Pitloo, portrait by Pieter van Hanselaere (c. 1814). Source: Wikipedia.

Even if one were to grant Pitloo only what is evident in his redemption of landscape from the servitude of mannerism and convention, the arts, newly guided toward a beauty drawn from the true, would owe him immense gratitude. But there is more. Pitloo took on the role of an almost creative force rather than merely a reformer of the arts among us.

Pasquale Mattei, Cenni Biografici del Cav. Antonio Pitloo, in “Poliorama Pittoresco” (1860).

On 1 March 1803, Pitloo began his formal education in Arnhem under Hendrik Jan van Amerom (1777–1833). While a member of the local Society of Art Scholars, he progressed rapidly, and in 1807 he was awarded both a first prize and a silver medal for drawing. On 22 July 1808, he received the pensionato di Parigi from Louis Napoleon, King of Holland and brother of Napoleon Bonaparte, a royal scholarship that enabled him to continue his studies in Paris under official patronage.

Self-Portrait of Van Amerom with Wife and Young Son (1804)

(Credit: Wikipedia.)

Pitloo trained and gained experience from other European centres before settling in Naples: from 1808, he spent three years in Paris, where, thanks to the grant from Louis Bonaparte, he briefly studied with the architect Charles Percier before turning decisively towards landscape painting. By 1811 he was in Rome, moving within Dutch artistic circles and knowing painters such as Abraham Teerlink, Hendrik Voogd, and Martin Verstappen. His talent had thus brought him notable patrons, including the aforementioned Louis Bonaparte and the Duke of Berwick.

(Credit: Web Gallery of Art.)

By 1815, Pitloo had definitively moved to Naples. He had travelled there with the Russian diplomat Count Grigory Vladimirovich Orlov (1777–1826), an art connoisseur and writer, and remained in the city for the rest of his life, dying of cholera in 1837 at the age of forty-seven. Naples, of course, was a major stop on the Grand Tour and a magnet for European artists. From the late eighteenth to the early nineteenth century, painters from across Europe worked there in large numbers. Notable examples include Joseph Wright of Derby, Hackert, and Vernet in the later eighteenth century, and Catel, Michallon, Corot, Turner, Dahl, Rebell, Huber, and Carus in the early nineteenth.

While Pitloo resided in Naples from 1815, he made return visits to Rome, and we also know that he travelled to Sicily and Switzerland. This is documented by a series of drawings held in the Gabinetto Nazionale delle Stampe e Disegni in Rome. The workshop of Verstappen in Rome was certainly a point of inspiration and orientation for him; its importance is suggested by a letter he sent to his mother on 8 December 1813 (or possibly 1814). In this letter, he states, in italics, that Rome is a useful city for painters.

In 1820, Pitloo married Giuliana Mori, sister of the engraver Ferdinando Mori, in Rome. That same year, he opened a private academy in his house in the Chiaia district, which quickly became a gathering place for young Neapolitan painters, including Achille Vianelli, Giacinto Gigante, Gabriele Smargiassi, and Teodoro Duclère. From this nucleus emerged what became known as the School of Posillipo, grounded in the landscape tradition but oriented toward plein-air practice and a more poetic artistic sensibility. Between roughly 1815 and 1830, this group played a decisive role in modern Neapolitan painting, with Pitloo as its central figure.

He was appointed professor of landscape painting at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Naples on 15 September 1824. The work that won him the post, Boschetto di Francavilla, was also a stylistic landmark in his artistic development. He went on to exhibit at the Real Museo Borbonico in 1826 and 1830, confirming his position within the city’s artistic institutions. In 1836 Pitloo wrote to his brother and sister from Naples, reporting a decline in tourism owing to fears of cholera. He also described his own illness during the preceding winter:

“Around mid-January, I came down with a nervous illness that made my work impossible for me throughout the winter, a kind of hypochondria that made me see everything in dark colours.”

We know that on 30 May 1837 he had three works in the exhibition of the Real Museo Borbonico, Veduta dei Ponti Rossi, Veduta con Molino and Veduta della Cava. On 22 June he died in Naples of cholera.

Pitloo: Style and Development

In the introduction to the catalogue for the 2004-2005 Pitloo exhibition at the Museo Pignatelli in Naples, Nicola Spinosa made the following comment on the inclusion therein of Raffaello Causa’s 1956 monograph on Pitloo: he referred to “a text now reprinted without further annotation, since no update is required.” The depth of first-hand knowledge that underpinned that monograph, together with the vitality of its prose, has made it an important source for this introduction.

At the same time, the relative lack of documentation on the artist, together with the strong market for Pitloo’s works, has made the instincts of connoisseurs and astute art-historical judgment essential in reconstructing his legacy. Those wishing to pursue the debate over the legacy in finer detail can refer to the 2004 catalogue. Beyond this, Stefano Causa’s book Ritorno a Pitloo revisits and reassesses both the work of the Dutch artist and the contexts that surrounded the 1956 monograph. The purpose of this article is simply to inform and enthuse an English-reading audience: as such, it is, unashamedly, the work of “a friend of Pitloo” and is expressed with unlaboured, indicative simplicity.

Francis Napier, 10th Lord Napier (1819–1898), wrote of Pitloo, “for his manner is not very careful or scholastic, but full of sensibility.” It is precisely this shift towards sensibility, and away from contrived academic landscapes, or merely artisanal tourist souvenirs, that makes Pitloo’s art so compelling. Raffaello Causa asserted that it was between Rome and Naples, and most significantly in Naples, that the artist’s talent suddenly flourished.

This is not to say that earlier influences were unimportant in Pitloo’s development. In Paris, he studied with Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld (1743–1813) and Jean-Victor Bertin (1767–1842), the latter known as the teacher of Camille Corot. Behind these figures lay the culture of Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes (1750–1819). The great French landscape tradition embodied in such teachers emphasized both the careful study of formal composition and direct observation of nature. This tradition sought to “catch nature in the act” through plein-air studies, although for Bidauld, authenticity required extended outdoor observation and large preparatory canvases. As Désiré Raoul-Rochette noted in his Notice historique: “[Bidauld] went to live for months in front of a view, with a canvas of three or four feet, to paint on the spot all day long … in spite of accidents of weather, and did not leave his post until he had finished his picture.”

One of Bertin’s other notable pupils, Achille-Etna Michallon (1796–1822), also made his way to Naples, entering what Causa described as an “international crucible of artistic languages and aspirations.” Michallon, celebrated for his luminous Italianate landscapes, exemplified the fusion of French compositional rigor with direct observation in the plein-air manner, a sensibility that would have been closely aligned with the emerging Neapolitan landscape milieu that Pitloo encountered.

(Credits: MIA and Fondation Custodia.)

If we look further back into his education, it seems likely that Pitloo’s training in Arnhem provided him with a solid grounding in the work of Dutch masters such as Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) and Jan van Goyen (1596–1656). The latter is cited here as representative of the Dutch tonalist landscape tradition more broadly, which tended toward descriptive fidelity. In addition, the Italianate landscape tradition, particularly through reproductions of artists like Claude Lorrain (born Claude Gellée, 1600-1682), would also have been part of the artistic culture in Arnhem, giving him early exposure to tonal subtlety, compositional balance, and a disciplined approach to observing and representing nature.

(Credits: Fitzwilliam Museum/ National Gallery of London/ Wikimedia Commons.)

While we have already highlighted the significance of Rome for Pitloo, we can deepen this observation by considering the influence of François‑Marius Granet (1775–1849). Granet was a French painter born in Aix‑en‑Provence. He received his early training from the landscape painter Jean‑Antoine Constantin and also spent some time in Jacques‑Louis David’s studio in Paris. Granet moved to Rome in 1802 and remained there until 1824, developing his art. Departing from David’s academic culture, his work began to display novel framings and a Romantic sensibility, combining plein‑air studies with subtle atmospheric effects that emphasized mood and light over narrative or academic convention. The relevance of Raffaello Causa’s suggested affinity between Pitloo and Granet is evident in a single work in The National Gallery, London. Tivoli Roofs, as it is labelled, is a small work (20 × 24 cm) that exhibits all the hallmarks of a progressive outdoor study. Rather than dramatising its subject, the painting celebrates mood and moment over narrative or posed composition.

Tivoli Roofs

about 1810

Oil on paper laid down on canvas, 26 × 24 cm

Presented by the Lishawa family, 2018

NG6672

https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/NG6672

This is a painting which, in an act of sincerity, captures homogeneity, warmth, wear, decay and luminosity. As the National Gallery gloss states:

“Here [Granet] has depicted a tightly packed cluster of houses, roofs and arches. Using dilute paint with a degree of transparency, he has created a homogenous surface of warm browns and greys, punctuated with darker windows and doors. The expressive brushstrokes in the thin paint lend a sense of wear and decay to the buildings. By contrast, the luminous sky is painted smoothly.”

If Pitloo’s reorientation began in Rome, his time in Naples was dynamic and intense, a phase of evolution and experimentation. As Causa defines it, this period is characterised by “a critical restlessness that remains constantly alive through a succession of different phases, each reached and then suddenly rejected and surpassed.”

The pictorial culture that inspired Pitloo’s energetic course of exploration is both too wide and too rich to do full justice to here. However, we can look at some key figures who would have helped to facilitate his journey towards an art that brought studies dal vero into the realm of emotion.

While Joseph Rebell (1787–1828) and Alexandre-Hyacinthe Dunouy (1757–1841) worked firmly within the paysage classique tradition, their landscapes in Naples, city views, coastal panoramas, and countryside scenes, demonstrated a keen sensitivity to light, air, and atmospheric effect. Their careful study of natural illumination and their engagement with on-site observation offered models of tonal subtlety and luminosity that Pitloo could draw upon. Yet, unlike these predecessors, Pitloo went beyond the structured compositions and staged motifs of classical landscape, transforming direct observation into works of expressive immediacy. In this way, Rebell and Dunouy provided technical and perceptual lessons, even as Pitloo’s art transcended the representational habits of the paysage classique, moving toward the freedom and vitality that defined his most innovative and accomplished works, which were largely completed after 1830.

(Credits: Sotheby’s/ Apollo Magazine.)

During his stay in Naples from the autumn of 1820 to the early months of 1821, the Norwegian painter Johan Christian Dahl, a pupil of Caspar David Friedrich, brought with him a sensibility and approach that anticipated some of the qualities later central to Pitloo’s mature work. His landscapes combined direct observation of light and atmosphere with a Romantic attentiveness to mood, producing scenes suffused a palpable current of emotion. At the same time, Dahl’s compositions reveal a careful orchestration of space: he often placed dramatic volcanic or rocky elements in the foreground to frame the view, opening onto expansive bays or distant mountains in the background, creating a sense of depth while guiding the viewer’s eye across the scene. In Naples, his combination of luminous, expressive light, chromatic subtlety, and thoughtfully arranged space would have provided a visual model for the emerging modern landscape tradition, showing how Romantic sensibility and plein-air observation could coexist with a coherence of composition and setting.

(Credits: Lowell Libson & Jonny Yarker Ltd and Daxer & Marschall.)

Pervasive influences from Britain must also have played a significant role in shaping Pitloo’s development as a painter. This, Causa carefully notes, should be defined with some caution. He observes that, in his mature phase, “Pitloo makes a sudden leap toward aims akin to those of the great English landscape tradition… not through derivation, but solely through consonance of spiritual attitude in the same historical moment.”

Thomas Jones (1742–1803), during his Italian sojourn from 1782 to 1784, demonstrated how a seemingly spontaneous view could be elevated to the level of poetry, experimenting with unconventional framing and a sensitive integration of natural and architectural elements. John Robert Cozens (1752–1797), working from sketches made in Italy, completed most of his commissions in the studio, often reworking remembered scenes into simplified and tonally unified compositions in which nature is less described than felt. John Constable (1776–1837) further advanced this sensibility in England, engaging deeply with the study of sky, cloud, and changing weather as expressive agents. Richard Parkes Bonington (1802–1828), trained within the French school, brought a luminous tonal subtlety and refined colouristic technique, while J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851) expanded the expressive and chromatic possibilities of landscape through visionary handling of light and atmosphere. Taken together, these developments disseminated models of technical skill, perceptual sensitivity, and imaginative engagement with nature, which Pitloo would later adapt within the Neapolitan context to form his own distinctive vision.

(Credits: Birmingham Museums/ Yale Centre for British Art/ Royal Academy of Arts, London/ Sotheby’s/ Tate Britain.)

In 1828, Naples and Rome became focal points for contemporary European landscape painting. Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875) visited Naples, while J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851) exhibited in Rome, provoking critical debate among viewers. Corot famously observed that “the real is one part of art; feeling completes it,” emphasizing the fusion of observation and sensibility, while Turner transformed the idealised light of Claude Lorrain into a visionary, almost elemental force, one that often dissolved form and place. According to Raffaello Causa, Pitloo assimilated lessons from Turner in his rendering of air, creating atmospheres rich in chromatic depth, yet retaining the clarity of form and place. At the same time, he also suggests, Corot’s small Italian sketches, or pochades d’Italie, provided a model for translating the cooler, northern qualities of Pitloo’s handling of light into the warmer, more luminous tones of the southern Italian landscape, enabling him to achieve the distinctive immediacy and tonal richness that characterise his mature work.

(Credit: National Gallery, London.)

The variety and complexity of cultural exchange within the landscape tradition during the last decades of the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth was the theme of an excellent exhibition held in Washington, Paris, and Cambridge between 2020 and 2021. The exhibition, True to Nature: Open Air Painting in Europe 1780 to 1870, aimed to convey the “euphoria” experienced by artists of this period as they were “sitting before their motif, moved to record their perceptions in idiosyncratic and inventive ways.” The dizzying level of change and exchange in both Europe as a whole, and in Naples in particular, is salutary when considering a figure like Pitloo. Given the scarcity of documentary evidence available to define the precise details of his development and production, a consideration of some of his more securely attributed works provides a useful grounding.

Pitloo: selected works.

La caccia agli Astroni di Ferdinando I

( La caccia agli Astroni di Ferdinando I / The Hunt at the Astroni by Ferdinand I (c.1820), oil on canvas, 110 x 91 cm, Sorrento, Museo Correale di Terranova. Author’s photograph.)

In commenting on La caccia agli Astroni di Ferdinando I (c.1820), Raffaello Causa’s observations remain singularly illuminating. He highlights the way Pitloo combines elements of an older, commemorative pictorial tradition with a new urgency of nature, revealed as mysteriously alive and autonomous in its expressive force. Although here Pitloo still bears traces of half a century of courtly imagery of hunts and royal pastimes, little remains of the old celebratory taste. Instead, air and light dominate the scene. The strong backlighting and the luxuriant woodland threaten to engulf the hunting party altogether, granting nature an ancient primacy over human activity.

In this sense, Pitloo’s realism is not merely descriptive but is a step on the path to a radical depiction of wild, unpopulated natural scenes. An interesting parallel can be found in Dominique de Font-Réaulx’s comments on Courbet’s landscapes in the catalogue Courbet e la Natura (2018), where she describes a world that seems to open and close before the viewer, alive on the surface, yet rooted in something primordial and unfathomable.

(Credit: Washington Museum of Fine Arts.)

Although Courbet and Pitloo differ in working methods and historical context, both convey a sense of nature as a force that exceeds human narrative and, in Courbet’s case, human presence. Pitloo does not bend colour and light to the service of spectacle. He allows them to assert their own authority. The result is a pictorial language that resists courtly celebration and moves toward something more modern in spirit, where nature is not a backdrop but a presence. In that respect, the painting is innovative in handling and genuinely subversive in conception.

Pitloo: Vedute di Castel dell’Ovo

(Credits: Wikimedia commons.)

Both paintings of the Castel dell’Ovo from Santa Lucia appear to date from around 1820 and both seem to originate in direct observation from life. They share the same vantage point and underlying perspective, with the castle anchoring the composition and a scatter of sailing vessels and small fishing boats moving behind and in front of it. Yet despite this shared structure, the two works articulate the scene in different atmospheric and emotional keys, belonging to different times of day.

Making a very tentative observation on colour, based solely on the juxtaposition of reproductions in the 2004 Pitloo monograph, the Roman painting seems to adopt a marginally cooler palette and a slightly more contemplative mood. (It needs to be stated that the images here do not make such a clear distinction, hence my reservation.)

In all events, an air of serenity and languor in this rendering is arguably reinforced by the tree trunk in the left foreground, which leans inward towards the centre of the composition. In the two versions, the human activity varies: in the Roman version there is a small group of people talking in the central foreground, while fishermen are seated, tending their nets and guiding a sailing boat to shore. Distant hills appear to the left of the Castel dell’Ovo, emerging through a relatively open and restrained cloudscape.

By contrast, the Torre del Greco painting seems warmer and more radiant in colour. The dominant tones shift toward oranges and golds, and the light effects are more poetic. The trees at the left are strongly backlit. Their fronts fall into deep shadow, while the deeper trees have filigree-like tracings of golden light around the leaves. Here the foreground is animated differently. Two fishermen are shown hauling a small boat up onto the shore, their coordinated labour giving the scene a sense of physical effort and narrative immediacy. The brilliant whites of the other fishermen’s clothing punctuate the shadowy foreground with sharp highlights.

Atmospherically, the Torre del Greco version is more active, rather than simply serene. A larger cloud mass gathers on the right, and the cloudscape overall is more extensive. As a result, the hills visible in the Roman painting are obscured here, overlaid by shifting vapour and light. Mount Vesuvius appears slightly larger and displaced marginally to the left, and it merges more fully with the surrounding cloud formations, blurring the boundary between landform and atmosphere.

The Roman work (completed for the Jacobite peer and collector James FitzJames Stuart, Duke of Berwick) feels slightly more self-contained and reflective. The Torre del Greco painting, with its different time setting, transforms the same viewpoint into a warmer, more animated and theatrical experience of Naples, shaped as much by light and weather as by topography.

While both works show Pitloo’s growing command of plein air study and convey emotion through their depiction of colour and atmosphere, the composition in each retains a more traditional and formal shape.

Il boschetto di Francavilla al Chiatamone (1824)

(Credit: Gallerie d’Italia.)

In Il boschetto di Francavilla al Chiatamone (1824), Pitloo departs decisively from the classical landscape tradition of idealised structure. Rather than presenting a staged vista, he situates the viewer within the scene, using dense foreground vegetation and an oblique, unprivileged viewpoint to create a sense of participation rather than organisation. Light and atmosphere are treated not as descriptive accessories but as primary agents of form, softening contours and dissolving rigid spatial hierarchies. Architecture is absorbed into the natural environment rather than imposed upon it, reinforcing a vision of landscape as experienced rather than constructed and ideal. The integration of landscape and architecture from a spontaneous viewpoint is something visible in the work of both Thomas Jones and François Marius Granet.

(Credit: Solo Arte.)

Pitloo’s painting marks a shift from landscape as intellectual composition to landscape as perceptual encounter, one of the defining innovations of Pitloo’s Neapolitan practice.

Il boschetto di Francavilla al Chiatamone signals a turning point both in Pitloo’s career and his style, establishing his move beyond the illustrative conventions of earlier foreign landscape painting in Naples. The work won him the chair of landscape painting at the Royal Academy, allowing him to succeed Giuseppe Cammarano. It depicts a section of the Villa Reale’s little wood, the no longer extant Casino di Francavilla, situated between the Castel dell’Ovo and a small pool formed by the Chiatamone spring. While the composition retains some affinities with classical landscape, it decisively asserts a more immersive and perceptual approach to nature.

Pitloo, drawing perhaps on Corot as well as on his Parisian training under Bidauld and Bertin and his familiarity with the post-Hackert Neapolitan school, renders the humid, dense foliage of the foreground with fluid, expressive strokes, while distant mist rises to articulate layers of space, framing buildings against a luminous sky. As Raffaello Causa observes, these atmospheric effects reveal a sensitivity to light, air, and depth that was largely unprecedented in Naples, reviving subtle perceptual nuances that had been almost forgotten. By integrating architecture into the natural setting and using light and tone to guide perception, Pitloo transforms the landscape into an absorbing, subjective experience, consolidating Il boschetto as one of the defining works of his early Neapolitan practice.

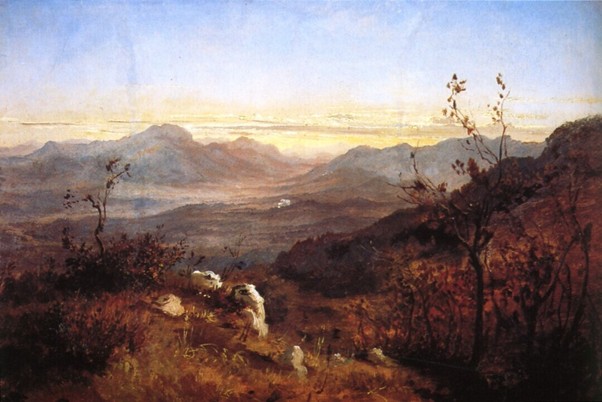

Paesaggio al tramonto (1830)

(Credit: Gallerie d’Italia, Napoli.)

In Paesaggio al tramonto (1830), Pitloo positions the setting sun at the centre of the composition, allowing its last rays to bathe the deeper landscape in a golden, fleeting light. The hillside is painted in autumnal reds and golds, the burnt earth punctuated by white stones at the centre of the slope, which catch the light and draw the eye. As the landscape recedes, colours cool and the air seems to grow cooler, so that depth is conveyed as much through the changing sensation of light and temperature as through spatial recession. Pitloo does not anchor the scene to a precise location; rather, he captures a moment of emotional engagement with nature, where the interplay of sun, colour, and atmosphere evokes both the visual beauty and the ephemeral feeling of the landscape at sunset.

Le torri del Corpo di Cava/ The Towers of the Corpo di Cava (1831)

(Credit: Gallerie d’Italia, Napoli.)

In Le Torri del Corpo di Cava (1831), Pitloo captures the austere landscape between Cava dei Tirreni and Vietri sul Mare. Amber light suffuses the valley, bridge, trees, and distant herd, creating a tonal harmony that conveys both depth and atmosphere. The central tower, deliberately placed, provides a compositional pause, anchoring the eye without dominating the scene. While the work retains a sense of eighteenth-century order, it gestures toward a more Romantic sensibility, perhaps informed by Turner’s exhibition in Rome in 1828. The painting marks a transitional moment in Pitloo’s work, where classical perspective and formal structure begin to yield to the expressive possibilities of light and atmosphere.

Il ponte e la chiesa di San Francesco a Cava dei Tirreni/ The Bridge and the Church of San Francesco at Cava dei Tirreni (1836)

(Credit: Gallerie d’Italia, Napoli.)

In Il ponte della chiesa di San Francesco a Cava dei Tirreni (c. 1836), Pitloo revisits a well-known view, producing a smaller canvas with thicker paint and rapid, broken brushstrokes. The light no longer relies on the pinkish glow of sunset; instead, it is observed directly from nature, translated into the handling of paint itself. Amber tones and natural colours are rendered with immediacy, creating a concrete sense of the landscape while moving beyond the subtle lyricism of his earlier works. The view of Cava dei Tirreni was popular with patrons, and Pitloo’s repeated engagement with it contributed to its role as a model for other artists of the School of Posillipo. In the view of Raffaello Causa, this and some other late landscapes of the region represent Pitloo’s most intense explorations of expressive effect: a heightened restlessness, dramatic accentuation, and dense, energetic paint application that convey tension and force rarely achieved in Neapolitan landscape painting. While Causa’s assessment emphasises extremes, it highlights the painting’s place in a transitional moment where direct observation, material engagement, and expressive intensity converge in a modern, personal vision of the local terrain.

Pitloo: skies

His pencil is always true to general effects, whether his canvas represents the prospect basking in the midday brightness of the Italian sky, the waves flashing in the train of the level sun, or the fields refreshed and steaming in the dawn; every colour finds its counterpart on his palette, and no aerial magic is so evanescent as to elude his subtle imagination.

Francis Napier, Notes on modern painting at Naples (London, 1855).

(Credits: Fondation Custodia, Collection Frits Lugt/ Antonacci Piccirella Fine Art.)

These three small works by Pitloo illustrate his plein-air capture of light and atmosphere. They include a pendant pair, Sunrise and Sunset, from the Frits Lugt Collection at the Fondation Custodia, and a Sunlit evening cloudscape from a private collection.

In Sunrise, to paraphrase Ger Luijten from the True to Nature exhibition catalogue, the thinly applied greens and dark browns in the foreground reveal the width of the brush, while scratches in the wet paint hint at the use of the pointed wooden end. The sky shifts from pale rose and clear blue to a saturated light blue at the top, with clouds reflecting the darker tones beneath them. Nearer clouds float just within reach, while those farther away are hidden in a pinkish glow. A left-to-right blue stroke marks the sea, and the slightly uneven horizon suggests rapid, on-the-spot execution. The overall effect breathes the cool, promising atmosphere of a summer morning.

In the Sunset pendant, the horizon seems to be on fire, and the reddish-orange is reflected in the sky. Pitloo placed a group of trees in the foreground to create depth. A strip of clear blue suggests the sea, and the sky is built up with a richness under which the sun goes down with a touch of drama, while a crescent moon has taken its place. The two signed pictures are a rarity in the artist’s oeuvre. As Luijten observes, they show how Pitloo had a remarkable sensitivity to light and colorito, and how he could value the spontaneity of his brushwork as an end in itself.

The same scholar also comments that there is ‘even more exaltation’ in the more stretched Sunlit evening cloudscape that is the final illustration in our series here. This work, also signed, appeared on the private market relatively recently and entered a private collection.

[Producing these essays requires care, time, research, and resources. Contributions to help sustain this exploration would be greatly appreciated.]

https://donorbox.org/inner-surfaces-resonances-in-art-and-literature-837503

Bibliography

As ever, any errors and infelicities in this article are mine. Readers who wish to deepen their knowledge can refer to these books.

Cassani, S., In the Shadow of Vesuvius (Napoli, 1990).

Causa Picone, M. and Causa, S. (eds.) Pitloo: Luci e colori del paesaggio napoletano (exhib. cat., Museo Pignatelli, Naples 2004).

Causa, R., Pitloo (Napoli, 1956).

Causa, R., La Scuola di Posillipo (Milano, 1967).

Causa, S., Ritorno a Pitloo (Napoli, 2004).

Herring, S. and Mazzotta, A., Corot to Monet: French landscape painting (New Haven and London, 2009).

Luijten, G., Morton, M. and Munro, J. et al. True to Nature: Open-air Painting in Europe 1780-1870 (London, 2020).

di Majo, E., Anton Sminck Van Pitloo (1791-1837). Un paesaggista olandese a Napoli: ventisette opere ritrovate. Prefazione di M. Causa Picone (Rome, 1985).

Middione, R., and Daprà, B., Reality and Imagination in Neapolitan Painting of the 17th to 19th Centuries (Edinburgh Festival Society, 1988).

Noon, P., Richard Parkes Bonington: the complete paintings (New Haven and London, 2008).

Olson, R. (ed.) Ottocento (New York, 1992).

Pacelli, M. L. (ed.) Courbet e la Natura (Ferrara, 2018).

Picone Petrusa, M., Dal Vero: Il paesaggismo Napoletano da Gigante a De Nittis (Torino, 2002).

Sisi, C., La pittura di paesaggio in Italia – L’Ottocento (Milano, 2003).

Spinosa, N., Art Treasures of the Banco di Napoli (Napoli, 1984).

Sumner, A. and Smith, G. (eds.) Thomas Jones: an artist rediscovered (New Haven and London, 2003).