet setting. A woman is walking her two dogs, offering a study of movement and exuberance on a winter’s day against an architectural backdrop. Once more, we see De Nittis’s mastery of the crisp, reflective quality of winter light on snow and its interactions with different surfaces, shadows, and figures. Particularly striking is the contrast between the trodden snow and the untouched, soft, powdery expanses, which suggest a profound sense of silence.

Parisians of the Place de la Concorde (c.1875)/ Parisiens de la Place de la Concorde, A Corner of the Place de la Concorde (1880)/ Un coin de la Place de la Concorde.

La Place de la Concorde (1875), a photogravure; the original is part of the collection at the Presidential Atatürk Museum Mansion in Ankara, Turkey.

(Credit: Rob Zanger, Rare Books).

A Corner of the Place de la Concorde in Paris/ Un Coin de la Place de la Concorde (1880), oil on canvas, 65 × 81 cm, private collection.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

The first of these two works, for which I can only find a photogravure reproduction, depicts a rainy day in dark tones, with a reflective pavement. In contrast, A Corner of the Place de la Concorde presents the setting in a brighter, clearer and more sharply defined moment. The 1875 work was widely disseminated in reproductions, such as the illustration used here, and may well have been a source of inspiration for a number of subsequent painters of boulevard scenes, including Jean Béraud (1849–1935).

While remaining in the realm of probability, Boldini’s Place de Clichy (1874) is often credited with encouraging De Nittis away from narrative vignettes such as Fait-il froid! towards a broader urban vision. What is certain is that La Place de la Concorde attracted considerable attention after its exhibition at the Salon of 1875, and it was sold in October of that year to the Sultan of Turkey for 25,000 francs.

As mentioned in passing earlier, Parisians of the Place de la Concorde (1875) chooses a location dense with buildings and monuments that speak of Parisian history, French colonial ambition, administrative authority and social prestige. These include the Luxor Obelisk, the Hôtel de Crillon, the Hôtel de la Marine, the Église de la Madeleine and the Fontaines de la Concorde. Yet all of these are embedded within a self-consciously modern vision of life as mutable and provisional. The protean nature of modern experience and perception is further emphasised in A Corner of the Place de la Concorde (1880), which alters the distance, angle and atmosphere of the same location. It is as if the easel (or metaphorical viewfinder) has been repositioned on a different day. This later work adopts a wider angle and does not include a principal figural group shown from behind. It also features that familiar expanse of empty ground typical of De Nittis, here reflecting a brighter light. The figures, the atmosphere and the composition are all tuned to a lighter register.

Westminster (c.1875).

Westminster (ca. 1875), oil on canvas, 110 × 192 cm, private collection.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

Kaye Knowles, the British banker and member of the country’s economic and social elite, gave De Nittis the opportunity to explore London’s distinctive visual and social character. In this work, fog or smog dissolves the mass of the Palace of Westminster in a manner that aligns with the atmospheric studies of London produced by Whistler in some of his Nocturnes, and by Monet in his studies of the city of 1870–1871. De Nittis, however, restrains his level of abstraction, and the Parliament building remains clearly recognisable.

The beauty of the image contains an inherent irony and ambivalence. The grand architecture is veiled by a haze intensified by coal consumption and industrialisation. There is a further irony in the fact that Knowles’s family wealth had its origins in the Lancashire coal-mining industry. This is not to suggest that De Nittis was making a deliberate social statement, but it is something that cannot be overlooked when viewing the work today. Despite its atmospheric origins in industrial pollution, the image is delicate, beautiful and bound to a particular moment.

Once more, De Nittis uses a bridge as the staging point for his view, enabling him to animate the cityscape with recognisable urban types. The unheroic Londoner, casually smoking on the bridge, balances the grandeur of the Houses of Parliament and adds an air of realism, while stopping short of overt social comment or critique.

There is something dignified and muted about the painting. It is not merely northern greyness; rather, it possesses a compelling sense of mystery. When we recall De Nittis’s remarks on the shocking poverty of London, we see that he nevertheless remained open to finding beauty and authenticity in diverse landscapes and atmospheric conditions. His paintings narrate the streets of London in a manner that is both modern and ‘reliable’, a quality that may have appealed to British critics.

Returning from the Races/ Retour des courses (1875).

Return from the Races/ Ritorno dalle corse (1875), oil on canvas, 32.5 × 43 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

The fascination of this composition lies in its organisation around the spectator’s gaze, giving the impression that we are walking into the scene and momentarily glimpsing frozen time. I find it interesting to compare the work with another famous preceding outdoor social tableau, albeit in a different context, Manet’s Le Concert aux Tuileries (1862). The contrasts somehow add weight to De Nittis’s chosen style.

Édouard Manet: Le Concert aux Tuileries/ Music in the Tuileries (1862), Oil on Canvas, 76×118 cm, The National Gallery, London.

(Credit: Wikipedia).

Both works share a fascination with modern social life, capturing fleeting moments of public leisure and observation. In both works, the spectator is drawn into the scene, positioned as a participant in the unfolding event, at the racecourse or amidst a fashionable concert. Manet flattens the pictorial plane, creating a tapestry-like surface in which figures and space coexist with minimal depth, while De Nittis employs an angled composition that guides the eye through the scene, producing a more immersive, almost cinematic effect. Both artists focus on the rhythm of the crowd and the subtleties of posture, gesture and attire, yet they achieve different atmospheric outcomes. Manet’s even lighting emphasizes pattern and surface, whereas De Nittis modulates natural light to animate space and movement. Together, the works resonate as parallel experiments in portraying modernity, one emphasizing the flat, social mosaic of the urban crowd, the other the dynamic, perspectival interplay of leisure, observation and the spectator’s gaze.

The Bridge / Ponte (1876).

Il Ponte/ The Bridge (ca. 1876), oil on canvas, 54×74 cm, Palazzo della Marra, Barletta.

(Credit: Artsupp).

When the viewer registers the head of a small girl at the base of the composition, they become aware of the audacious nature of the framing. It seems highly likely that De Nittis used the boundaries of the window of his mobile atelier-cab to shape this view. The painting balances realism with an Impressionist sensibility. The river is presented as an urban experience, in which infrastructure, bridges, and modes of transit convey the energy of the modern city. At the same time, De Nittis’s landscape skills come into play, lending the work an atmospheric rendering that tempers this modernity with tonal restraint.

Boulevard Haussmann (I and II) (1877).

Boulevard Haussman I (1877), watercolour on card, 31×41 cm, Private collection.

(Credit: Artnet).

These watercolours (only the first illustrated here), exhibited by De Nittis at the Paris Salon of 1877, were deemed unparalleled masterpieces by Degas. The medium lends the works a sense of lightness and immediacy, and the brief glimpse of Parisian life offers a cosmopolitan view: a cultural stage marked by mobility, anonymity, and mixture. There is delight in the study of light effects and contrasts, in the use of realistic depth-of-field, and in figures suggested with a delicate, blurred, fleeting touch that conveys motion.

The Japanese Screen / Paravento giapponese (1878).

Il paravento giapponese/ The Japanese folding screen (ca.1878), watercolor on paper, 22.5 × 31.5 cm, Pinacoteca Metropolitana di Bari.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

This work from the gallery of Bari illustrates the importance of Japanese culture for De Nittis, reflected in his interest in prints as well as decorative and material objects. The screen in the painting serves both a decorative and a compositional purpose. Its decoration, along with that of the room as a whole, is executed with restraint and subtly marked by Japanese motifs. Compositionally, the screen provides a linear and angular contrast that draws attention to the woman’s relaxed, sinuous pose.

This is an intimate work set within a private domestic interior, adopting a muted and harmonious palette. Works such as this underscore De Nittis’s status as a modern, cosmopolitan figure, fully attuned to the vogue for Japonisme and the forms of inspiration it could offer.

La parfumerie Violet, à l’angle du Boulevard des Capucines et de la rue Scribe (The Violet Perfumery) c. 1880

La parfumerie Violet/ Profumeria Violet (1882), oil on canvas, 74 × 62 cm, Musée Carnavalet, Paris.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

This painting offers a testimony to the emerging dialogue between photography and painting that unfolded in the second half of the nineteenth century. A number of tropes later associated with early twentieth-century street photography are visible here: reflections layered over interior space, and the shared transience and anonymity of passing figures. The Perfumery is emblematic of Parisian elegance, luxury goods, female consumption, and the theatricality of shopping. The purchasers are both spectators and performers.

The brisk painting techniques used to render the strolling women and men make them types rather than caricatures. De Nittis places us in the role of witnesses without offering a critique, giving the scene a lucid ephemerality.

This is the Paris of pavements, tailored coats, and polished surfaces: a world rendered in a sober steel-blue palette that recalls the works of Caillebotte. The darker tonality highlights the contrasts of white and silver in the shop windows, as well as the splashes of white fabrics and objects, which punctuate the composition like pin-pricks of light.

What might at first seem to be a simple boulevard vignette reveals layers of visual complexity. We see flat plane divisions alongside depth of field, the contrast between static architecture and the mobility of the street, and the double play of realistic depiction and social display.

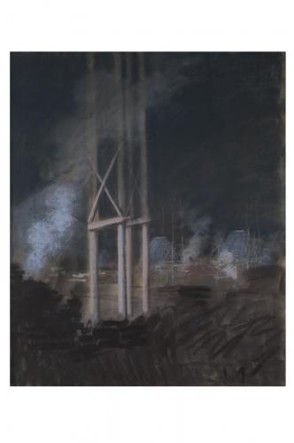

Cantiere (1880–1883).

Cantiere/ Worksite (1883), oil/pastel on canvas, 73×59 cm, Palazzo della Marra, Barletta.

(Credit: Catalogo generale dei Beni Culturali).

There is a striking modernity in this picture, which presents industry within an empty and abstract setting. Rather than depicting a site of collective labour and production, it is pared down to a glyph. We can now connect the work to numerous images that were to follow it, which see industrial landscapes as both barren and atmospheric. I collocate it with František Kupka’s Les Cheminées / Chimneys (1906) of the Musée d’Orsay, a work which is in sympathy with a number of De Nittis’s compositional and aesthetic concerns.

(Credit: https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/les-cheminees-69339).

Cantiere draws close to the cinematic visions of Antonioni in Il deserto rosso or Francesco Rosi’s documentary-style approach to labour and industry in Il caso Mattei. It also seems to prefigure notable photographic works of the twentieth century, such as Charles Sheeler’s Criss-Crossed Conveyors of the River Rouge Plant (1927).

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/265132

In De Nittis’s study, the softness of the pastel destabilises the hard industrial structures, as does the evening register, which renders the austerity of the image mysterious rather than merely severe. Devoid of any element of the picturesque, this is a work of stillness, mystery and modernity.

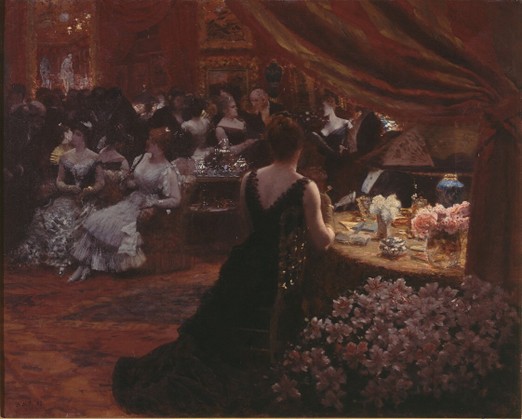

Il salotto della principessa Mathilde / The Salon of Princess Mathilde (1883).

Il salotto della Principessa Mathilde/ The Parlor of Princess Mathilde (1883), oil on canvas, 74 × 92.5 cm, Palazzo della Marra, Barletta.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

This work depicts a social gathering in the salon of Princess Mathilde Bonaparte, the first cousin of Napoléon III. Here De Nittis turns to the mastery of interior light and colour, within a densely populated space. Interestingly, the patron of the work, the princess herself, is embedded at the centre of the crowd rather than being foregrounded. One of the nearer figures is a woman with her back to the viewer, a device which anchors the perspective and guides the eye into the room. These two traits alone give the picture a distinctly modern quality, suggesting the event as observed rather than contrived.

The artificial light is shown rebounding off mirrors and objects, fabrics and furniture. In broad terms this is a social tableau, but one with the emphasis on optical realism, a sense of movement and social dynamism.

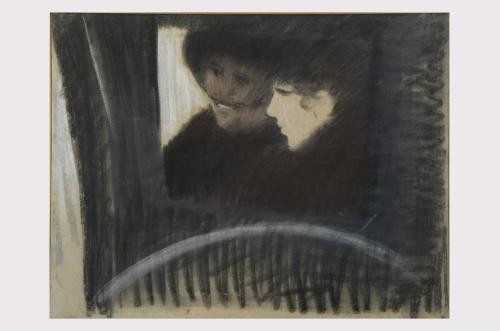

In a Cab / In Fiacre (1883).

In fiacre/ In a Cab (1883), pastel on canvas, 56.5 × 73.0 cm, Palazzo della Marra, Barletta.

(Credit: Catalogo generale dei Beni Culturali).

In this work, De Nittis attends to the most fleeting of gestures. We catch a glimpse of two women through the window of their cab. The half-smile of the more distant figure might suggest a momentary response to something just said; in any case, we are looking into a private space, as if by accident.

Fiacres in Paris were considered spaces somewhere between the private and the public. They could be secret, transitional places where couples met, people gossiped, or deals were made. De Nittis offers an ambiguous, speculative invitation to a narrative. It is ironic that here the painter looks into a cab and that the window frames the scene from the outside inwards; as we know, he often painted from inside a cab, and here the roles are reversed.

The pastel medium adds softness and a dreamlike quality. What we see is not judgmentally invasive or socially satirical. If anything, this is one of those charming, intriguing moments one might encounter in the life of the city.

Coda

Sometimes, happily, I would remain under sudden downpours. Because, believe me, I know the atmosphere well; and I have painted it many times. I know all the colours, all the secrets of air and sky, in their intimate nature. Oh, the sky! I have painted so many pictures of it. Skies, skies alone, and beautiful clouds.

Nature, I am so close to her. I love her; how much joy she has given me. She has taught me everything: love and generosity. She has revealed the truth, the one hidden in myth… Antaeus, who regained his strength every time he touched the Earth, great Earth!

And with their sky, I picture the countries where I have lived: Naples, Paris, London.

I have loved them all. I love life, I love nature.

I love everything I have painted.

Giuseppe De Nittis, Taccuino, parte prima: ‘A Napoli.’

If you wish to support Inner Surfaces, here is the link for contributions:

https://donorbox.org/inner-surfaces-resonances-in-art-and-literature-837503

Acknowledgements and Sources.

Renato Miracco’s An Italian Impressionist in Paris (2022) offers an excellent introduction (in English), and Maria Luisa Pacelli’s De Nittis e la rivoluzione dello sguardo (2019) is a fascinating exhibition catalogue. Christine Farese Sperken’s introduction to De Nittis (2007) is also a very good starting point; it is a succinct account from a leading authority and offers far more than one might expect from such a slender text.

I am also indebted to the essays within these texts by the following authors: Stefano Bosi, Omar Cuccinello, Marina Ferretti Bocquillon, Barbara Guidi, Vasilij Gusella, Robert Jensen, Hélène Pinet, Adolfo Tura, and Isabella Valente (her catalogue entry for Sur la route de Castellamare (1875) in Chiodini (2025)).

Readers are encouraged to consult these publications, and those cited below, for greater depth; any errors in this essay are mine alone.

Bibliography.

Angiuli, E. and Spurell, K., De Nittis e Tissot: pittori della vita moderna (Milano, 2006).

Chazal, G., Morel, D. et al., Giuseppe De Nittis – La modernité élégante (Paris, 2010).

Chiodini, E. (ed.) L’Italia dei Primi Italiani (Crocetta del Montello (Treviso) 2025).

De Nittis, G., Taccuino (Bari, 1964).

Farese Sperken, C. (ed.) Giuseppe De Nittis: Barletta, Palazzo Della Marra Catalogo Generale (Bari, 2016).

Farese Sperken, C., Giuseppe De Nittis: da Barletta a Parigi (Fasano di Brindisi, 2007).

Martorelli, L., Mazzoca, F. et al. Da De Nittis a Gemito (Genoa, 2017).

Mazzoca, F., Zatti, P. et al., De Nittis: pittore della vita moderna (Milano, 2024).

Miracco, R. (ed.) Giuseppe De Nittis: la donazione di Léontine Gruvelle De Nittis, catalogo generale (Roma, 2022).

Miracco, R. et al., An Italian Impressionist in Paris: Giuseppe De Nittis (Washington, 2022).

Pacelli, M. et al., De Nittis e la rivoluzione dello sguardo (Ferrara, 2019).

Picone Petrusa, M., Dal Vero: Il paesaggismo Napoletano da Gigante a De Nittis (Torino, 2002).