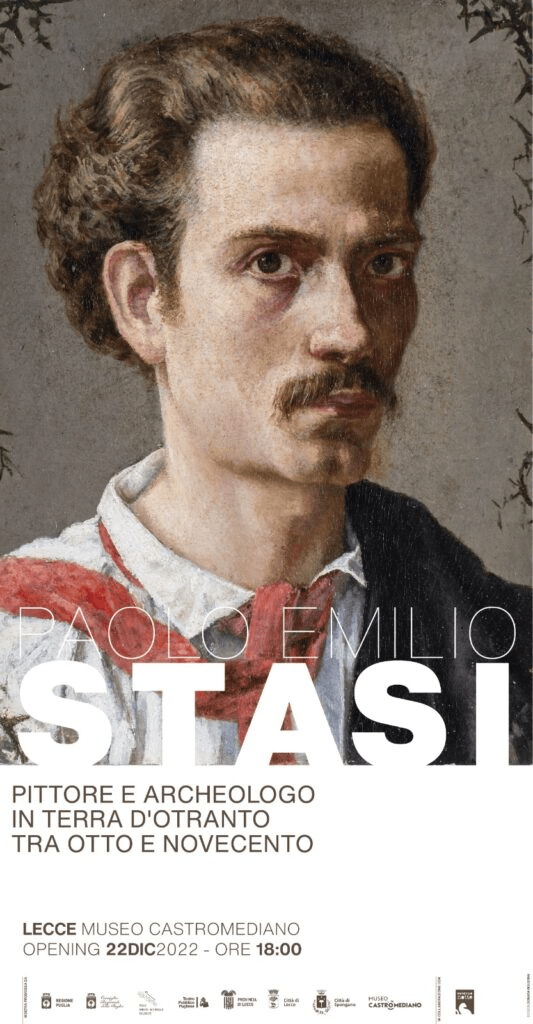

Giuseppe Casciaro’s first lessons were with Paolo Emilio Stasi from Spongano in Puglia. As Stasi’s artistic importance, and hence his influence on Casciaro, seems a little understated in the literature, it is worth emphasising that he was a versatile painter who captured various aspects of the people and landscapes of Salento. Vito Carbonara justly refers to Stasi as ‘eclectic’ and ‘brilliant.’ Images from works exhibited in the Museo Castromediano of Lecce, help us to discern something of the culture passed on to Casciaro.

The following link offers three images of Stasi’s work, the image below included:

https://www.valerioterragno.it/artisti-salentini/183-stasi-paolo-emilio

Stasi’s commitment to his locale also extended to archaeological work, such as the Grotta Romanelli, a palaeolithic site near Castro. This comprised a single room about seven metres above sea level with an adjoining tunnel, which yielded hundreds of artefacts. Castro, more relevantly to our focus here, was a favourite landscape of Casciaro’s, where he carried out a number of studies.

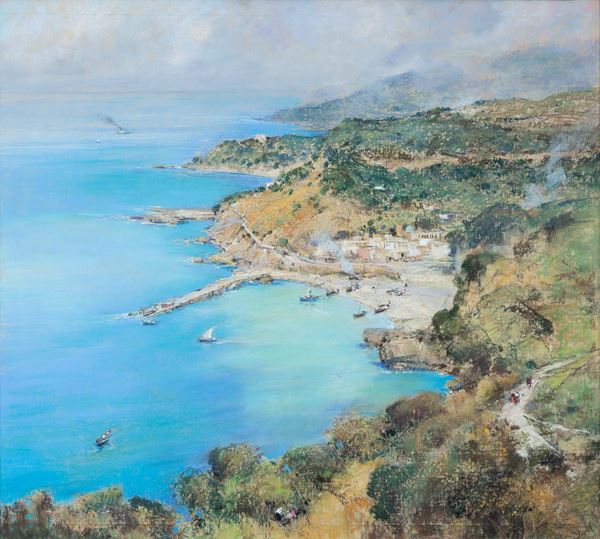

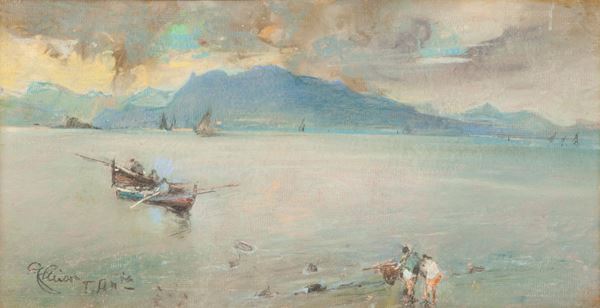

Giuseppe Casciaro, Marina di Castro (1918) Museo del Novecento Napoletano.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

Casciaro grew up in difficult circumstances, as he was orphaned at 12 years old. He was, at least, supported by a rather strict uncle who was a priest; in his youth he was educated in a liceo (il liceo-ginnasio di Maglie) and was destined for further study in Naples. While his uncle expected him to study medicine there, Casciaro enrolled in the Accademia di Belle Arti, convinced that he was to become an artist. When his deception was discovered, by someone from his region who was also resident in Naples, his uncle immediately cut his allowance. It was only through the kindness of his aunts Carolina and Carmela that he received 5 lira a month. This very modest sum was smuggled to him in his monthly laundry bundle – according to the account of Alfredo Schettini.

In all events, in the face of severe poverty, he went to study under Gioacchino Toma and Stanislao Lista at the Accademia in Naples. However subdued his circumstances, Casciaro was, from the outset, a spirited and determined individual. As documented by Vito Carbonara, accounts of his time at the Accademia record how he was reproached for his absences from classes in perspective and, in July of 1881, he was reproached for ‘boorish behaviour (maniere villane)’ used against a classmate.

Returning to Casciaro’s teachers, Toma was committed to verismo and was famous for his studies of historic and genre subjects, as well as landscapes. We can note some similarities in the artists’ depiction of mood through a comparison of Casciaro’s portrayal of his wife Giovina, and Toma’s representation of women.

Gioacchino Toma, Luisa Sanfelice in carcere, 1874, Capodimonte.

(Credit: Wikipedia).

Giuseppe Casciaro, Portrait of Giovina.

(Credit: Artnet).

Equally, if we look at Toma’s work La pioggia it is not too far from Casciaro’s emotional and visual repertoire.

Gioacchino Toma, La pioggia (1882-85 ca.) Gallerie d’Italia, Napoli.

(Credit: Wikipedia).

Giuseppe Casciaro, Pioggia al Vomero.

(Credit: Galleria Pananti Casa d’Aste.)

While Toma’s overall artistic project was very different from that of Casciaro, in some aspects of their landscape work we can see affinities. In some instances, there is a shared spirit of introspection and perhaps sadness. Toma’s approach to art was intimate, essentialist and melancholic. His studies were often situated in sparsely decorated rooms and the tonality of his paintings tended towards the dark and melancholic. Casciaro’s landscapes could similarly evoke a sense of silence, solitude and introspection.

Giuseppe Casciaro, Ischia.

(Credit: Capitolium Art – Casa d’Aste.)

Stanislao Lista is remembered primarily for his sculpture: he was an artist also committed to realism, mediated through his own style, which was arguably a blend of Neoclassicism and Romanticism. A dedication to verismo is evident from Lista’s portrait bust of his father.

Stanislao Lista, Portrait of Giuseppe Lista (1867) Napoli, Accademia di Belle Arti.

(Credit: Fondazione Zeri.)

This work is the fruit of Lista’s commitment to studying sculpture from life, dal vero. The portrait is frank and far from flattering. Beyond this, the edges of this work were deliberately left rough, perhaps to indicate the new direction that Lista was taking and mark a departure from the polished finish expected in an academy: Lista eschewed the vision of a style of sculpture based on an idealised classical model. He saw copying from life, through rapid modelling in clay and through disegno as a means to capture the essence of a live model. For Lista, drawing and modelling from life could capture the true spirit of a subject that otherwise might become lost in the lengthy process of carving marble, particularly in a manner which was overly reliant on classical precedents and a fixed academic pedagogy. Responding to life models with the primacy of drawing, one could create a work which was ‘a natural and necessary consequence of the subject one wants to address.’

The new energy and realism that came from Lista’s teaching was carried forward by some of his former pupils into Paris: Gemito’s ‘Little Fisherman’ and Achille D’Orsi’s ‘Parasites’, for example, managed to divide opinion at the ‘Exposition Universelle de 1878’ in Paris.

Vincenzo Gemito, Il Pescatorello (ca.1876) Museo di Capodimonte.

(Credit: author’s photograph).

Achille d’Orsi, I Parassiti (1877) Museo di Capodimonte.

(Credit: author’s photograph).

Traditionalists saw these works as ugly and ignoble, while Camillo Boito wrote of ‘beauty renewed in the ugliness of the real.’ These Italians were drawing interest in Paris for their studies from life and for choosing an unflinching realism. (See Valente, 2014.) This digression into sculpture is valid for a number of reasons. While Lista was primarily a sculptor, he was also an artist: he was skilled in disegno and he worked as a teacher of painting. Lista had a number of talented pupils under his tutelage, beyond our Casciaro. Along with Domenico Morelli, he taught Vincenzo Migliaro, Vincenzo Irolli and Gaetano Esposito, to name but a few.

With this in mind, Lista would certainly have extolled the value of the direct channelling of a truthful, and fleeting, moment in painting. In Casciaro’s work, like that of Lista, we can see the spirit of innovation anchored in tradition. The notion of not dissipating inspiration with intermediary stages would have appealed to Casciaro, who became a superlative en plein air pastel artist who, according to contemporary accounts, worked with pastels with fearsome speed and instinct. Casciaro was industrious, ‘un accanito operaio della pittura’; he was always outdoors and he worked on Sundays (occasionally being subjected to colourful insults for such sacrilege by the passing faithful on their way to church).

The journalist and arts’ critic Ugo Ojetti (1845-1924) expressed a reservation (which contained a simultaneous element of flattery) that Casciaro’s work could suffer as a result of his facility with a brush: ‘Casciaro aveva un solo nemico: l’abilità della mano.’ In a similar vein, Rosario Caputo has suggested that Casciaro’s dexterity and his creative capacity meant that his work often fell into two broad categories: one was more commercial, more immediately attractive, and repeatable, while the other was more intimate, more refined and more sought after by the discerning (Caputo (2017)). While this is surely so, we should be careful not to go as far as representing Casciaro to be a sort of blindly energetic craftsman, a bundle of astute reflexes that could imitate natural effects.

There are a number of reasons for rejecting this characterisation. The extraordinary breadth of Casciaro’s art collection (he had his own personal museum in his house) and his education at the Accademia do not offer us the background of a mere painter-craftsman. However self-possessed he might have been, it is impossible that he did not explore what he was doing reflectively and vigorously within the artistic traditions of his time and the past. Casciaro held numerous academic roles, belonged to a series of artistic circles and became leader of one himself, Il Gruppo Flegreo (1927-1929), which met in his Villa in the Vomero in Naples. Even if, in the act of painting, he was open to the immediate impressions of nature and subject to the quickness of his technique (he could, at times complete from ten to fifteen landscapes in one day) working beneath this facility would have been a sophisticated intellectual and intuitive understanding.

Casciaro’s debut of 1887 at the ‘Promotrice Salvator Rosa’ brought him the praise and support of two more very important figures associated both with the Accademia and with the development of Italian art in the nineteenth century as a whole – Domenico Morelli and Filippo Palizzi. We know that he found this praise to be heartening and inspirational – we also know that he subsequently attended their studios, constantly exhibiting at the Promotrici until 1911. A less happy consequence of Casciaro’s emergence as a talent stemmed from the jealousy of some of his peers. Vito Carbonara has documented how Casciaro was subject to defamatory invectives from some fellow painters, who even accused the artist of passing off the work of others as his own. Casciaro seemed undaunted by this and, once established, continued to work hard regardless of his detractors.

Morelli, ‘radiant (solare)’ by character, worked from invention and not dal vero: ‘rappresentar cose non viste ma vere e l’immaginate all’un tempo’ (‘To represent things not seen but true, and imagined at the same time’) was one of his famous sayings. His orientalism exemplifies this, as it was the creation of his imagination and of work in his studio. There was a tremendous variety in his work, as well as an exuberant chromatic range. Notwithstanding his Romantic approach to art, Morelli was also open to all new innovations and encouraged an atmosphere of more friendly and sincere relations with the students. Palizzi, on the other hand, was an altogether more reserved figure, ‘schivo’ by temperament. Accounts suggest that he was completely different to Morelli and had different ideas about art. Palizzi was committed to the study of reality in assiduous detail. In spite of their differences, the two artists maintained good relations, although later Morelli was to portray himself as a man of wide experience and culture, which he compared to Palizzi’s simplicity. This was a condescension which possibly betrayed his own nervousness about Palizzi’s formidable talents.

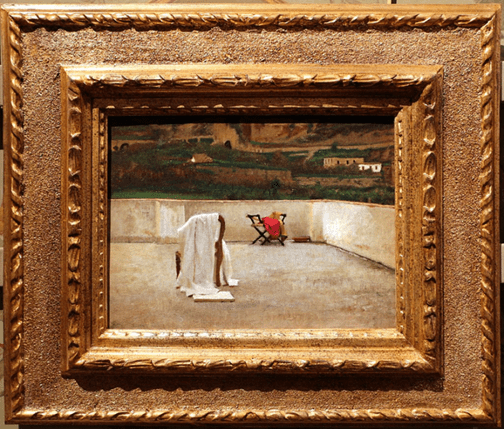

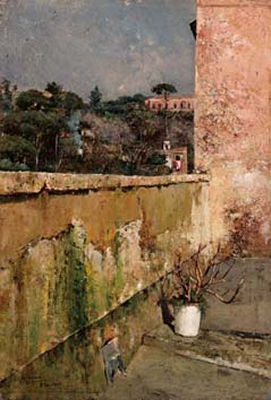

Domenico Morelli, La Terazza (1868) Gallerie d’Italia, Napoli.

(Credit: Wikipedia).

Filippo Palizzi – Effetto di luce in una strada di paese in salita, 1861 ca. (painting originally from Casciaro’s own collection).

(Credit: Farsettiarte Casa d’Aste.)

There is something interesting here too in the combination of these talented figures: Morelli a champion of sensuality, imagination and exuberance and Palizzi, a reserved individual with a serious dedication to his vision of truthfulness over imitation. Casciaro, as we will see, has a field of expression which navigates between these poles; his landscapes occupy places in a spectrum which ranges between naturalistic detail and poetic reverie.

Whether or not students had a progressive view of how they wanted to approach painting, overall, theirs was a traditional training. Training in the academy attended to the close study of form, of anatomy and disegno, and (notwithstanding what we have said about Lista’s progressive side) it still included studying from Roman and Renaissance casts to develop the ability to represent plastic movement and to work on the depiction of light and shade. (See Brizia Minerva in Lanzilotta (ed.) (2019)).

In spite of the innovative and exciting en plein air work of artists of the Scuola di Posillipo, like Pitloo and Gigante, and a long landscape tradition in Naples, some artists and connoisseurs of the nineteenth century still considered landscapes to be a secondary art form. For some, prestigious art was necessarily figural, historic, romantic and ‘realistic.’ Part of the reason that landscape art was considered inferior to historical and mythological scenes went back as far as the discourse of the Renaissance, which in turn was informed by the humanist interpretation of the classics. In this tradition, invention was considered intellectually superior to mere imitation.

In his choice to paint outdoors, Casciaro was working close to the spirit of The School of Resina (or The Republic of Portici, as Morelli ironically named it.) This was an anti-academic gathering of artists which, at one point, counted De Nittis in its number. Christine Farese Sperkin has argued that the school reached its fullest expression in its middle years when it demonstrated the following characteristics (and here I paraphrase her view). [In these years it comprised] the steady, extremely clear vision of the image and the precise rendering of every detail, all the way to the horizon line (which gives the same value, both in terms of design and colour, to all the elements) and the wide and articulated spatiality. The clear, crystalline light creates an atmosphere of timelessness and suspension. See (Picone Petrusa, ed. (2002)).

Federico Rossano, Campo di papaveri (1875).

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

Casciaro was also surrounded by talented contemporaries with whom he shared ideas and even residences; great artists such as Gaetano Esposito and Attilio Pratella. It is also important to note that he retained an interest in younger painters and included their works in his own art collection.

A pivotal moment for Casciaro came when he saw an exhibition of pastels by the artist Francesco Paolo Michetti, at the Promotrice Salvator Rosa of 1885. Michetti had been working with pastels since 1877, although his pastel works were often combined with tempera painting and he also used pastels for both preparatory purposes and completed works.

Francesco Paolo Michetti, A Hillside Path with Blooming Cherry Trees under an Overcast Sky, 1905.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

For Casciaro pastels became the dominant medium for his work, for numerous exhibitions and for an art market which responded enthusiastically to his production. Casciaro exhibited his pastels every year from 1891-1915 then, from 1915-1926 there was a pause, after which he picked up exhibitions with a high level of frequency until 1939.

In a wider cultural sphere, De Nittis had started to use pastels in Paris, often for portraits and figure groups. These studies were sometimes outdoors, sometimes in, but in all cases they gathered reflections, shades of light and lively surfaces. One example of De Nittis depicting a landscape in pastels is Lungo la Senna davanti alle Tuileries (1876 circa).

This is a meditation on a pale northern light, an autumnal or winter scene. Here, while the light is inevitably more northern than we would generally find in Casciaro, and the setting more urban, there is a similarly poetic mood and a similar predilection for the use of whites and greys to unify the composition.

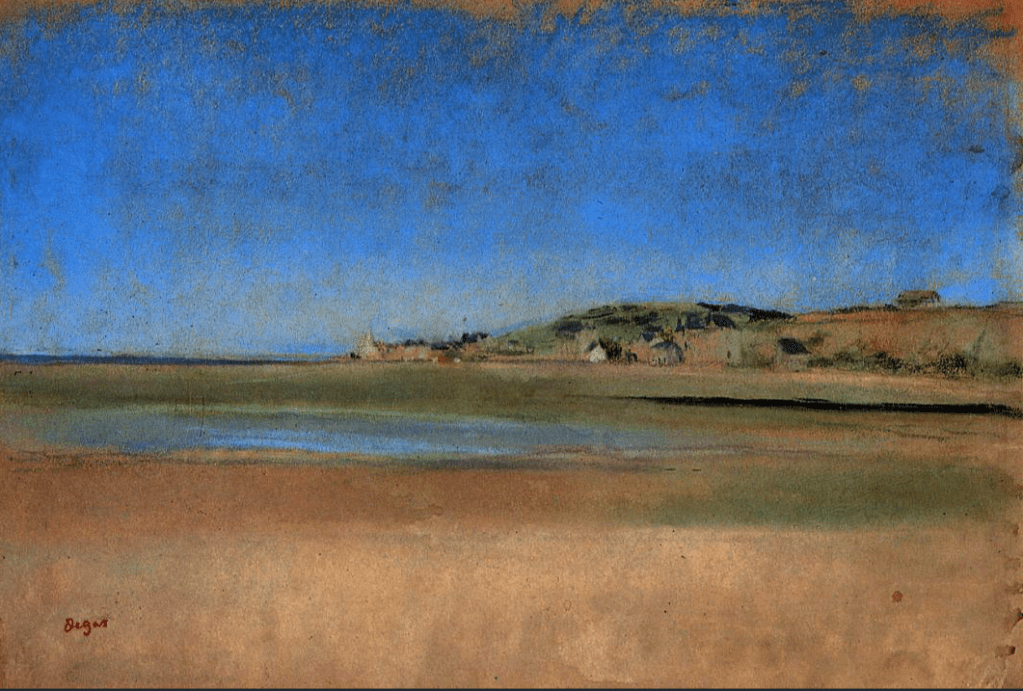

Degas—whose father was born in Naples and who visited family there on several occasions—worked with pastels for landscape subjects in both the 1860s and the 1890s. One example is Houses by the Sea (1869), a pastel painted on the northern coast of France, in Normandy.

(Credit: Musée d’Orsay.)

Also, we can consider this work: Edgar Degas, Beside the Sea (ca.1869).

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

These works present smoother, more distant scenes, characterised by lighter textural and compositional detail than we typically see in Casciaro’s oeuvre. That said, it’s important to acknowledge the breadth and diversity of Casciaro’s output—which, moreover, has yet to be fully catalogued.

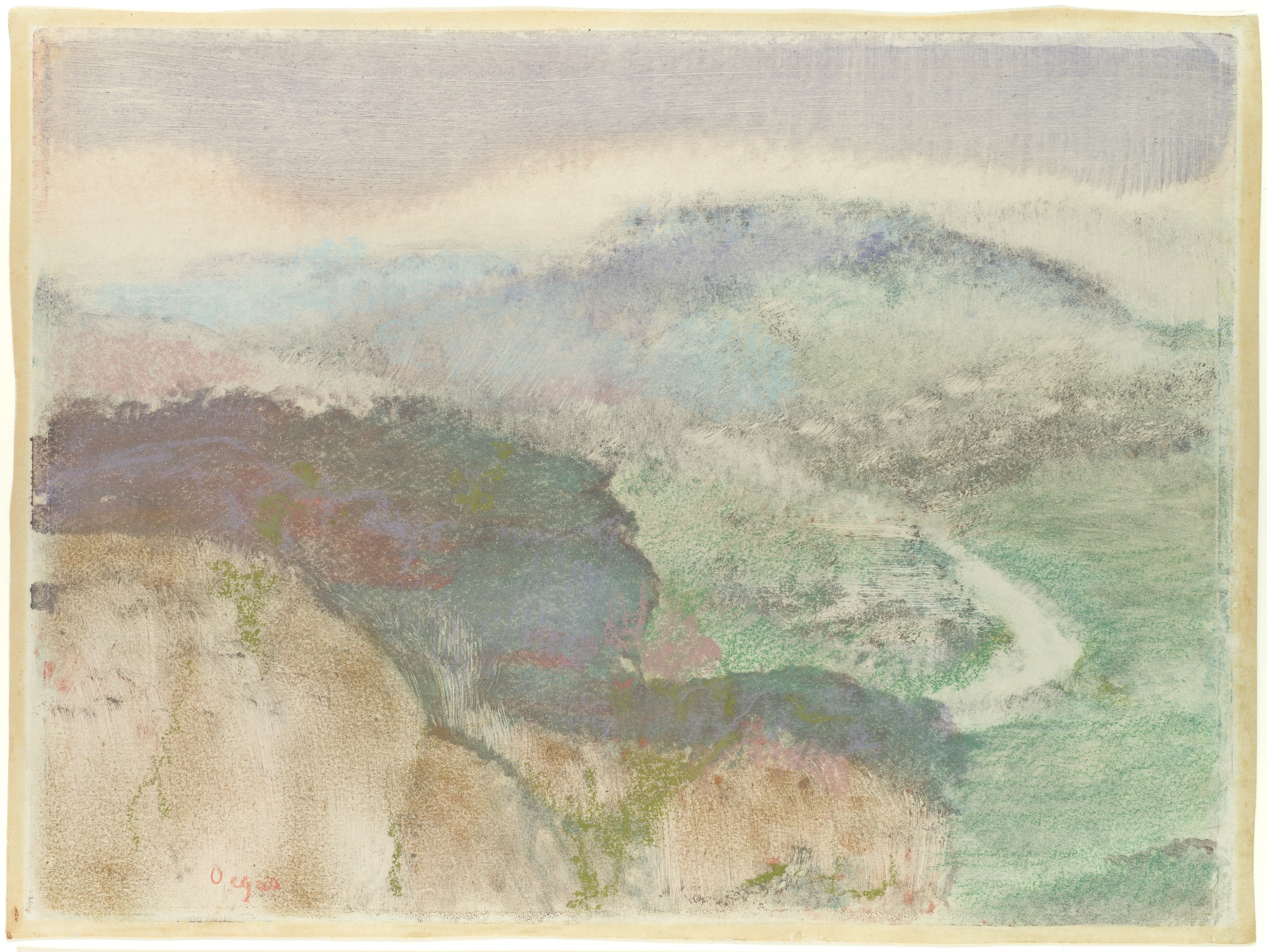

Degas’ landscapes of 1890 were even more different.

Degas, monotypes ca.1890, oil and pastel/pastel.

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/359362

(Credit: Metropolitan Museum.)

These were monotypes finished off with pastel. They were ‘pleasantly chimerical’ and border on the abstract. They were inspired by the synthesis of landscape impressions gathered by the artist as he travelled by carriage to the Burgundian estate of his friend Pierre-Georges Jeanniot. We know from correspondence that these were undertaken playfully and were seen to be a sure and simple way to earn some money. They were exhibited in the Durand-Ruel gallery in 1892. (For more on these monotypes, see Katie Hanson’s lecture from 2018: https://youtu.be/lUepMHPS2b8?si=25ozz2RnlIlUhxTD ).

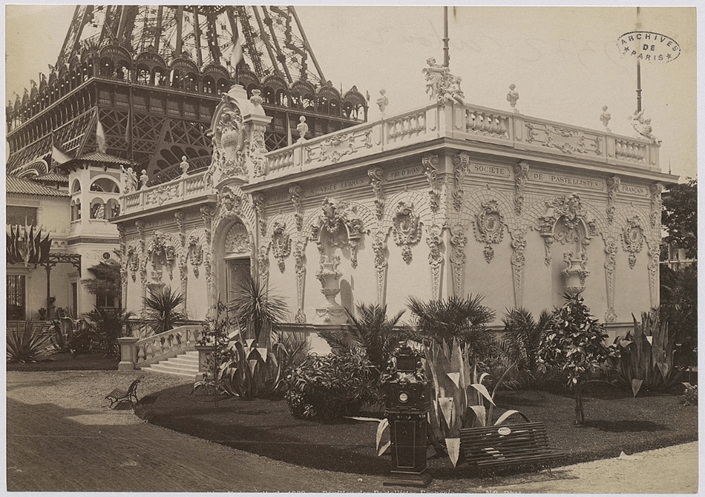

The importance of pastels as a medium in the nineteenth century is also illustrated by the fact that, on the 13th March 1885, The French Society of Pastelists was formed – they had an ornate little pavilion at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1889.

Exposition Universelle de 1889, Société des Pastellistes.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

As we know, while Casciaro exhibited widely, he painted closer to home. The demand for scenes of Naples was, of course, well established well before the second half of the nineteenth century when Casciaro began to exhibit his work: Naples and its coastline had long been a seductive location for landscape artists and their buyers (see Valente, 2009). The Bay of Naples, enchanted by the siren Parthenope, and cradled in the shadow of Vesuvius had long held a fascination for artists well beyond the confines of Italy. As an essential stop-off point in the Grand Tour and a place of fascination for famous northern literary figures such as Goethe and Nietzsche, its pull was well established. Grand Tourists and tourists wanted to take home mementos of the sun-drenched south. Prior to Casciaro’s studies of more intimate, less grand and overtly iconic, scenes – a shift towards more spontaneous landscapes had already taken place. The aforementioned talents of Pitloo and Gigante had moved away from large scale ‘horizontal’ landscapes, and the sublime and scientific depiction of volcanic activity, towards something altogether more personal and gently atmospheric.

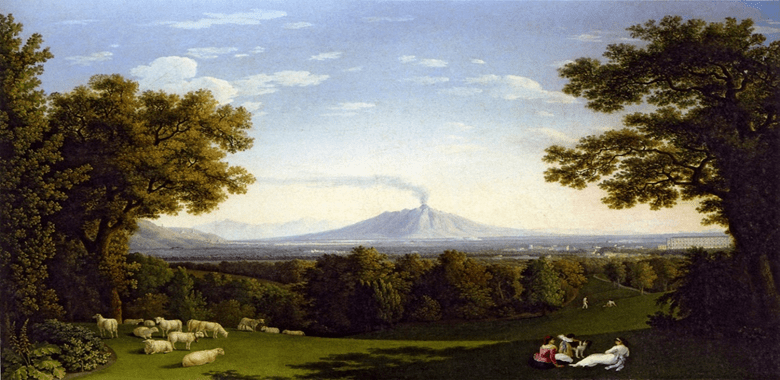

Jacob Philipp Hackert, Landscape with the Palace at Caserta and Vesuvius (1793). Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid. Note the predominantly idealised and broadly symmetrical landscape with repoussoir trees that almost act like stage curtains.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

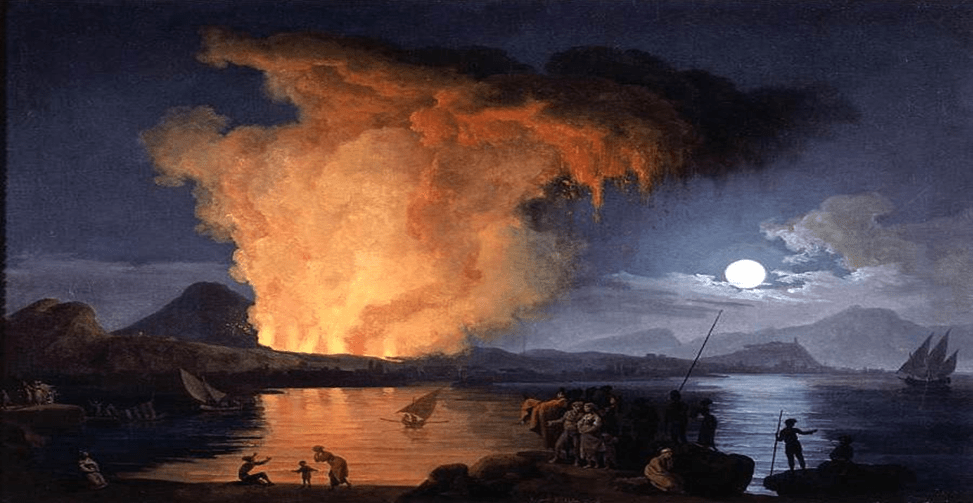

Pierre-Jacques Volaire, An Eruption of Vesuvius by Moonlight (1770s): a sublime and spectacular scene of Vesuvius erupting, at night.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

Anton Sminck van Pitloo, Vines at Báia (ca.1820-30) NG London.

https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/anton-sminck-van-pitloo-vines-at-baia

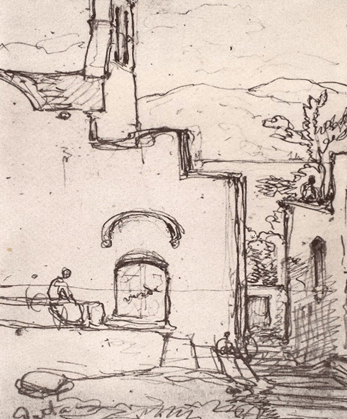

Giacinto Gigante, Casa delle Ancelle a Donnaregina (Vecchia Napoli), 1865. Gallerie d’Italia, Napoli.

In these two works, of Pitloo and Gigante respectively, note the shift from grand scenes to the unscripted and the fleeting. All this to the extent that, especially with landscape studies, it sometimes becomes difficult to name the location with any precision. We are a step closer here to Casciaro’s visual world.

Giacinto Gigante: Case a Gaeta.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons).

(There is of course is a substantial body of literature on the subject of Neapolitan landscape art as a seemingly endless list of artists were inspired by Naples. One could start with Causa Picone and Causa, 2004 and Valente, 2009 and readers in the UK could take a trip to the collection of Neapolitan paintings at Compton Verney in Warwickshire.)

The market that Casciaro was working for was different from those of earlier decades or centuries: he was making small-scale works for a labile market and not working to commission for select aristocratic patrons. Casciaro worked hard to produce scenes for exhibitions and he also attracted the patronage of the merchant Adolphe Goupil in Paris; this was subsequent to his success at the Paris Salon of 1892. (The Maison Goupil’s influence is often credited with helping bridge the gap between high art and popular culture, while also laying foundations for modern art marketing practices. It ceased operations in the early twentieth century.)

Details of a contract made with Goupil by Giuseppe De Nittis in 1872, illustrate clearly the pressures of the interface between art and commerce: De Nittis was required to respect the following standard, namely that the monthly payments in actual money must be matched by the entry of works of a minimum value of at least double the amount advanced by the merchant. In fact, De Nittis broke his contract in 1874 due to Goupil’s increasing demands to cater for the fashionable tastes of a rising bourgeois market. I have found no evidence of Casciaro facing similar pressures but it is possible, if not likely. (On De Nittis and Goupil, see Stefano Bosi’s contribution in Martorelli (et al.) (Genova, 2017)).

So, Casciaro was committed, to a large extent, to what lay between the iconic images. Even when he does depict the Faraglioni of Capri, or Vesuvius, the scene is far from being a grand historical sweep, a picture postcard, or a schematic topographical study.

Casciaro was working in an artistic climate suffused with a, slightly paradoxical, spirit of realism which had its literary correlative in the work of the philosopher and historian Francesco de Sanctis (1817-1883). De Sanctis thought that art should not just be the product of individual genius, but the expression of a historical and cultural moment: ‘La forma non e un’idea, ma una cosa.’ He also asserted that it was ‘reality that generated the ideal’, that is to say, without an attention based on reality there could be no ideal or sense of transcendence. Moreover, if we take two of the main aesthetic principles of this era, verismo and realismo we can also see potential for tension, or contradiction. Realism requires a naturalistic representation of events, while verism requires a truthfulness to the spirit or the emotion within a scene and the latter might require a distortion of the former. In Casciaro’s landscapes we see both elements at play – they are recognisable as true to life (to varying degrees) but, simultaneously, they are often gently untethered from time and edging towards a state of reverie.

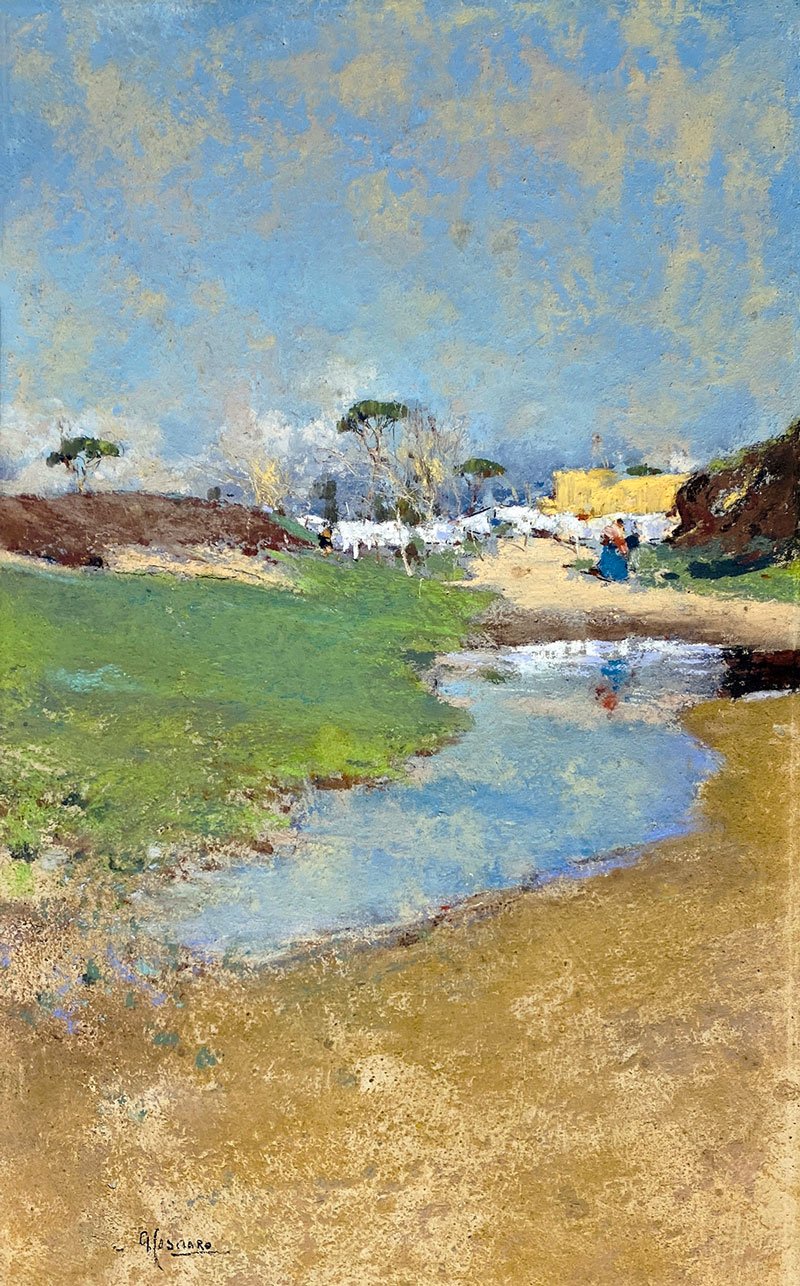

Giuseppe Casciaro, La Lavandaie (1895). This socially realistic scene which nonetheless retains a poetic lightness.

(Credit: Mark Murray.)

https://www.markmurray.com/giuseppe-casciaro-paintings-for-sale

In all events, Casciaro’s moment and place was found in his local landscapes and, towards the end of his career especially, his chosen places and moments contrasted with the fast march of urbanisation and industrialisation. Nusco, in Irpinia, was one such place.

Giuseppe Casciaro, Sorge la luna a Nusco, oil on canvas (ca.1924).

(Credit: Mutual Art.)

His home region of Salento, especially Castro and Ortelle, were also the subject of his study. In all events, these works were never merely iconic painterly citations of famous landmarks. Each en plein air study conveyed something very specific – these were fleeting moments, in quiet rural spaces, with their own air of truthfulness and spirit of spontaneity.

As landscapes, they could not be tagged to noteworthy figures of his time, as portraits could. Nor did they have a traditional historical or mythological story to tell, through which they could be compared to famous precedents, or form material for intellectual debates. While this observation might seem facile, one of the perennial guarantees for an artist’s status and memorial was through an alliance with intellectual culture.

As mentioned earlier, part of the reason that greater prestige had been given to historical or mythological subjects was that they could be related to literature. Moreover, with such subjects, educated admirers could puzzle over, and debate, possible enigmas or new interpretations of a long-established scene. While no one can deny the elevating experience of contemplating a pure representation of landscape, it can be hard to develop a varied and compelling mode of discourse for the experience. One can quickly fall into cliches which, however apt, seem to fall short through their recurrence. We will later see that the praise that Casciaro received from critics and journalists, while abounding in just enthusiasm, seems limited to a relatively small range of metaphors.

Whatever the confines of the written commentaries, Casciaro’s works were charged with his own sensibility, with his influences, and they varied according to light, location and mood. Casciaro had many influences to draw upon, but he did not belong to a specific school and did not have a narrow manifesto. His works were hard to pin down and entering, as they often did, a dynamic private art market in which they passed hands frequently, they are difficult to catalogue. What is more, they inspired a prolific output of forgeries.

Casciaro was industrious and much praised in his time but, perhaps one of the reasons he is cited as a moral painter, is that (especially with hindsight) we can see that he was not working in a way that guaranteed a legacy or courted attention for anything but the works themselves. Casciaro’s truthfulness to his own vision, his decision to remain in southern Italy (rather than relocating to France) together with his adherence to a certain continuity within innovation, may have contributed to his subsequent neglect.

Added to this we can add the more general fact that the Italian Ottocento as a whole has been marginalised – not least as Longhi’s ‘stupido secolo.’ Infamously, Longhi condemned nineteenth century art in the following summary: ‘The century that spans from the 1800s to the 1900s is the stupid century, the century of intellectual dishonesty, of a lack of passion, and of that scarcity of critical spirit which characterised our art.’

While Casciaro stands apart for many reasons, he is one of a number of highly talented artists who worked in Naples at the end of the nineteenth century and into the early twentieth, all of whom have risked, or still risk, a sort of unintentional damnatio memoriae. Casciaro lived to be eighty and his output was extensive in all respects; in relation to the quantity of works he completed, the number of exhibitions he took part in, and the span of time that his career covered. While past and ongoing studies by Vito Carbonara are connecting Casciaro’s styles and subjects to specific periods, I shall attempt a very general overview here of the variations we are likely to discover in viewing a range of Casciaro’s pictures for the first time.

In terms of colour, he could introduce a range that is intense, emotional and vibrant. (Some commentators have referred to him using a kind of heightened realism, a sort of realism that while ‘transposed to another level’, doesn’t enter into the territory of the symbolist movement.)

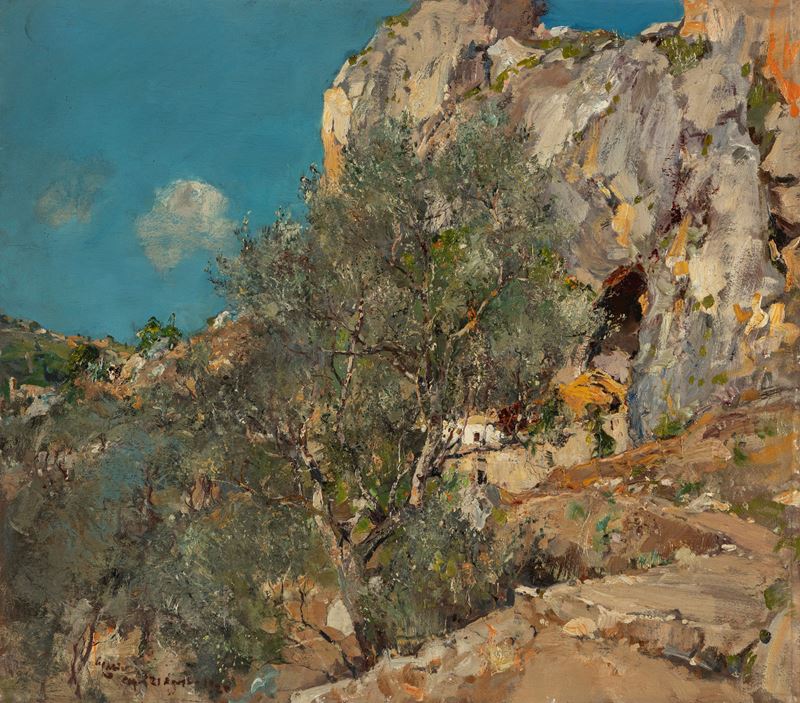

Giuseppe Casciaro, Landscape in Capri (1925).

(Credit: Stephen Ongpin, Fine Art.)

In another instance, Casciaro’s range might be more muted, with contrasts reduced by a pervasive use of, for example, a pearl grey. He would use the technique of ‘enveloppement’ in which the image is wrapped by a continuity in colour, through the blending of tones and through gradual transitions between light and dark. Conversely, in other works, contour or outline might be far more clearly defined.

Giuseppe Casciaro, Sotto il Portico (1926).

(Credit: Mutual Art.)

Note the white/grey blending of colour transitions.

Casciaro’s use of white was highlighted by Bice Viallet in around 1917-1918 – Viallet considered them Casciaro’s ‘joy’ and noted various ways in which they were used. Faint, light and soft whites were used to capture snow and clouds, while a chalky and arid white would be used to capture the surfaces of walls and buildings as they reflected strong sunlight. Viallet cited the depiction of a church in Capri as an example of the latter. (See Carbonara, 2022).

Giuseppe Casciaro, Path through the Thickets, Spring (1897).

(Credit: Artnet.)

An important line of approach in coming closer to Casciaro’s work is to consider the medium that he used. From Vito Carbonara’s research we know that Casciaro used a rich and oily pastel which comprised a thick stick of highly concentrated colour, held together with a minimum concentrate of binder. We also know that he loved to make these himself and it is evident that, with them, he could achieve brilliant tones, realise smooth strokes (he also used his fingers in the application) and create a type of sfumato effect, as well as being able to create energetic lines and define clear boundaries when he wished to. As well as preparing his own pastels, Carbonara has discovered that Casciaro did not like to use manufactured card but rather took a very strong grey card which he then prepared with a thin layer of whiting or clay, dissolved in water with 0.2% of sublimate (mercuric oxide, a toxic compound used in art and preservation.)

One frequently cited shift in the style of the French impressionists was a move away from chiaroscuro. This observation could reasonably apply to Casciaro’s pastel, but it is important to say that while pastels may have reduced the capacity for tonal modelling, they allowed for great subtleties in chromatic modelling and the exploration of colour as structure. That is to say, in pastel composition, where one might lose a capacity for subtle gradations of light and dark (something possible with great nuance and subtlety in oil) one could still achieve light changes through the use of different densities and properties of colour, through changes in hue and saturation.

Giuseppe Casciaro, Il laghetto di via Forìa (1900). Private collection.

Chromatic modelling in pastel: note the muted shades of the reflections in the lake.

Further to this, a consideration of even three core pastel techniques, helps us to see how a pastel artist like Casciaro could employ layered colours, to different effect. The blending, or rubbing together of two pastel colours could produce subtle nuances of colour. The application of a pastel layer in a loose, uneven or scribbled manner – scumbling, could be used to create a rough, opaque, textured effect, which would allow underlayers to show through. In a similar manner, the overlay of a thin transparent layer of pastel, a glaze, could allow light to pass through layers, in a more smooth and unified way, creating a sense of luminosity and depth. The repertoire of the medium therefore invites its own possibility for the mastery of colour and texture. We should also note that Casciaro was adept at using a quite thin and ‘nervous’ line to depict, for example, the movement of waves.

The juxtaposition of these two works by Casciaro, of A Summer Day and Castro Marina, offers a visible measure of the different finishes that are possible when working in pastel.

(Image credits: Mark Murray/ Blindarte.)

We have a lively recollection of Casciaro’s mastery of pastel technique in a testimony made by the Neapolitan artist Carlo Siviero:

‘Casciaro’s box of pastels is impossible to describe: a pinch of grey stones, uniform, small pieces no bigger than a bean; in that uniformity of ash, the tone of coral red or the intense blue of turquoise stood out. Casciaro, without looking for the colour, could feel it by touch, recognizing it by the shape of the pastel piece: he would sink his fingers into the box and, from all that grey, pull out, with certainty, the colour he needed. With the pads of his fingers, he kneaded, fused, and barely touched the surface of the painting, and not infrequently, he would strike it with the palm of his hand… Then, Siviero continues… once a work had been finished, he would move a few steps away from the place he was and, through a little rectangle of card, size up a new subject. With the dull and powdery material he handled, he was able to fully capture the crystalline transparency of the sky, the oily sheen of the sea, the glazed green of the pines, the solid compactness of the rock.’

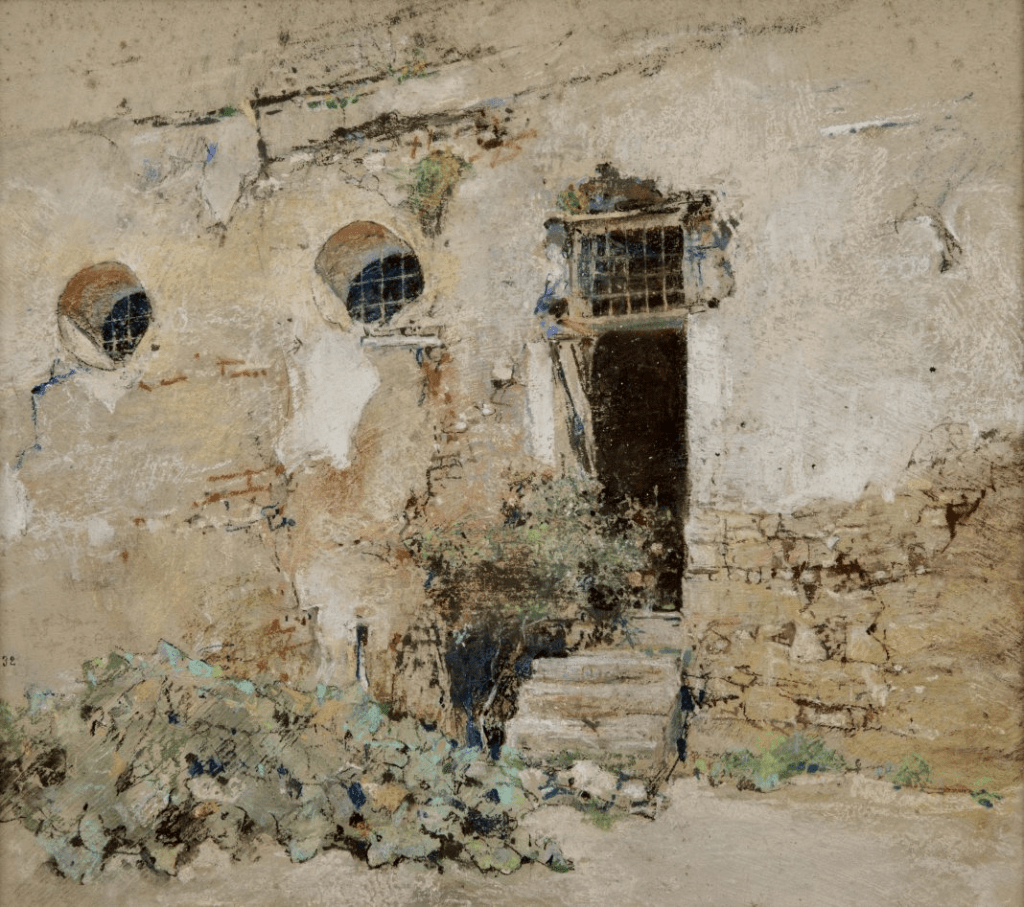

The composition in Casciaro’s works might focus on purely natural scenes, or it might incorporate rustic architectural features, creating a contrast between the suggestive impressions of nature and straight architectural lines. Rustic buildings would also allow for a close study of the surface texture of stone, a common focus in the work of Filippo Palizzi.

Filippo Palizzi, Over the Wall (1865) Private collection.

(Credit: Wikipedia).

Casciaro, Porta con grata (1932) from the Signum collection, Lecce.

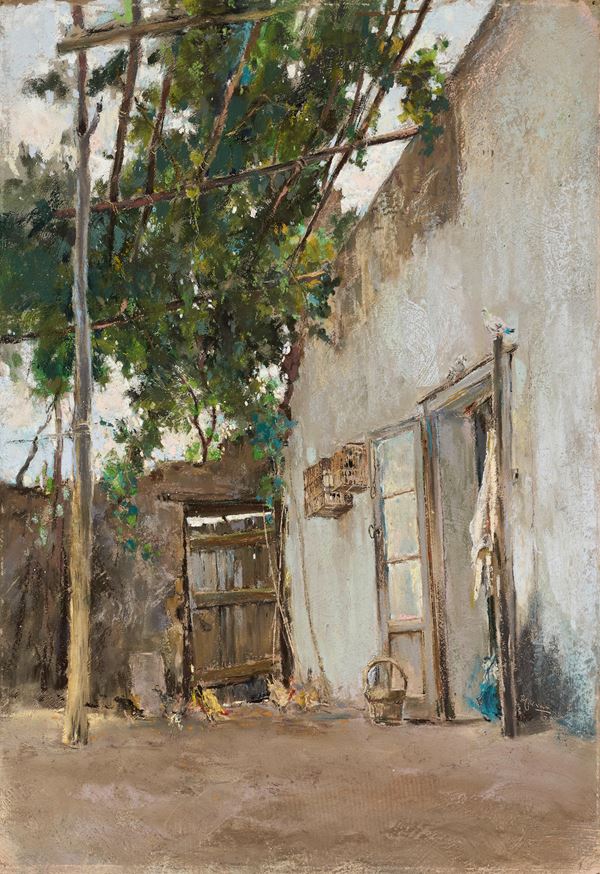

The linear alignments in buildings, colonnades, or pergolas could work to create depth of field, as well as suggesting a steady time-worn reality in which activity seems to have been suspended.

Giuseppe Casciaro: Rustico con pergolato.

(Credit: Farsettiarte.)

In other compositions, a transverse ‘terracing’ of colours or pictorial planes could create different type of effect – one that invites the eye to track up through the consecutive levels in the image.

(Credit: Mutual Art.)

This pastel study, made by Casciaro in Castro (1931) has a receding line of rocks which creates a depth of field. In addition, the viewer is invited to track upwards through stratifications in the slope. Simultaneously, the composition has depth, in the foreground, as well as a kind of flatness in the upper half, which recalls Japanese prints.

Casciaro’s composition is sometimes close while, at other times, there are expanses of lightness, a feeling of space and an airiness. At times, we are invited to contemplate wide visions of the sea, scenes open to the elements which offer us a sense of freedom.

Scene of Capri, 1906 and Terrazza a Capodimonte 1887.

(Credit: Mark Murray/ askART.)

The images above illustrate Casciaro’s compositional range—from a seascape capturing light effects on a vast expanse of water to a detailed textural study of a terrace, marked by modern, cropped lines of sight.

How do we fare with other labels? Casciaro’s work can tend towards post-impressionist abstraction, with his use of a bold and dense realisation of outline, particularly in the representation of large rocks and cliffs. However, if we set his scenes beside a work of Cezanne’s, we can see where Casciaro adheres to his own limits, where he chooses to hold true to his own style.

(Credits: Finarte / Wikimedia Commons.)

Casciaro’s oil study of Capri (1920) can be compared to Cezanne’s Rocks at L’Estaque (1879-1882). The rocks in Casciaro’s work verge on a two-dimensional plasticity; although they retain some naturalistic depth cues, they are rendered in thick impasto that contrasts sharply with the finer treatment of the trees and clouds in the centre and left of the composition. In Cézanne’s work, by contrast, the flatness of the picture plane is more pervasive and pronounced. His use of colour and faceted brushwork further distances his approach from Casciaro’s.

Equally, while there are impressionistic elements to Casciaro’s work, he does not push them towards presenting a picture surface that is destabilised by the effects of light.

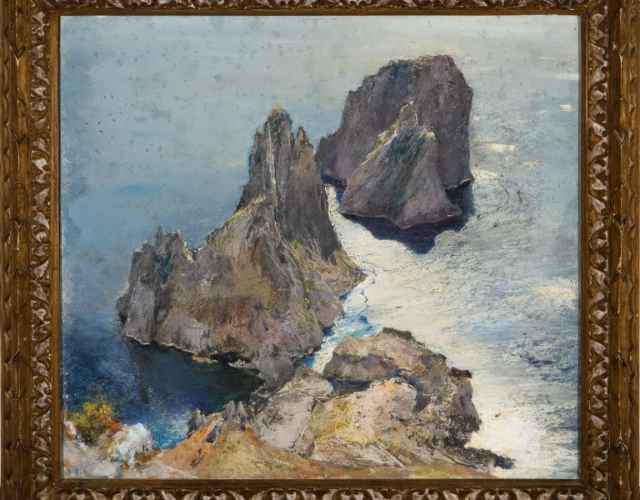

The first work below is Cascario’s pastel of the Faraglioni at Capri, from the Galleria d’Arte Moderna Ricci Oddi in Piacenza. Beneath that we have one of Monet’s studies of Les Pyramides de Port-Coton. While both works capture an ephemeral moment with mastery, the sharper and more planar naturalism of Casciaro’s pastel contrasts with the stippled and painterly brushwork in oil by Monet.

Faraglioni at Capri, Galleria d’Arte Moderna Ricci Oddi.

Les Pyramides à Port-Coton, Claude Monet (1886).

(Credit: Wikimedia)

Compositionally, Casciaro’s works can err towards simplification, without ever tipping towards abstraction or departing entirely from naturalistic representation.

(Credit: artnet.)

This study of Casoli (1895) offers us a pared down composition using a simple zig-zag of diagonal vectors. It is a study of nature that has just the suggestion of a solitary human presence, beneath a tree on the left. There is bright light coming from the left and creating strong shadows from the trees. The overall scene is peaceful with just a suggestion of human presence making a mark on the landscape – there is a quarry and what could be houses on the distant horizon. There are no intrusive ruptures from the landscape tradition and nature takes pride of place.

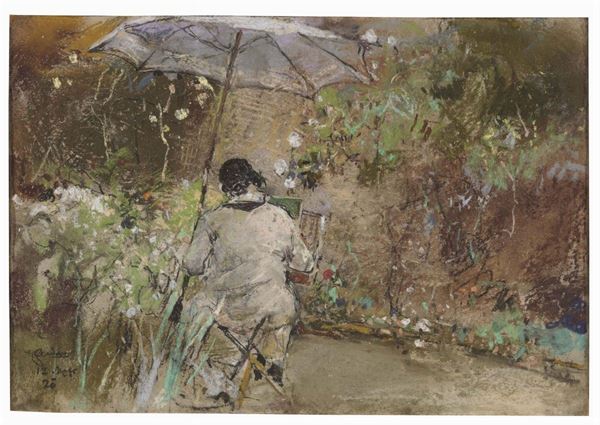

Throughout his career, Casciaro conveyed a sense of freedom and vitality, continually striving to capture the ever-changing natural scenes unfolding before him. Within the broader scope of his study of nature, a variety of distinctions can be made—for instance, while he depicted wild, untamed landscapes, he also turned to more intimate subjects, such as the following work from 1925.

(Credit: Farsettiarte.)

After viewing a series of his works in quick succession, we might be left with the impression of scenes of pure nature. However, figural elements play their part in his oeuvre, such as his pictures of women washing laundry in a river or portraits of his wife, self-absorbed in quiet activity. Vito Carbonara has noted that people play an increasingly important role in Casciaro’s paintings made in Nusco in 1924. Here figures offer us an emotional engagement with living processes and moments, such as in La Fiera di Sant’Amato, o Fiera a Nusco (see Carbonara 2022, p. 139).

Another notable element of variety in his legacy comes from his still life studies, most of which were made in his later years. Some of this still life arguably suggests his age and, in practical terms, the works must have offered Casciaro an opportunity to continue painting without the physical demands of working en plein air. Whatever the case, they bear testament to his depth of culture, as classic still life works by artists such as Ruoppolo were in his collection. The example below shows us a still-life with vases of flowers, including what looks like a small maiolica pharmacy jar, presumably from his collection.

(Credit: Capitolium Art.)

It is arguable that Casciaro’s landscapes echo the influences of Japanese art, if only indirectly and perhaps through an intuitive assimilation of the trends of his time. In some of his landscapes, there are traces of Japonisme in the way in which trees and plants stand out against the sky and in the use of flattened space and bold colour. The following works offer us an interesting comparison.

Giuseppe Casciaro: Stradina nei pressi della costa (1904).

(Credit: Finarte.)

Utagawa Hiroshige (1797 – 1858): Yamato Province: Yoshino, a Thousand Cherry Trees at One Glance.

https://harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/210229

Moreover, whenever we look at his seascapes, we should recall that he owned a number of marine studies by Turner. The illustrations below show both artists engaged in a similarly visionary exploration of how colour can dissolve the boundaries between a subject and its emotional resonance.

Casciaro, Marina con pescatori.

(Credit: Arcadia, Casa d’Aste.)

JMW Turner, Sea and Sky, English Coast (c.1830–45).

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-sea-and-sky-english-coast-d36228

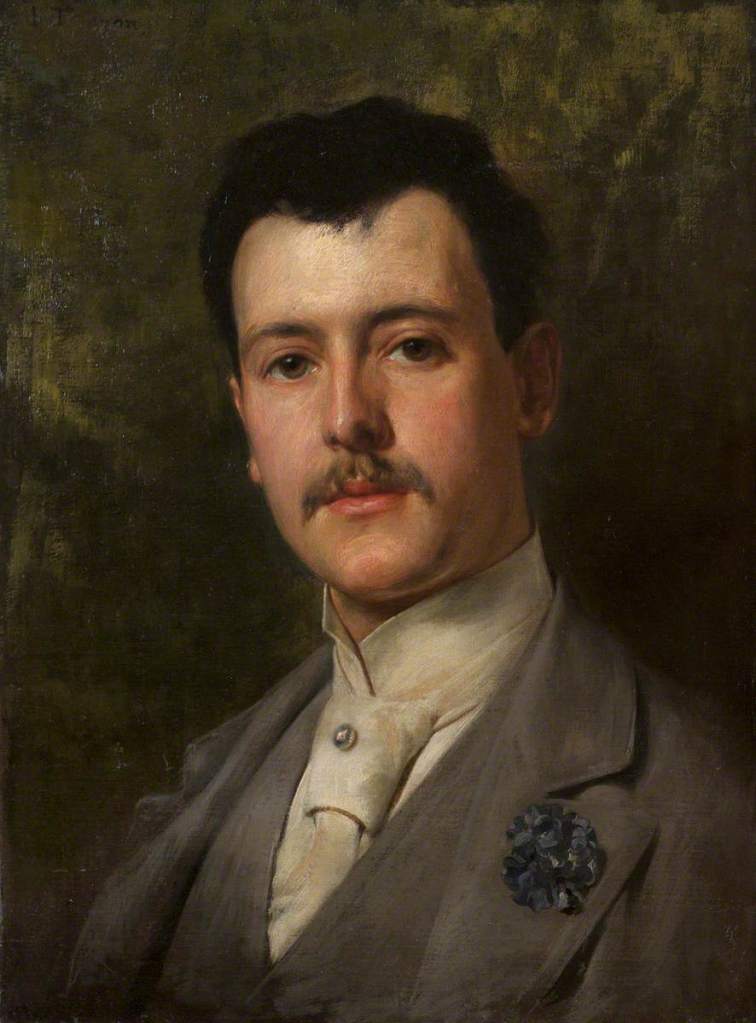

While the focus of this introductory piece is to raise awareness of Casciaro’s now neglected talent, it is equally important to re-state what an important figure he was in his own time. To the indications of this mentioned above, we should also mention the fact that he was appointed a teacher to Italian royalty: in 1906 he became the painting teacher of Queen Elena of Montenegro, the queen consort of King Vittorio Emanuele III; a woman who was beautifully depicted by Vincenzo Caprile in this portrait of 1899.

Vincenzo Caprile, Elena del Montenegro, principessa di Napoli (1899) Gallerie d’Italia, Napoli.

(Credit: author’s photograph).

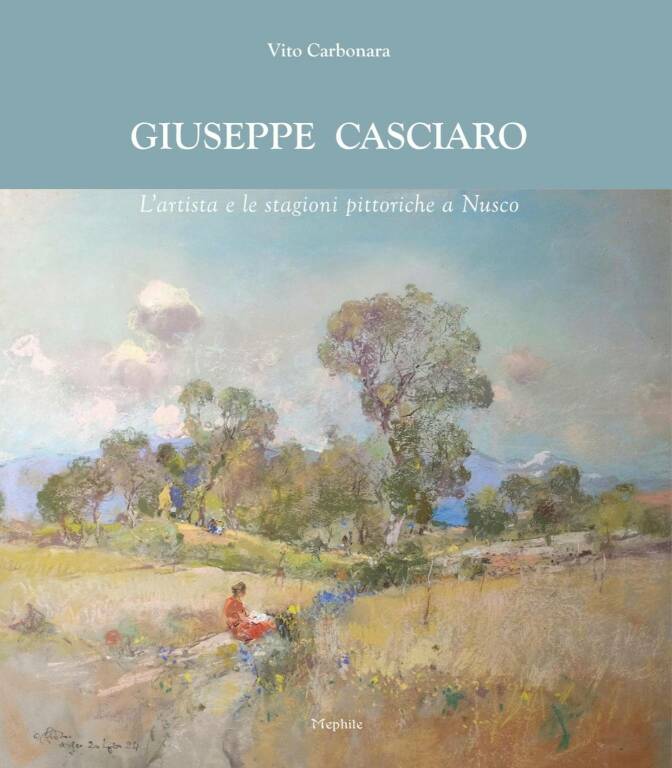

Prior to 1906 (the same year as an important exhibition in Milan which they attended) the royal family were conversant with Casciaro’s work and already had works by him in their collection. They were in fact part of a wave of demand for his landscapes. Vito Carbonara’s book ‘Giuseppe Casciaro: L’artista e le stagioni pittoriche a Nusco’ has established a formidable documentary and interpretative foundation which, among many other considerations, collates reviews and articles written in response to Casciaro’s many exhibitions. These reviews are highly informative as they reflect the artist’s wide-ranging appeal and his enthusiastic reception.

There are themes that constantly reappear in the praise of his art. There are, for example, frequent comments on the luminosity of his works. They are seen as both real and true, as well as poetic and evocative. The variety of moods conveyed through his landscapes is seen to be wide ranging; from idyllic, bright and expansive, to introspective, melancholic and crepuscular. The elusive effect of his pastels on a viewer’s emotions is also suggested though comparison to music and poetry. (Casciaro had eight chalk medal portraits of major composers in his collection, which at least suggests that music may have, in fact, been important to him.) Beyond this, each study is often seen as a deeply personal work and Casciaro is often portrayed as a moral figure who is true to himself and who is industriously charting his own course. One of my favourite, and less formal, assessments of his talent comes from Antonio Mancini, who reportedly stated:

“My dear Peppino, you are a Vesuvius! But instead of erupting fire and ash, you spew pearls and turquoise, emeralds and rubies, along with a shower of roses.”

We might choose to read an accidental insight in Mancini’s effusive and complimentary metaphors, as Casciaro’s house-museum-atelier, for such it was, contained a significant collection of material culture – art objects of various kinds. He had objects in maiolica, in glass, in silver, as well as fabrics. These also must have informed his sensibility for representing colour, light and texture.

Casciaro’s legacy can also be seen through the work of his students. His academic roles were significant and he was sought after as a private teacher, especially after being chosen as the teacher of Queen Elena in 1906. What is more, two of Casciaro’s four children developed as painters, as illustrated by an exhibition held in Rome in 2004, curated by Cinzia Virno. His daughter Carolina (1895-1978) and his son Guido (1900-1963) both began their artistic studies with their father and, to varying degrees, his influence can be seen in their works. Carolina’s style was closer to that of her father and it demonstrated close fidelity to the direct study from nature and many (but not all) of her works were on a small scale.

Carolina also demonstrated the same decisive strokes as her father. Both Carolina and Guido showed a preference for oil as a medium but Guido became freer in adopting his own style. He sometimes did works on a large scale, he applied himself to figure painting, as well as landscapes, and he tended to transform the scenes that he portrayed. At the same time, Guido resisted the pressure to join contemporary movements, such as Futurism. On one of his works, Marina con Cabine (Il porto di Castro) above his signature, in the bottom right-hand corner of the work, he wrote VIVA IL NOVECENTO/ ABBASSO IL FUTURISMO. Quite clearly, this epigraph affirmed a progressive attitude to art, while repudiating the constraints of a trend. The family entered their works together in Avellino in 1932, as part of the first Irpinian art exhibition: together they took up most of Sala 1, presenting 23 works in total. (See, Virno, C., I Casciaro: Giuseppe, Carolina e Guido. Roma, 2004).

While Casciaro undoubtedly guided countless students in the course of his long career, we can here look at a sample of four: two from Italy and another two, from England and America respectively. Guido di Renzo (Chieti 1886, – Napoli, 1956) produced landscapes, portraits and still-life studies.

https://artsupp.com/it/artisti/guido-di-renzo

Another talented artist, from Salento, Rita Franco (Lecce 1886 – Napoli 1985) produced pastel works of great sensibility which demonstrated that she was continuing the tradition of her teacher.

Credit: https://www.valerioterragno.it/artisti-salentini/106-franco-rita

Francis Edouard Chardon (Calcutta 1865 – Llandudno 1925) was an English painter of landscapes, portraits and still-life paintings who bequeathed his home in Llandudno for the enjoyment and education of the people: Rapallo House is now the site of Llandudno Museum.

Credit: https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/francis-edouard-chardon-18651925-181163

Albert Sheldon Pennoyer (Oakland 1888 – Madrid 1957) was an artist who worked in pastel, gouache, watercolour and oils. He worked on principally on portraits and landscapes of various scenes. While serving in the American army he was also one of the Monuments Men in WWII, documenting their activity in Italy with a Leica camera.

Credit: https://americanart.si.edu/artist/sheldon-pennoyer-3756

I hope that this brief article is sufficient to provoke readers into their own research into the work of Giuseppe Casciaro and the others artists cited above. At the time of writing, there is guidance about where to view Casciaro’s works listed at the end of the Italian Wikipedia entry for him. Moreover, for further detail on where to find works, the reader can refer to pages 175-176 of Vito Carbonara’s book (Avellino, 2022), this is an excellent resource and we can expect to see more from him on Casciaro in the course of time. (Please note, it is always worth checking with museums before taking a trip, as displays can change.)

Producing these articles requires care, time, research, and resources. Contributions to help sustain this exploration would be greatly appreciated.

https://donorbox.org/inner-surfaces-resonances-in-art-and-literature-837503

This study owes a significant debt to the work of others, and I have included a bibliography to acknowledge that debt. My primary aim in assembling this material is to raise awareness of this gifted artist—particularly among English-speaking readers, who are unlikely to have encountered Casciaro before. I sincerely hope that those with some knowledge of Italian will be encouraged to explore the original sources and the work of the authors cited. My special thanks go to Vito Carbonara and Cinzia Virno for their generous help and support. All errors and infelicities in the text are entirely my own.

You Tube has an enjoyable video of works by (and presumably attributed to) Casciaro. (It is always worth recalling that Casciaro’s popularity led to people forging his works.)

Bibliography

Bellenger, S. (ed.) Napoli Ottocento. Roma, 2024.

Benzi, F. (et al.) Francesco Paolo Michetti, catalogo generale. Milano, 2018.

Brown, M., Francesco de Sanctis: The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol.32, No4 (Summer 1974) pp.477-492.

Causa Picone, M. and Causa, S., Pitloo: Luci e colori del paesaggio napoletano. Napoli, 2004.

Campopiano, P., Giuseppe Casciaro. Treviso, 1999.

Caputo, R., Giuseppe Casciaro. Napoli, 2007.

Caputo, R., La Pittura Napoletana del II Ottocento. Sorrento, 2017.

Carbonara, V., Giuseppe Casciaro: l’artista e le stagioni pittoriche a Nusco. Avellino, 2022.

Carrera, M. (et al.) Antonio Mancini/ Vicenzo Gemito. Milano, 2023.

Cassese, G., Giuseppe Casciaro: un profilo europeo nella storia dell’arte e del collezionismo tra Ottocento e Novecento, in Depositi di Capodimonte, ed. Romano, C. and Tamajo Contarini, M. (Napoli, 2018).

Denvir, B., The Impressionists at First Hand. London 1987 and 2023.

Di Giacomo, P. C., Giuseppe Casciaro (1861-1941). Bologna, 1994.

Fiore, A and Russo, M. (eds.) Giuseppe Casciaro 1861-1941, Privato. Lecce, 2023.

Lanzilotta, G. (ed.) Incanto partenopeo. Guido Di Renzo, Giuseppe Casciaro e la comunità artistica del Vomero nella prima metà del Novecento. Bari, 2019.

Martorelli, L. and Mazzocca, F. (eds.) Da De Nittis a Gemito: i napoletani a Parigi negli anni dell’impressionismo. Genova, 2017.

Picone Petrusa, M. (ed.) Dal Vero. Il paesaggismo Napoletano da Gigante a De Nittis. Torino, 2002.

Valente, I. (ed.) Il Bello o il Vero. Napoli, 2014.

Valente, I., I luoghi incantati della sirena nella pittura Napoletana dell’ottocento. Sorrento, 2009.

Virno, C., I Casciaro: Giuseppe, Carolina e Guido. Roma, 2004.

Virno, C., La storia di una grande amicizia in un nuovo inedito ‘Ritratto di Giuseppe Casciaro’ di mano di Antonio Mancini, in About Art Online, ed. P. Di Loreto (Roma, 2025).

Virno, C. (ed.) Vincenzo Gemito: la collezione. Roma, 2014.

Virno, C., Antonio Mancini, catalogo ragionato dell’opera 2 voll. Roma, 2019.

Schettini, A., Giuseppe Casciaro. Napoli, 1952.