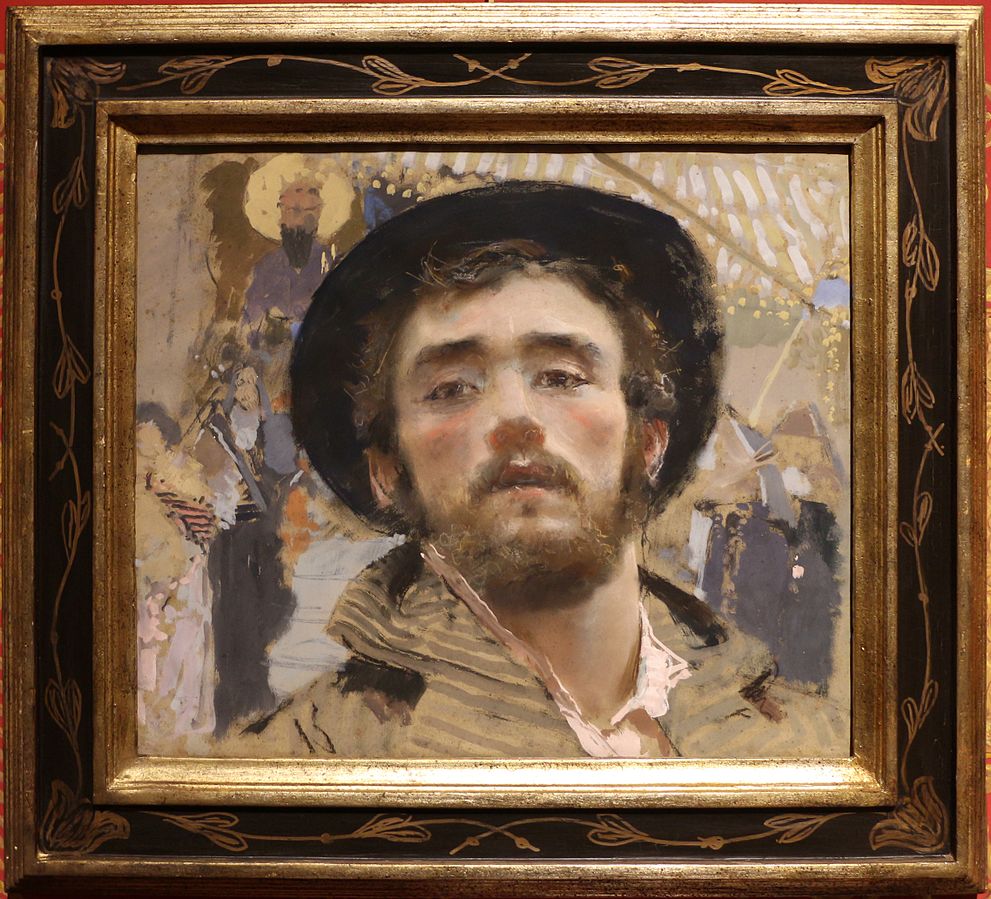

The featured image of this article, Francesco Paolo Michetti’s 1877 self-portrait, (Palazzo Zevallos Stigliano, Naples) offers an introduction to the artist while also immediately conveying the light and colour characteristic of his work. In the words of Marina Miraglia:

The half-open mouth and the intense, passionate gaze express that healthy fullness of life and that trusting, joyful surrender to the natural course of things which are the most authentic themes—beyond the subjects portrayed—of Michetti’s painting. Through these elements, Michetti achieves a profound psychological insight, matched by a formal execution that aligns perfectly with the content, in harmonies of extremely light tones that are remarkably controlled and elegant.

Miraglia also coined, almost in passing, the phrase “the vitality of motion” (or, more literally, “the freshness of movement”) during an interview with Clemente Mariscola at the ICCD (Istituto Centrale per il Catalogo e la Documentazione) in Rome on 17 April 2012. The term arose in relation to Michetti’s use of photography as a tool for studying movement, but it resonates more broadly: as a spontaneous utterance, it suggests the raw fact of an event unfolding in time—its inherent wonder, its Istigkeit, as Huxley might have put it.

To light and movement, one could equally add sound, so exuberant is some of Michetti’s work. Ultimately, in engaging with the work of Francesco Paolo Michetti, we are invited to encounter the ineffable energy and fascination embedded within each apparently ordinary moment.

Michetti chose the agro-pastoral community of his native Abruzzo as his open-air studio and laboratory. This setting offered him starkly contrasting possibilities. On the one hand, it was an escape from the urban and the industrial, providing the inspiration of Nature in its broadest sense — that realm which resists closed systems and rational codification. In this way, it was a locus for the primordial, the mythical, and the unexpected, qualities found in both its landscape and its people. At the same time, this escape was also an encounter with a rural underclass mired in poverty and superstition. Michetti’s pastoral inspiration drew more from the Georgics than from the Eclogues. His vision, though often soaring with beauty and charm, remained rooted in the poverty of his youth.

While Michetti’s art was never intended to be political, his work gained added significance from its timing and context, despite his being neither a fervent nationalist nor a militant social reformer. Throughout his lifespan (1851–1929), the South of Italy was burdened by the persistence of the latifundia system, with huge estates in the hands of absentee landlords and the majority of peasants surviving as day labourers under conditions of chronic poverty. The liberal state after unification failed to resolve this imbalance: the Trasformismo politics of the late 1870s prioritised parliamentary stability rather than structural agrarian reform, leaving rural discontent to fester. Popular agitation, most dramatically the Fasci Siciliani of the early 1890s, revealed the depth of frustration, while reformers such as Gaetano Salvemini began to investigate the realities of peasant life “from below,” exposing the gulf between official rhetoric and lived conditions. Various commissions and debates addressed the so-called questione meridionale, but genuine redistribution of land was continually postponed. Instead, limited initiatives—such as public works, taxation reform, or small-scale tenancy schemes—were implemented unevenly. Against this backdrop of stasis punctuated by the search for remedies, Michetti’s depictions of peasant rituals and rural life take on a double aspect: timeless in appearance, yet bound to a society where the pressure for change was never far from the surface.

Far from any romantic notions of effortless genius, Michetti’s oeuvre was the result of intense labour, and his wide-ranging creativity was disciplined through scrupulous cataloguing and research. While he immersed himself in the humble rural world of his childhood, he returned to it equipped with a rich education — one that brought modern, intellectual, and practical methods to bear on a community still shaped by paganism and superstition. He was also a photographer, conducting experiments that were almost Leonardesque, both in that medium and in painting. He developed his own alternative to tempera: a guazzo (gouache) in which pigments were dissolved in glycerine instead of egg, producing a fluid paint with a luminous finish. He also experimented with techniques for fixing pastel drawings and there is a clear sense that experimentation offered him personal inspiration, as well as forming a vital component of his artistic practice.

There is a restless side to Michetti, one that seems absorbed in the process of creation, often with little regard for the final product. Georges Hérelle, in his Nottolette dannunziane, recalls:

With the pretext that it must be unbearable to own a painting, that is, to have the same artwork constantly before one’s eyes, and that people should be spared such a torment, he got it into his head that, once a painting is completed, it would be best to make a magnificent engraving of it and then destroy the original. In this way, the engraving, kept in a folder, would only be seen by the owner whenever he felt like it. Starting from this idea, he began to search for new and extraordinary engraving techniques, and he wasted a great deal of money in the process.

A more radical testimony comes from Edoardo Scarfoglio, who recalls that Michetti once imagined creating a picture that would destroy itself over time and even fantasised that, once a work had been extensively exhibited, it ought to be torn apart. Scarfoglio glosses:

Thus, his ambition would be to leave behind nothing but a shifting, fluid, and ever-changing legend—like the one that surrounds the names of certain Greek painters, which has come down to us without any documents.

In this, Sabrina Spinazzé perceptively recognises a modern impulse: the privileging of the ‘intellectual elaboration of the image’ over its ‘material execution.’ At the same time, we should not overlook Ojetti’s mocking remark about Michetti’s desire, at the age of 70 or 71, to visit Japan. It seems likely that the artist’s admiration for Japanese culture included its philosophical embrace of transience (mujō) as central to existence. Many traditional Japanese art forms are explicitly structured around impermanence. Michetti’s radical statements may thus be read as both a philosophical affirmation of the transient, ever-changing vitality of the present moment and a practical pursuit of an art form that appears light, unburdened, and perpetually open to renewal.

It is somehow apt that the horizontal compositional style used in Michetti’s large-scale paintings both anticipated the cinematography he experimented with and drew inspiration from classical antiquity. A letter written by Sartorio recalls an evening with Michetti spent pastel drawing from illustrations of herms and Greek vases. In a 1930 letter to Tommaso Sillani, Sartorio wrote:

In the evening, under the lamps, even d’Annunzio would draw; we copied reproductions of the Greek primitives, the herms then unearthed in the Parthenon, and sometimes the Maestro would show us, commenting as he went, countless pastel studies made on Corinthian and Attic vases from the Naples Museum. That was the true Michetti.

As Sabrina Spinazzè has observed, the ‘paratactic organisation’ of some of Michetti’s works appears to draw not only on ancient vases, but also on the structural principles of friezes and sarcophagiforms that, like film, seem to unfold as movement in time and space.

While Abruzzo served as his unbounded en plein air studio, much was also adjusted and worked out in his actual studio, in the convento and even elsewhere. For example, a photograph of a model holding an armful of roots, posing on a terrace in Rome, was part of his studio assemblage for the realisation of Gli serpi (The Serpents). Some of the artist’s rooms in the convento were reported to resemble workshops or laboratories more than traditional studios.

So far, we have set limits on the romantic or mystical interpretations of Michetti’s work, but that is not to suggest such qualities were entirely absent. The ornate and flamboyant prose of Gabriele d’Annunzio, a close friend and artistic companion, often celebrated Michetti’s life and work in elevated terms, accentuating its mysticism, aestheticism, and symbolism. That these descriptions were not only expressed but seemingly welcomed suggests they resonated with some aspects of Michetti’s artistic self-conception. Still, I chose not to foreground such affinities at the outset, precisely because doing so might too easily obscure the important distinctions which also existed.

Now that we have considered some of the grounded, experimental, and systematic aspects of Michetti’s practice, it is worth turning to some of the more compellingly fantastic elements of his work. La raccolta delle zucche (The Pumpkin Harvest), painted in 1872–1873 when Michetti was just 21 years old, is a stunningly beautiful canvas marked by an irresistible strangeness and singularity. Adding to its richness, we also have what amounts to an ekphrasis of the painting in d’Annunzio’s Ricordi Francavillesi (1883), where the work is reimagined in prose.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

In La raccolta, the artist displays, to borrow another expression from Marina Miraglia, a capacity for a heightened realism based on mimesis (un realismo spinto sul mimesis), such as we might expect from a pupil of Filippo Palizzi.

At the same time, this is an oneiric and enchanted scene, bordering on Symbolist work. Fabio Benzi has noted that this element cannot be disregarded, highlighting Michetti’s friendship with Edoardo Dalbono who, in his painting La leggenda delle sirene (The Legend of the Sirens), had recently blended observational fidelity with a dreamlike quality. Dalbono’s painting was at the crossroads between the Romantic concept of the sublime and Symbolist suggestion.

(Credit: Meisterdrucke).

Certain features of Michetti’s style are rhetorical rather than representational, employing composition and figuration to move us beyond realism. This visual rhetoric, I would argue, opens the way to d’Annunzio’s writing, where it finds an even more heightened expression.

In La raccolta d’Annunzio sees the location as Bolognano, in the province of Pescara. However, in this Bolognano scene the background, ‘brings to mind a vast ruin of a pagoda, fragments of Buddhist colossi.’ He continues:

A milky vapour floats in the morning air, rising from the greenish marshes; and the plants with large rough leaves snake along, intertwine on the ground, and rise in clusters upwards. Through this vaporous freshness, men and women come carrying enormous gourds on their heads – yellow, green, mottled gourds, of strange shapes, of strange twists, resembling monstrous skulls, like vessels ruined by swelling, barbaric trumpets, or trunks of large desiccated reptiles.

The clinching moment, however, is when d’Annunzio forces a dramatic paradox: ‘The effect is fantastical, almost dreamlike; yet the scene is real.’ We are in the territory of d’Annunzio’s Symbolism here, a type of aesthetic epistemology which seems to declare that through a heightened and accentuated vision we can reach reality. While this is part of a new artistic vision, it also, arguably, revisits older arguments on imagination (fantastica) and the representational (icastica).

While it is clear that the younger d’Annunzio was inspired by Michetti’s painting and photography, the degree to which there might have been a dialectical relationship between the artists is less easy to establish, and it is not within the scope of this introduction. What is clear is that Michetti was already, in this early work, experimenting with elements of Symbolism and fantasy which can be traced to Dalbono and Morelli. Moreover, the ethereal and vibrant style of Mariano Fortuny – a realm of luminosity, vapour and smoke – played its part.

As we can see from the illustration, a procession of rural workers, together with a rafter of turkeys, walks towards the viewer. A notional depth of field is suggested, as they appear to fan out as they get closer to us, while those most distant blur into what could be an infinite regression. Nonetheless, the colour and focus of the scene fill the front of the picture plane and the overall compositional effect is vivid and shallow, brought forward by a wall.

The procession seems to emerge from what looks like a breach in the enormous wall, described by d’Annunzio above as resembling the “vast ruin of a pagoda.” Vast is the operative term here, as people appear to be encamped on what looks like a higher plain of ground at the top of the structure. The wall therefore also resembles a cliff, especially considering the cataracts that seem to flow down from it, filling the pool on the left of the painting.

In addition to the movement of the processional figures and those high up in the background, we also see a man on the left who looks as though he might be about to step forward. His dog is facing the opposite direction and is barking at some birds — a large flock of which is gliding down from the high wall behind. There are plenty of dynamic poses among the workers: arms akimbo, arms raised or folded to carry the burden of the harvest. The approaching child at the centre of the picture rocks with the rhythm of his gait, and the donkey beside him is lifting its left leg as it advances. The faint image of a shepherd in the background, to the right of the picture, is in a pose that expresses torsion; he grips a staff slung diagonally across his back.

As d’Annunzio observes, there is something aqueous and vaporous about the scene. This holds true for the composition as a whole. While there is a pool on the left, the rich greenery to the right also appears saturated, marshy. The colour of the stonework at the back seems to run and dissolve into a rising mist. Smoke rises from a fire at the top of the wall, mingling with smears of cloud above. The colour palette is beautiful: white, black, brown, red, orange, gold, green, and a sort of electric blue or cerulean. The finest detail is reserved for the costumes and their fabric in the foreground. We should digress for a moment to underscore Michetti’s keen knowledge of Abruzzo fabric, costumes and folk jewellery, which often had an apotropaic role. Most distinctive perhaps are the sciacquajje di Orsogna, the semilunar earrings which add such a distinctive touch to many of his portraits of women.

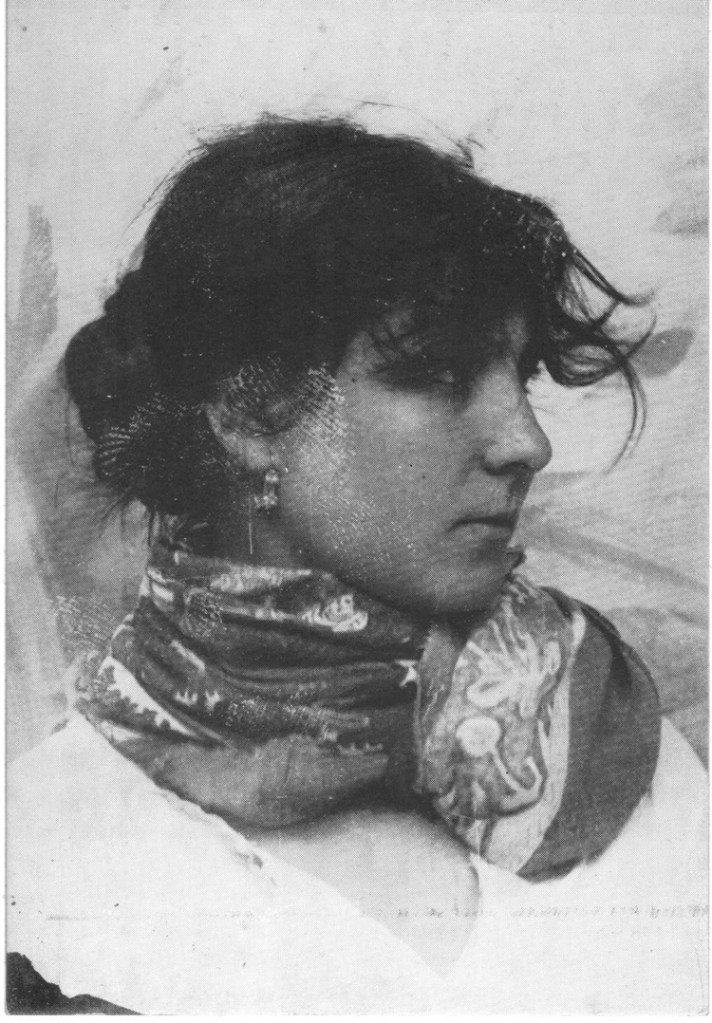

A charcoal and black chalk profile of Annunziata Cirmignani (Michetti’s future wife). (Credit: Stephen Ongpin Fine Art).

To return to La raccolta, the apparent error made by d’Annunzio, who says that the pumpkins resemble “monstrous skulls,” probably stems from misremembering. In the middle of the painting there is a floating anamorphic skull which, incidentally and possibly coincidentally, resembles the human skull in Holbein’s The Ambassadors. Whether Michetti’s skull — probably that of an ox — is intended as a memento mori is not certain. For this viewer, it seems to allude to the primordial, to the deep history of nature, reinforcing, perhaps, the sense that the procession resembles a line of ancestry regressing into the earliest times.

Where the scene in La raccolta is brought forwards by a wall, the Duomo of Chieti fulfils a similar function in La processione del Corpus Domini a Chieti. This work was exhibited in the National Exhibition in Naples in 1877 and it generated a lot of attention, dividing the critics. The painting depicts a procession leaving the cathedral and shows how Michetti responded to the influence of Mariano Fortuny. The great appeal of this work lies in its colour, expansiveness and exuberance. Corpus Domini is a luminous work which bursts with colour and a chorus of processional figures who are leaving the church.

It is not veristic but rather a phantasmagoria of colours, textures and movement. There is a kind of synaesthesia in the painting which complements the sensorial prose of d’Annunzio. The gold of the children’s jewellery, of an icon’s halo and of the band’s brass instruments conveys sound, as does the smoke and sparks of the fireworks that are being set off. A flock of birds in the sky to the left of the composition may have just erupted into flight at the noise of it all. Light brown, light blue, gold and ultramarine punctuate the scene while the costumes, the processional canopy and a decorative ceremonial carpet once more offer close studies of intricate fabrics.

(Credit: WikiArt).

D’Annunzio described Corpus Domini as a ‘sacred bacchanal’ and the nude children, the fireworks, the beautiful women and the exultant light of the painting give it a distinctly pagan vitality. The critics who could not accept the work were perplexed by what they saw deciding that, whatever it was, it could not be considered serious art. Giovanni Costa (1826–1903) saw it as an internally inconsistent and was clearly disturbed that it didn’t offer a true representation of a religious procession. He saw that some areas were carefully drawn while others appeared to have been forgotten. Some colours were in harmony, while others clashed; some figures were rounded, while others were flat. The very brightness and colour of Corpus Domini seemed to provoke in him a feeling of moral disapprobation.

However, while Costa’s response left some room to acknowledge Michetti’s skill, the condemnation of Adriano Cecioni (1836–1886) was unequivocal. He thought that the work was ‘false, mendacious and charlatan’ and that it was little more than ‘a fan in a frame.’ It was Francesco Netti (1832–1894) who ‘got it’, realising that Michetti’s chromatic and sonorous explosion was intentional and offered the public a breakthrough into a new artistic vision influenced by Fortuny and Japanese art. Corpus Domini was to be enjoyed and celebrated for what it was, principally a celebration of the ‘beautiful things’ in life containing as it did ‘women, children and flowers.’

Impressione sull’Adriatico (Impression of the Adriatic), painted in 1880, is a striking example of Michetti’s mastery in depicting maritime scenes. The work was praised by Boito as ‘an Adriatic of lapis lazuli, with bursts of blinding light,’ and it presents a bathing scene set in strong light, just before sunset. As in many of Michetti’s works, the image seems to hover between a mythical study and a portrayal of an unspoilt contemporary rural moment, showing locals bathing by the rocks of Ortona. The brilliance of the canvas—its rich contrasting colours, the subtle tones of the sunset and the surface of the water, together with the serenity and innocence of the bathers—makes it a luminous and radiant work. The interplay of nudity, partial nudity, and gestures of modesty situates the scene in an interstice between ethnographic idealism and aestheticised reverie, between purity and pagan sensuality. Its dreamlike atmosphere recalls Morelli and Dalbono, while the treatment of colour and light reveals the influence of Fortuny. This warm painting reflects Michetti’s deep sympathy with the communal rhythms of life in Abruzzo during his time.

(Credit: Meisterdrucke).

Il voto (The Vow), painted in 1883 and also exhibited in the Esposizione di Roma of that year, is an exceptionally large canvas (250 x 700 cm) housed in the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome. Begun in 1881, it depicts a scene from the feast of San Pantaleone (Saint Pantaleon) in Miglianico: panteleimon in Greek means “all-compassionate,” and the saint was the patron of midwives and physicians, also invoked for protection against illness and headaches. His feast falls on 27 July, and we may therefore assume that the oppressive throng of pilgrims is assembled in the heat of a summer’s day. The painting presents the dark interior of a crowded church where figures press together: some stand, some sit, while others advance by prostration towards the effigy of the saint. It is an anthropological and expressive work, raw in its intensity, and reminiscent of the popular scenes painted by Courbet and Jules Breton, as well as managing to capture archaic ritual in the manner of Giovanni Verga.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

One memorable detail of this work was that it was provocatively labelled ‘non-finito.’ More accurately, it was of course a ‘finito, non-finito’, that is to say Michetti intended the work to expound the lessons of Fortuny, combining close study with more impressionistic brushwork. It also blended well with the anti-modern, anti-rationalist focus of Angelo Sommaruga’s Cronica Bizantina and the sensual decadence of the writing of Gabriele D’Anunzio.

I morticelli is a study of the funeral of two children, painted in 1880; this work is held in the Museo Nazionale d’ Abruzzo. The horizontal format emphasizes movement, while the close attention to facial expressions captures the individual responses to the tragedy in the moment depicted. The bleakness of the scene is softened by its natural setting, with flowers and sunlight. There is also a choral dimension: the participants represent members of the local community, including the priest, the musicians, and the children and adults of the village. The funeral unfolds in a liminal space, as beyond the idyllic rural setting stretches the unbounded horizon of the Adriatic Sea. This is a moving study of nineteenth century misère which is alleviated by nature and the sympathetic gathering of a community. I morticelli also shows awareness of Courbet’s Un enterrement à Ornans (A Burial at Ornans) and suggests that Michetti was aware of the French artist’s realism and respect for rural life.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

La figlia di Jorio (Jorio’s Daughter), the 1895 version, won first prize at the Venice Biennale that same year. This huge canvas (280 × 530 cm) has a horizontal format and reads like a cinematic frieze: a fleeing woman strides from right to left before a chorus of men whose faces display a range of reactive expressions. La figlia evokes a spectrum of emotions in the crowd that is watching her pass—curiosity, lust, admonition, mockery, and contempt seem particularly central. Here, too, Michetti demonstrates a keen study of movement: the fleeing woman’s feet propel her forward, with the left heel about to touch the ground while she rises onto the ball of her right foot. Her face is not visible, as she is in the act of covering it with her bold red mantle. She moves with energy and confidence, conveying a stately, sober, and austere presence.

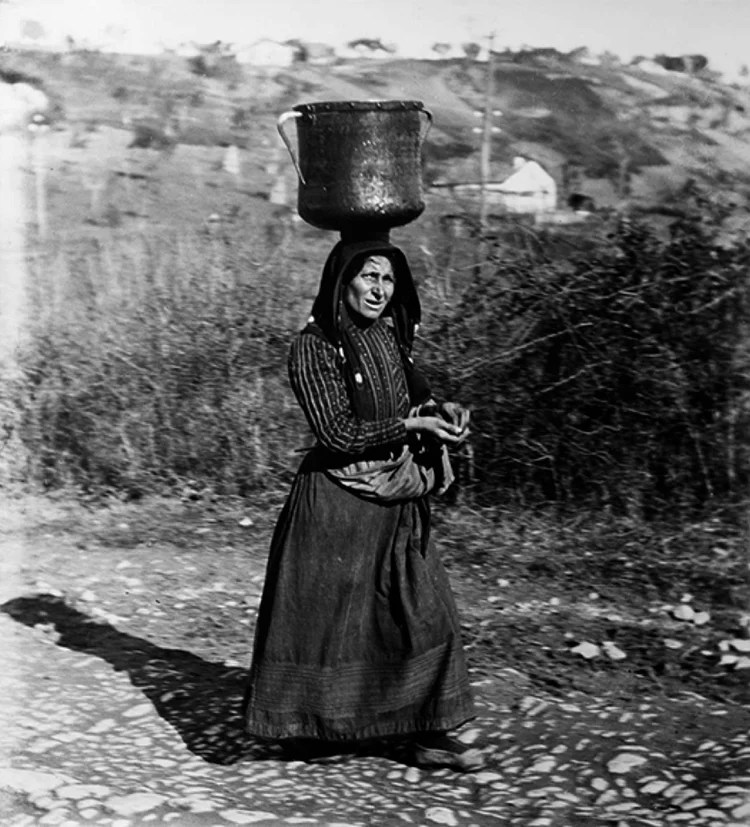

The Maiella mountains form a dramatic backdrop; the ridge line is sharply defined and bathed in high, bright light. There is a radical photographic crop of a standing male figure at the right of the composition, and another realistic detail is the woman carrying a load on her head, who is still but turning back momentarily, with a shawl wrapped around her. This work illustrates well Michetti’s refinement of disegno, a process aided by his photography. The same skill is also documented by d’Annunzio, who refers to Michetti having a ‘high operation of the intellect’ which was able to choose the right line, out from ‘a mystery of countless outlines.’ This new leanness and precision might also have been encouraged by Michetti’s interest in Japanese culture, as here the aesthetic concept 間 (ma) encourages respect for the space, or rather the living interval between things.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

A succinct and fitting narrative for Jorio was furnished by Ettore Janni. He relates the daughter’s story as follows:

She gives herself to the man who opened her arms to her in a gesture of tenderness… and the daughter of Jorio becomes the talk of all. The rigid and cruel virtue of the village turns savagely against her with shame and mockery… and a storm seizes and shatters the soul of the daughter of Jorio… she rises again, looks around her… now she will carry out her revenge.

The daughter of Jorio becomes the scourge. She is the demonic seductress, the sorceress who enchants men and drives them mad… and around her swirls an aura of terror, of desire, of sacrilege. Then the scourge falls and she atones more for her revenge than for her first sin.

She lives on in her solitude… Is she dead? Who knows?… but her spirit still wanders the land, passing through the veils of a legend that is one of sin, but more of suffering and sorrow.

The rigid mores of rural life, patriarchal double standards and a kind of misogynistic myth-making close in on the daughter, who is only named as the property of her father. Nonetheless, Michetti succeeds in turning the myth and solitude of the daughter into something powerful and worthy of respect. Her upright posture, modesty and purposeful stride contrasts with the wave of recumbent men whose faces are distorted by ignorance.

Gli storpi is a work of 1900, painted on a large canvas (380 × 970 cm), and is housed in the Museo Michetti in Francavilla al Mare. It can be paired with Gli serpi of the same year, which is also held in Francavilla. Both works were executed in a short period, following a long process of preparation and planning, in order to be ready for the 1900 Universal Exposition in Paris.

Gli storpi illustrates an account by the anthropologist Antonio de Nino, who described the procession of the sick and infirm of Casalbordino. This pilgrimage took place on the first Sunday of August, to commemorate the appearance of the Madonna dei Miracoli, which had occurred in 1527. When we compare Michetti’s painting with his photographic and documentary sources, we are left with the impression that he aimed for a relatively contained realisation of the scene. As well as colour, expression and movement, there is a cool positivist detachment that tempers his work. The extant photographs taken by Michetti which informed the painting had a biting realism which showed physical deformation and the atrophy of limbs, the stooped and the hunched, and beggars with ulcerous skin lesions.

Gli storpi captures all the surprise of a single moment: for example, on a hill at the centre of the canvas, two oxen dominate the composition with all the force of chance. They seem to suggest a robust and vital aspect of nature, rising above the smaller, more shadowy vale of human suffering beneath them. The upper slope of the hill and the oxen are bathed in golden sunlight, which forms a luminous band across the centre of the composition.

(Credit: Rubricando).

We know that Gli Serpi was the result of a field trip made in 1884 with Antonio De Nino, together with Costantino Barbella and Gabriele D’Annunzio, to San Domenico di Cocullo for the Feast of the Snakes. Michetti returned from the visit with extensive photographic documentation. This religious celebration took place every year on the first Sunday of May. According to local folklore, the harmless snakes used in the ceremony, when wrapped around the breasts of mothers who were not lactating, could restore their milk. San Domenico of Cocullo was considered a thaumaturgical saint, believed also to protect against snake bites. Unsurprisingly, the feast has pre-Christian roots, possibly tracing back to the worship of Angitia, the ancient Roman goddess of snakes.

(Credit: Rubricando).

There is a magical quality to Gli serpi with its vivid colours of gold, green, splashes of red and bright touches of white. The mixture of closely defined elements and impressionistic suggestions, also notably found in Il voto, makes this another dreamlike study. The clouds of incense and a flowing, almost dissolving, canopy of gold in the right half of the composition also contribute to this atmosphere.

Turning to Michetti’s workplace contexts, in the summer of 1880 his project for a studio on the beach at Francavilla al Mare was completed; in the same year, he established a creative collective called the Cenacolo delle Arti. In 1885 he purchased a disused fifteenth-century Franciscan convent in Francavilla al Mare, Santa Maria del Gesù, which he converted into his studio and a meeting place for the cenacolo, later known simply as il Convento. Within its walls, a circle of artists and intellectuals gathered, including Gabriele D’Annunzio, Costantino Barbella, Paolo De Cecco, Francesco Paolo Tosti, Edoardo Scarfoglio, and Antonio De Nino. Il Convento thus functioned as a site where painting, literature, music, material culture, and ethnographical scholarship intersected, grounded both in local traditions and in broader cultural developments.

There is a passage by Italo De Sanctis that describes the context of the cenacolo with warmth, as a kind of utopia:

[Michetti] had grown fond of that quiet countryside, all fresh with vegetable gardens and orchards. One could get by with little money, in a solitude that felt somewhat wild. The people were kind, and the wine was like the people. The women—beautiful, upright, and graceful—wore white blouses and short skirts, showing their full breasts and shapely arms without the slightest malice. The men were solemn, like monuments.

He invited friends and colleagues, who came eagerly and formed the cenacolo—the circle that gave Italy its loftiest poetry, its most forceful painting, its most heartfelt song. Francavilla was the ideal place for their capricious way of life; and there they lived in the full grace of the Lord, in the joy of creation, the fever of work, the intoxication of song, the raptures of love. Days of good humour, of complete joy!

Rosy dawns followed one another in the forgetting of the seasons, and a musical enchantment filled the ecstasy of light, a fragrance of spikenard hung in the air. Young, free, and carefree, they never felt fatigue. Days of intense and fruitful work were followed by nights of delirious joy, under the moonlight. Even the most enchanting Amazons would come down from Chieti to the shore, to make their lives more like a fairy tale, in that little corner of paradise.

Both the sources and concerns of Michetti’s art were multiple. The cenacolo provided interdisciplinary input into his creative process, while his own work undoubtedly inspired his companions, most notably d’Annunzio. Equally important, perhaps, was the conviviality and mutual encouragement that such a circle must have fostered. It is possible to work back from Michetti’s paintings, tracing the influence of those around him: musical, documentary, ethnographic, dramatic and symbolist elements can all be found in his art. Yet the greatest reward comes from contemplating the final unified whole and, with it, the particularity of Michetti’s project.

Photography was an extremely important medium for Michetti. He used it to deepen and develop his drawing and painting, but also recognised it as an artistic medium in itself. In this context Miraglia observes how ‘the strength of photography lies precisely in its language, whose prerogative is exactly to remain constantly balanced between denotation and connotation, between documentation of reality and figurative reshaping.’ Photography could capture a moment and freeze it with a level of detail previously unachievable but it would also remain a representation, an act shaped by the decision of a photographer which also imposed sharp limits through its cropping of an image.

Michetti used photography in varied ways and for different projects. At first, he employed it for portraits and for studies of posed models that would inform his compositions. He also photographed the rural life of the Abruzzo, including its choral gatherings. Through experiments with photography and cinematography he was able to capture a realistic sense of movement, developing his own film camera and, later in 1922, he even invented a cinema projector. His legacy further includes experiments with stereoscopic photography: this, together with his use of life models and terracotta models, helped him attain a sense of volume and plasticity in his painting.

Examples of Michetti’s photography. (Credit: Studio Trisorio.)

This was a period of rapid technical innovation which saw improvements in the compactness and portability of cameras; something tied, in turn, to pre-coated plates of film that used the gelatine silver bromide process. Such developments in film also significantly reduced the time required for a figure to hold a pose. It is not hard to imagine how photography enhanced Michetti’s pictorial representation, particularly in his treatment of light, line, and movement. Its influence is evident in his portraits in charcoal and chalk, executed on paper prepared with dried clay, where he applied colours in broad patches corresponding to areas of light and shadow. Photographs helped him to capture expression and detail, as well as informing him about light and shade. Michetti’s charcoal portraits seem to suggest a clear debt to photography.

Michetti developed a dialectical relationship with his medium, which allowed him to engage more deeply with his subjects. He moved fluidly between drawing, painting, and his photographic sources. It seems highly likely that photography played a crucial role in enabling Michetti to realise a pared-down style of disegno. For example, Jorio demonstrates a notable austerity of line, and Michetti’s general catalogue contains a number of monochrome studies—both of figures and of landscapes—that may have been inspired by his experience as a photographer. At the same time, we should also cite the likely influence Japanese ink painting as an influence on his monochrome works.

Michetti – monochrome studies. Credit: Mutual Art and WikiArt.

The binomial nature of black and white photography (as well as other very significant contextual factors) may also have influenced the proliferation of rapid pencil sketches made by him post-1910.

Pencil sketch, post 1910 ca. Credit: Gliubich, casa d’aste.

Another area of restraint, in which the effusive manner of Fortuny cedes to a fifteenth century sobriety, is in Michetti’s Illustrations for The Amsterdam Bible from the period 1893-1897 (for illustrations, see Strinati 1999 (b) p. 151.)

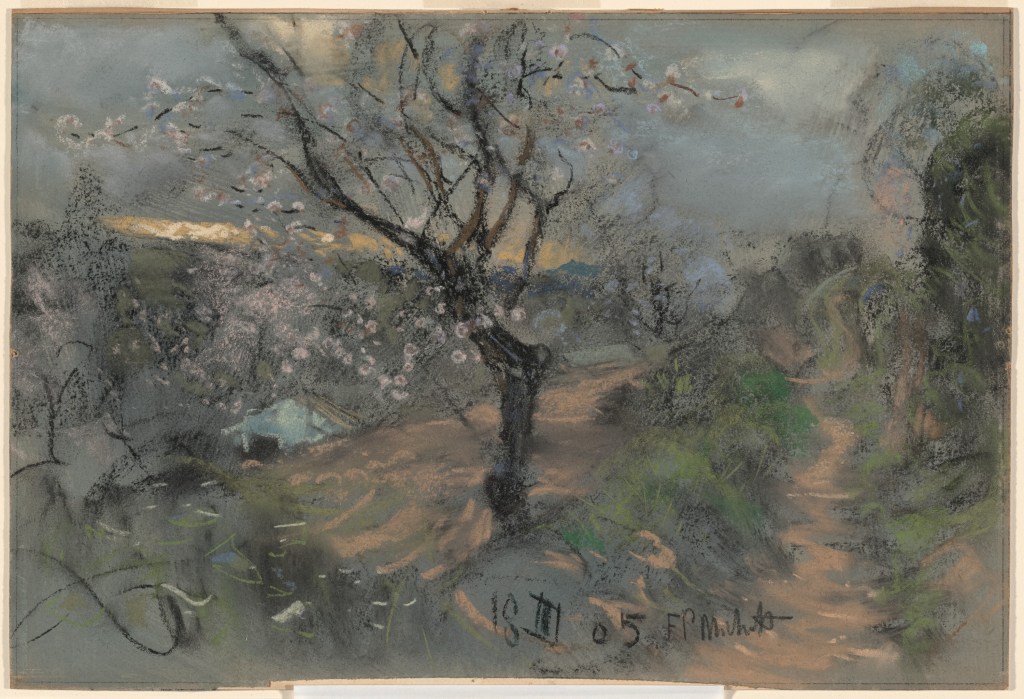

The breadth of Michetti’s work would make any introduction fall short in some way, however there are more aspects of it which deserve to at least be mentioned. Michetti was a landscape artist and he excelled in the creation of landscapes which were often, although not exclusively, executed in pastel and tempera (or other mixed media). Such was Michetti’s mastery of pastels it is often stated that they were the inspiration behind Giuseppe Casciaro’s adoption of them. Casciaro is said to have been struck by the pastels exhibited by Michetti in the Promotrice in Naples of 1885. Michetti’s studies bridge the Neapolitan and French en plein air artistic tradition, offering stunning works that convey brightness and immediacy.

A hillside path with blooming cherry trees. Michetti, 1905 (Credit: National Gallery Washington).

While on the subject of the study on nature, it is worth tracking back again to his work as a photographer. From the 1890s onwards the Michetti archives have pictures of trees, leaves, flowers, rock formations, seaside rocks and rocky rivers. Some of the close-up photographs reveal an interest in natural textures that anticipate the work of the American photographer Edmund Weston whose ‘straight photography’, developed from the 1920s onwards, included close-up images of shells, cabbages, peppers, rocks and dunes.

Michetti’s skill at rendering idyllic charm and grace has perhaps received little attention here and we should at least make passing reference to it. La pastorella (The Shepherdess) in the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome can stand to represent his poetic grace in the depiction of rural scenes. This work of 1887 offers an example of the many exuberant, intensely colourful and technically skilful pastoral scenes that Michetti completed.

(Credit: AcquistoArte).

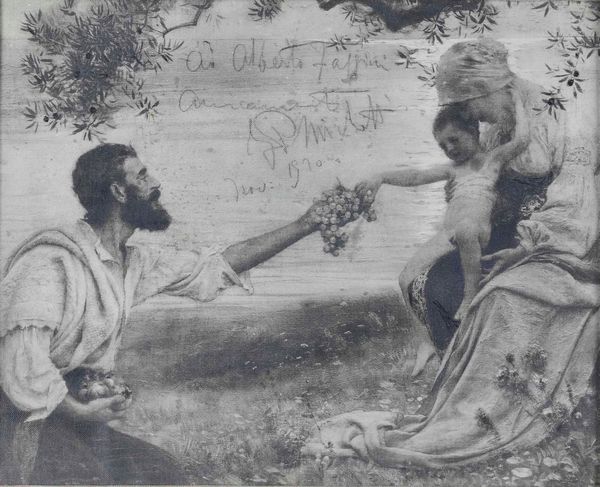

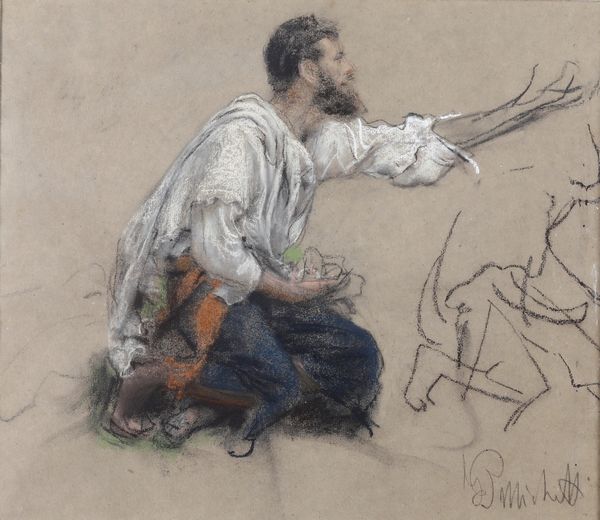

At the later date of 1896 we have a return to such grace in L’offerta (The Offering) in which Miraglia sees ‘Pre-Raphaelite reminiscences.’ This work, which is in the Royal Collection in the Villa Savoia, was completed for Queen Elena; in it the queen is represented as a kind of secular Madonna. She is depicted sitting down, with her son Giorgio in her arms, receiving an offering from a kneeling shepherd. Clearly, this apparent return to an earlier style of painting was considered fitting for the commission.

(L’Offerta (studies). Credit: ANCA, Case d’Asta).

Michetti was a great portrait artist. His skill in this genre is represented in his self-portraits, his studies for large-scale paintings, in formal commissions and in work for friends. We began with one of his self-portraits, so here we can look at a study of a friend and fellow artist of the cenacolo. The Portrait of Costantino Barbella (ca. 1888) depicts the sculptor from Chieti with two of his most famous sculptural works on either side of him. On the left is the figural group Canto d’Amore (Song of Love) while on the right we have Canesto d’Amore (Basket of Love). This warm portrait captures what d’Annunzio referred to as the handsome Barbella’s ‘nostalgic eyes of a shepherd and [his] thick pirate’s moustache.’

(Credit: Archivio di Stato di Chieti).

Michetti’s productivity did not end there: he produced etchings; designed decorative fabric motifs; carried out anthropological research on textiles; studied flowers and vegetation; created designs for stamps, postcards, and book illustrations (including the Amsterdam Bible, as mentioned earlier); and designed a classically decorated label and amphora for the Abruzzo liqueur Corfinio. He also worked on fabrics and theatre sets, together with actors’ costumes; drew up architectural plans for his Casino al mare and designed furniture; and even created unique curtains and decorative frames for his paintings.

With this in mind, it is little wonder that Ojetti recorded the artist saying, “I believe, you know, that no one has ever worked as much as I have in their life.” What is more perplexing perhaps is how his fame has slipped from international recognition and how little is in print about him in English. I hope that this short and incomplete summary of his achievements might stimulate some wider interest in this great artist from the Abruzzo, who was educated in Naples.

[This article relies on the Italian scholarship listed in the bibliography below. My intention is to introduce Michetti to an English-speaking audience and to encourage readers to consult these secondary sources. Any errors or infelicities are my own .]

Producing these articles requires care, time, research, and resources. Contributions to help sustain this exploration would be greatly appreciated.

https://donorbox.org/inner-surfaces-resonances-in-art-and-literature-837503

Bibliography

(The two volume general catalogue for Michetti, listed below, features articles by Fabio Benzi, Gianluca Berardi, Teresa Sacchi Lodispoto and Sabrina Spinazzè. These are names worth searching for on the internet and the Galleria Berardi of Rome has a website and a Facebook page which is well worth consulting.)

Benzi, F. (et al.) Francesco Paolo Michetti: catalogo generale volume 1. Milan, 2018.

Benzi, F. (et al.) Francesco Paolo Michetti: catalogo generale volume 2. Milan, 2024.

Caputo, R., La pittura Napoletana dell’Ottocento (2 vols.) Napoli, 2017.

Del Cimmuto, P., Il vero e il sentimento. Ascoli Piceno, 2016.

Di Tizio, F., D’Annunzio e Michetti: la verità sui loro rapporti. Casoli (Chieti) 2002.

Garofolo, D., Francesco Paolo Michetti: il genio fotografo. Silvi Marina (TE) 2015.

Janni, E., F. P. Michetti in ‘La Lettura’, VX, 1914, 62, pp. 967-969.

Miraglia, M., Francesco Paolo Michetti Fotografo. Torino, 1975.

Strinati, C. (Ed. (a)) Francesco Paolo Michetti: dipinti, pastelli, disegni. Napoli, 1999.

Strinati, C. (Ed. (b)) Francesco Paolo Michetti: Il cenacolo delle arti, tra fotografia e decorazione. Napoli, 1999.

Appendix: Some of the lesser known figures cited in this article.

The following are brief biographical notes on artists, writers, and cultural figures who were part of Francesco Paolo Michetti’s circle or who influenced and collaborated with him. They are included to provide context for the references made in the text and to highlight the broader cultural network surrounding Michetti. I have not included details of the more widely known artists and literary figures.

Costantino Barbella (1853–1925) – Abruzzese sculptor, known for terracotta depictions of rural life. A close friend and collaborator of Michetti, they shared an interest in elevating peasant culture through art.

Camillo Boito (1836–1914) – Italian architect, art critic, and novelist. A leading theoretician of architectural restoration in Italy, he also wrote extensively on art and aesthetics. Boito’s critical writings engaged with contemporary painters, including Michetti, influencing public and scholarly reception of their work.

Adriano Cecioni (1836–1886) – Painter, sculptor, and critic of the Macchiaioli movement. His realist ideals resonated with Michetti’s own pursuit of naturalistic truth in art.

Giovanni Costa (1826–1903) – Italian painter and landscape artist, associated with the Macchiaioli and later the “Etruscan School.” Costa was influential in promoting naturalistic painting and mentoring younger artists, including Michetti, shaping his approach to light, landscape, and realism.

Paolo De Cecco (1864–1928) – Polymath from Chieti, Abruzzo: painter, writer, inventor, and accomplished mandolinist. A cultural figure tied to Michetti’s circle, his paintings of rural Abruzzo paralleled Michetti’s own subjects, while his versatility made him a hub of local artistic life.

Italo De Sanctis (1869–1925) – Painter from Abruzzo whose portraits and genre scenes show Michetti’s influence. A younger colleague, he carried forward Michetti’s artistic legacy in the region.

Antonio De Nino (1837–1907) – Archaeologist and folklorist from Abruzzo. His studies of regional traditions complemented Michetti’s use of Abruzzese rituals, folklore, and peasant life as artistic subjects.

Georges Hérelle (1848–1935) – French philosopher, translator, and ethnographer. He introduced Italian Decadent literature to French audiences, translating works by D’Annunzio, Deledda, and Serao. His scholarly interests also encompassed Basque folklore and regional history, and he maintained close intellectual ties to Michetti and other figures in Italian artistic circles.

Ettore Janni (1865–1937) – Writer, journalist, and critic. Part of the intellectual exchange around Michetti, engaged in literary and artistic debates that intersected with Michetti’s milieu.

Francesco Netti (1832–1894) – Painter from Apulia, known for historical and genre scenes. His detailed realism and interest in local life resonated with Michetti, and he participated in exhibitions that brought him into Michetti’s artistic network.

Ugo Ojetti (1871–1946) – Journalist, critic, and writer. A younger figure in Italian cultural life, he critically engaged with Michetti and helped frame his place in Italian art history through journalism.

Giulio Aristide Sartorio (1860–1932) – Symbolist painter and later Secessionist. His large allegorical works echoed Michetti’s own monumental style; they shared exhibition spaces and artistic ideals in Rome’s cultural life.

Angelo Sommaruga (1857–1941) – Publisher and journalist. Founder of Cronaca Bizantina, he provided a platform for many writers and artists in Michetti’s orbit, including Gabriele d’Annunzio, one of Michetti’s closest collaborators.

Tommaso Sillani (1888–1944) – Journalist, writer, and diplomat. Though of a younger generation, he connected with Michetti’s extended intellectual network, particularly in literary and political discourse.

Edoardo Scarfoglio (1860–1917) – Journalist and writer, co-founder of Il Mattino. His sharp journalism and literary ties linked him to Michetti’s cultural circle, especially through shared Abruzzese roots and connections with other intellectuals like d’Annunzio.

Gaetano Salvemini (1873–1957) – Historian, politician, and anti-fascist activist from Italy. Though not an artist, he moved in intellectual circles connected with Michetti and others from Abruzzo, contributing to the cultural and political discourse of the period.

Francesco Paolo Tosti (1846–1916) – Abruzzese composer, famed for his songs. Shared regional background and friendship with Michetti; both carried Abruzzo’s cultural voice beyond Italy (Tosti in London, Michetti in Paris and Rome).

Links and videos:

Accessed on 30 September, 2025.

Michetti and photography – interview with Marina Miraglia.

https://youtu.be/5l5exWgDfJ0?si=LTEooEyijo6Zcb6g

Fabio Benzi speaking about work on Michetti’s general catalogue, back in 2018.