‘…a dodici anni mi recai a Napoli, dove rimasi fino ad adulto. Io giunsi a Napoli in pessimo arnese. La fame era allora molta, ma scarsa la fama…’

‘…at twelve years old, I went to Naples, where I stayed until adulthood. I arrived in Naples in terrible shape. At the time, there was a lot of hunger, but little fame…’

(Quoted Virno (2019) vol. 2. 503.)

Lo scugnizzo, 1868 (Private collection) offers us an excellent introduction to Antonio Mancini (1852-1930); it is a noteworthy work of his early Neapolitan phase, prior to his first visit to Paris in 1875.

This was Mancini’s first large-scale painting and it was significant enough to draw his teachers, Filippo Palizzi and Stanislao Lista, to his improvised loft studio, part of the family home in Vico Majorana in Naples. Domenico Morelli must also have seen Lo scugnizzo and it is to this work that Dario Cecchi connects Morelli’s Neapolitan dialectal exclamation, ‘A’ stu schugnizzu dico bene, nun saccio pròpete che l’aggiu ‘cchiù a ‘mparà’, indicating that he no longer knew what to teach his talented pupil.

The painting, realised in Mancini’s sixteenth year, is certainly a testament to his precocious talent. It seems to capture the formative emotional experiences of his youth and to mark a definitive point of departure for a significant body of works which were to follow. Dario Cecchi (1918-1992) wrote an excellent biography of Mancini which allows us to see how the artist’s impoverished early years can give sense and depth to this distinctive masterpiece.

There can be no doubt about the importance of autobiographical understanding here when we know that, in later life, Mancini himself said, ‘Lo Scugnizzo ero io’, ‘I was the urchin.’ In this powerful affirmation he was also indirectly revealing his lifelong feeling of inferiority in the presence of the wealthy. The antiquarian Augusto Jandolo recalled Mancini saying, ‘Vulgarity is often the daughter of poverty, and poverty has always been my closest relative.’

The overall importance of this work is underscored by the fact that the Mancini family made a number of attempts to buy it back; Antonio’s nephew finally managed to purchase it in 1920. When the artist saw it again, he declared how he painted it in a loft at the age of 16 when he was famished. (…Avevo sedici anni: l’ho fatto dentro una soffita, con una fame!…)

Mancini and Morelli; capturing emotion on canvas.

In outline, the painting depicts the life-size image of an out-of-place street urchin (scugnizzo), dressed in rags, standing in a fashionable bar, beside the discarded remains of a party. The essential polarity created is therefore between poverty and wealth: a poor boy contrasts with objects from a world of careless indulgence.

Among the various achievements in Mancini’s painting that would have appealed to Morelli must have been the way in which it realises an intense emotionality. At the end of his Roman residency, Morelli was required to produce a showcase work. Among the requirements that led to Gli Iconoclasti (The Iconoclasts) (1855), was that it should convey an intense emotion, a ‘martyrdom of the soul.’

In order to convey such truthful feeling, Morelli entered the emotions of his historical subjects through imagining characters in his own time. Thus, the Byzantine monk and painter St. Lazarus (who was persecuted during the iconoclastic period of the 8th and the 9th centuries) was imagined as a ‘young liberal,’ while the role of a brutal executor was realised through contemplation of ‘the character type of a policeman.’ This anecdote illustrates Morelli’s defining combination of fantasy and realism.

The emotional drama of Morelli’s ‘Gli iconoclasti.’

(Credit: Wikipedia)

But Mancini did not need to find such means for imaginative empathy. He was a poor and hungry youth and he had been a poor and hungry child. When very young, he witnessed infant mortality in the orphanage run by his aunt Chiara in Narni. Moreover, in the Naples of the Ottocento, he would have been surrounded by the poverty, neglect and exploitation of children.

On the subject of hope and a precarious childhood.

Mancini was an earnest student, but one dependent on education where and when he could find it. He found it with the religious orders of the Scolopi (Piarists) in Narni and the Gerolomini in Naples. He must have hoped to find progress and stability through these opportunities and, in relation to this, there are further traces of his childhood experience in another work, completed a year before Lo scugnizzo.

Fanciullo napoletano (Neapolitan Boy) was finished in 1867 [See, Virno 2019, cat.13]. This is a representation of an innocent boy ready to leave for school with a bundle of books, and a flower stem in bloom, under his arm. There were to be other, later works, of young students with books; the theme was obviously close to his heart. When he painted Lo scugnizzo Mancini had both talent and the motivation for success but nevertheless, this might not have been enough.

Dutiful towards his teachers (and mindful of the expectations that his parents were investing in his talent) he was also in an extremely uncertain situation. Anyone who has read works by Charles Dickens, and knows anything about the author’s childhood, could quickly imagine Mancini’s circumstances at the age of sixteen. The relics of a party in Mancini’s painting are like the brightly lit and food-laden windows of A Christmas Carol to London’s poor: the abundance is alluring, within apparent reach, but ultimately inaccessible. In 1865, Mancini used to loiter outside the Caffé d’Europa in Naples, in the hope that one of the painters would invite him to eat with them. ‘Sometimes [he] was invited’ he said, only to add, ‘but more often not.’

The precariousness of the young painter is the precariousness of Lo scugnizzo. There is no grand Morellian heroism here but rather the everyday pathos of a vulnerable street urchin. This mood matches the fragile uncertainty of our aspiring young artist and, in emotional terms, we are not that far from the dignity in suffering portrayed in religious works of the Neapolitan Seicento.

Talent transforming scarcity.

We can see this painting as demonstrating just how far scarcity can be elevated and transformed by talent. Tomaso Montanari’s 2016 television monograph La vera natura di Caravaggio shows us how the rich visual and emotional variations found in Caravaggio’s art in Rome were probably born in a basement studio, with a small range of props and a limited repertoire of low-cost models. In a similar act of creative magic, in his loft studio, with a model taken from the streets, Mancini elevates the dramatic status of his scugnizzo. His skill as a painter and the simple compositional choice of juxtaposing the boy with objects and décor associated with an extravagant lifestyle produces a compelling masterpiece.

Material detail and realism.

While the fabrics and the decoration of the bar are sumptuous, some of the beautifully rendered lustre and texture derives from more mundane objects, such as the discarded paper, the foil on the bottles (with their commercial labels) and the reflections in the empty glasses. In all events, beside the boy and at his feet, we have a wonderful set of effects of light and texture, as well as bravura still-life studies.

We can add to the list of skilfully depicted objects, surfaces and textures: we have padded-fabric wainscoting, studded at the top, with a frill trim at the bottom; masks and costumes; richly patterned damask wallpaper; glass seen through glass; decorated China cups, in different positions; an abandoned photograph, photographs in a magazine or newspaper, and strewn cut flowers. This is a declaration of what the young painter is capable of and we can only guess that the attention to such a range of fine realistic detail must have been a particular delight to the eyes of Filippo Palizzi.

The difficult face of child poverty.

Mancini employs a strong light, which rakes in from left to right. One consequence of this is that the most telling planes of the boy’s face are partially hidden, by being in a right profile which is retreating into shadow. What is still noticeable is that there is something delicate and detached about his expression and line of sight. The simplicity of the face allows it to catch a range of projections from the viewer, who is set an emotional challenge.

Should the admirer of this painting affirm the ephebic beauty and fragility of the boy, or should they shake themselves out of such effete aestheticism and be mobilised by the sight of social injustice? Perhaps the apparent dilemma is merely the fruit of language as, in vision, everything can reach us at once and one thing need not be separated from another.

Moreover, if we compare the scugnizzo’s expression to what Linda Nochlin calls a proto-documentary photograph from 1910, by Lewis Hine, then we might simply decide that Mancini achieved a strikingly faithful portrayal of reality. This is because Hine’s frontal portrait ‘Addie Card, 12 years old, anemic spinner in North Pownal Cotton Mill, Vermont,’ silences us in a similar way to Mancini’s painting; through its subtle and haunting representation of youthful suffering. As suggested in Auden’s poem, Musée des Beaux Arts, great tragedy is often muted by its existence within a context of indifference and daily routine.

(The photograph is in The Metropolitan Museum of Art (see link below) and is also reproduced in Nochlin, 2018, p. 106.)

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/285844

Mancini and artistic tradition; observations on light, colour and mood.

The Seicento artistic heritage of Naples lays some claim to the colour and mood of this work of art, along with its chiaroscuro lighting discussed above.

The tonalities of the Neapolitan Baroque share the stage in this emotionally charged but finely modulated scene. There are earthy hues of red in the painting which combine with gold, yellow and white. These colours, and the boy’s sallow skin, are redolent of the seventeenth century: we can also feel the influence of Naples in Mancini’s use of Pompeian red and Pozzuoli Earth. The palette has a richness and luxury which is nonetheless tuned to a register of quiet sorrow.

There is an emotional kinship and affinity between Lo scugnizzo and the pictorial world of Bernardo Cavallino (1616-1656). I am referring to the Cavallino perceived by Raffaello Causa as an ‘evocative and anxious personality, tender, mournful and sentimental.’ A painter who confronted subjects in an ‘intimist key.’ (See Introduction in Lurie, A and Percy, A (eds.) Bloomington, 1984.) Without falling into an excess of sentimentality, we are presented with both warmth and want.

Bernardo Cavallino, La pittura: An Allegory of Painting. Collection Novelli, Naples.

(Credit: Mutual Art)

Bernardo Cavallino, Santa Cecilia (1645 ca.), Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

(Credit: Wikipedia)

Lo scugnizzo – comparative meditations on expressive posture and the statuesque.

Mancini’s street-child has an overtly statuesque quality, almost as if he is a wax figure placed in a maquette. His right profile creates a sensation of movement against the alignment of the feet, which face to the left at about 45 degrees. This is suggestive of a division in the boy’s attention; he is reticent or hesitant. It is as if the remnants of the party belong to another world that is forbidden.

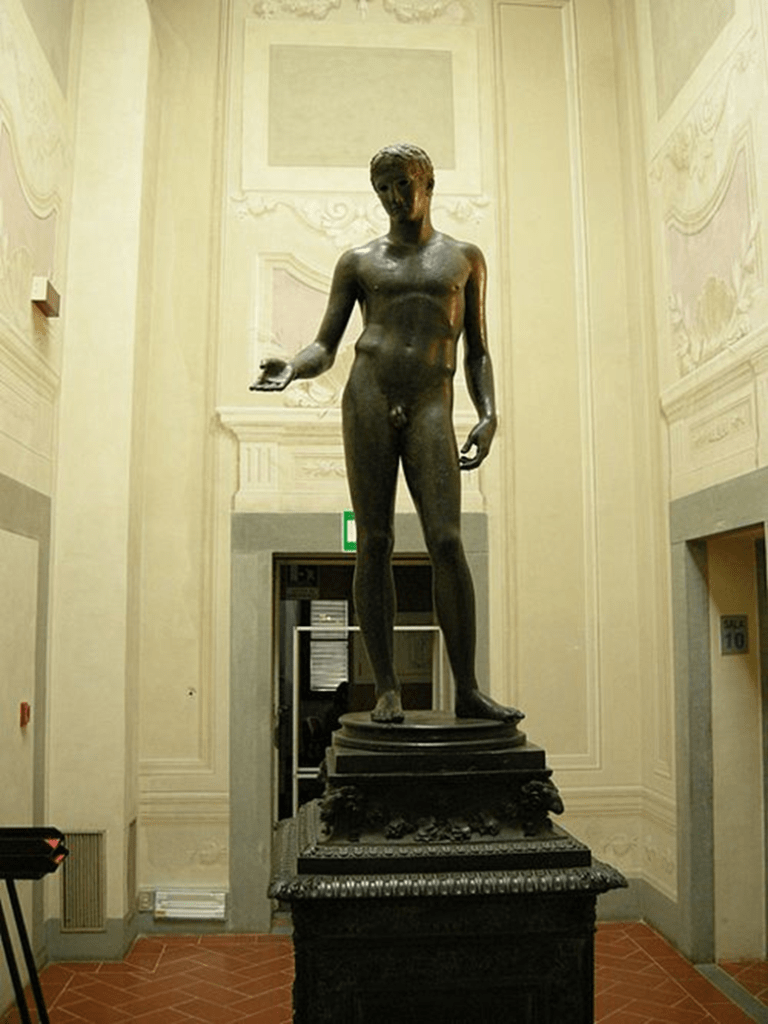

There is life too in his flexed right leg, but the potential for contrapposto is not realised, as this is not a conventionally heroic, or even an especially graceful stance. In a classical, or classicizing, context one could reasonably expect a hand gesture to accompany a youth in such a flexed, asymmetrical posture. This is certainly the case with the Idolino of Pesaro and with Vincenzo Gemito’s Narciso (Narcissus) of 1886.

Idolino di Pesaro (Museo archeologico nazionale di Firenze.)

(Credit: Wikipedia.)

Gemito Vincenzo, Narciso (1886), Villa Pignatelli, Naples.

(Credit: Catalogo generale dei Beni Culturali.)

But in Lo scugnizzo all mobility and swagger has been cut short: there is no pointing or outstretched hand, no tilting hip and no eloquent void between the arm and body. Instead, the contrapposto dynamism somehow gets trapped as it travels towards his torso. Rather than energy moving out to the extremities, the fingers are interlocked and his arms hang down before him. This is not youthful cocksureness, it is rather the diffidence of an endearing but downtrodden child who looks as though he might step away in shyness at any moment. In mood we are closer to Murillo’s street-children, or the adults in Millet’s L’ Angelus.

Looking forward in time, less than a decade after Mancini’s Lo scugnizzo, Rodin offered a sculptural vision of pathos that breaks the stasis of hopelessness and rises into the torso. In his statue L’Age d’airan (first exhibited as Le Vaincu; modelled in 1876 and cast in 1906) the emotions of a vanquished adult break through into movement and gesture in the upper body. Realism here takes us into another dimension of emotional complexity and ambivalence, as we have an indeterminate awakening into what could be release, or simply mounting suffering. What feelings are innocently assimilated, and perhaps only partially comprehended, in Mancini’s child seem to have graduated into a fully embodied reaction in Rodin’s adult.

L’Age d’airan (The Age of Bronze) 1877, by Auguste Rodin. Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden.

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons.)

True feeling in an uncertain setting.

A game of perception is played out in Mancini’s inclusion of the edges of picture frames on the red wall in his background. Including evidence of paintings is part of the lavishness of the scene but we can also see it as a device that renders the picture more real. If the world of paintings is behind the boy, then what we are seeing must be reality. However, in terms of overall composition, we are not transported into a plausible space. To make the situation feel credible, we would have to invent some form of justifying narrative. We could decide that it is about a boy who has wandered into a bar which had a party the night before; alternatively, we could call it a religious allegory about restraint, or temptation. But there is something reductive in any such invention and it is better to leave the image as puzzling and unsettling, as that is part of its power.

Nothing lasts; how Lo scugnizzo can change the way we look at Alla Dogana (The Customs).

Lo scugnizzo is painfully ephemeral. The party it alludes to has already finished, objects lie abandoned, and the revellers have gone. The artifice of the pictorial arrangement also reinforces a sense of transience: we know that it will only last for as long as the artist requires, then the real-world scugnizzo will go back to the street and any props will be packed away.

With this in mind, it is interesting to see how the work can shift our viewing of Mancini’s Alla Dogana (The Customs) (1877). On its own, the latter work might seem to be a testimony to an age of travel, wealth, and cosmopolitan living. The Customs is certainly a picture which aims to appeal to the Parisian marketplace. The woman who sits in the painting is well-dressed, apparently self-possessed and is perched on a trunk which bears testament to her wealth and the ability to afford to travel. She is, we might think, just waiting to head off to new lands and new experiences. The room she is in has the appeal of domestic sophistication and does not resemble a customs office; it has fine, lined wallpaper, an oil painting, and a delicately crafted writing desk.

However, there is an uneasy disorder and incompleteness in the left of the canvas which might invoke an underlying sense of the precarious nature of human life; something arguably intrinsic to Mancini’s personal experience and, by extension, to his art.

https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/antonio-mancini-adieu-paris-the-customs

Here a crate has either been opened, presumably for a customs inspection, or it has not been packed to completion. Piled together in a box and padded with old newspaper, we see a jumble of objects which, at one level, are visually more intriguing than looking at the lid of a closed crate or suitcase. There is also something dynamic and transitional about this detail which catches our attention.

However, at the same time, the objects have lost the kind of appeal that once led to their acquisition. Like the remains of the party in the Lo scugnizzo, these are objects which are out of use; they are no longer animated or given meaning through social usage. There is something sad, unrewarding and superfluous about them. The woman in the picture might be in a less enviable situation than we first thought. After all, she is quite literally spaesata (lost/ out of her familiar surroundings). She is neither at home, nor at her final destination and, in emphasis of this fact, one of the words that is visible in the newspaper packaging is déménagements.

In the setting of the painting she is in some kind of holding place. The ambiguous room, somewhere between a customs office and a living room, is ultimately a studio construct. This study could be a return to, and a reworking of, the feelings of the displaced, socially excluded, and vulnerable child in Lo scugnizzo.

Moreover, if we accept Hiesinger’s conjecture that the model in this painting is Mathilde Duffaud, Vincenzo Gemito’s first love, then we are in unsettled circumstances. (The idea is plausible, as the model strongly resembles Gemito’s two bronze heads of Mathilde, one on a cast cushion and the other on a plinth.) Mathilde would have just arrived in Paris by the end of 1877, the year of the painting, to be reunited with Gemito. She had an illness that was to necessitate the couple’s return to Naples in 1880 and by 1881 she had passed away in Herculaneum. An awareness of both the alienation in Lo scugnizzo and the biographical reality of Mathilde’s ill health, and her impending return to Naples, destabilises and complicates our understanding of what we are seeing.

Conclusion: a studio misère and the inspiration and heroism of childhood.

Linda Nochlin’s study of the visual representation of misère in the nineteenth century opens with a definition of the term by a young French sociologist, Eugène Buret. He argues that misère is distinct from poverty as it is a ‘pain felt morally’, and its ‘pain penetrates to the moral sense.’ Buret’s qualification is highly relevant to Lo scugnizzo which probes a viewer’s moral and emotional core.

While parts of Nochlin’s study of nineteenth-century art offer some possibility of parallels with Mancini, most notably the chapter on the artist Fernand Pelez (1848-1913), most of the images considered deal with small groups of the urban poor and the rural poor; people in the streets and in the fields. There is also an examination of representations of the Great Irish Famine (also known as the Great Hunger) which occurred between 1845 and 1852. The images of this extensive tragedy are considered to be the paradigmatic example of nineteenth-century misery.

Within this great social sweep of urbanisation, industrialisation and poverty there were also more intimate representations of struggle and social difference; more intimate domains, such as brothels, cafés, music halls and dance studios. Mancini’s Lo scugnizzo offers his own microcosm for the age; a studio misère, a solitary study of psychological and dramatic intensity realised with a poetic refinement. It is a work of great originality and sensibility, innovative and apt for its time, while still influenced by tradition.

Wordsworth’s short poem of 1802 My Heart Leaps Up declares that ‘The child is father of the man.’ The same poem also connects a sensibility for beauty with the state of childhood. There is a similar idea in Baudelaire’s The Painter of Modern Life where he declares that ‘genius is no more than childhood recaptured at will.’ He also refers to ‘that stare animal-like in its ecstasy, which all children have when confronted with something new.’ Mancini’s precocious talent enabled him to articulate his genius while still close to the youth which was its source. His own childhood and an empathy for the scugnizzi that modelled for him are of seminal importance in his art, as are the sentiments that both he and they embodied. Mancini’s Lo scugnizzo is part of that understated nineteenth-century heroism in art; one which stood apart from the accoutrements of status and glory and chose instead to be rooted in contemporary social reality. It is a heroism that might simply be the maintenance of a dignity of being. Here, the boy’s quiet forbearance is innocent, devoid of reaction and reproach: such qualities will need to come from the concern of the viewer.

Producing these articles requires care, time, research, and resources. Contributions to help sustain this exploration would be greatly appreciated.

https://donorbox.org/inner-surfaces-resonances-in-art-and-literature-837503

Bibliography

(I have been reliant on the following texts but any errors and infelicities are my own.)

Baudelaire, C., The Painter of Modern Life, trans. P. E. Charvet. London, 1972.

Bellenger, S. (ed.) Napoli Ottocento. Milano, 2024.

Carrera, M. (et al.) Antonio Mancini/ Vicenzo Gemito. Milano, 2023.

Cecchi, D., Antonio Mancini. Torino, 1966.

Hiesinger, U., Antonio Mancini, 19th Century Master. Philadelphia, 2007.

Lurie, A and Percy, A (eds.) Bernardo Cavallino of Naples (1616-1656). Bloomington, 1984.

Martorelli, L. (ed.) Domenico Morelli e il suo tempo. Napoli, 2005.

Nochlin, L. Misère: The Visual Representation of Misery in the 19th Century. London, 2018.

Nochlin, L., Realism. London, 1971.

Valente, I. ‘Verità, spiritualità e mito. L’opera di Domenico Morelli’ in Napoli Ottocento (ed.) Bellenger, S., Milano, 2024.

Virno, C., Antonio Mancini, catalogo ragionato dell’opera 2 voll. Roma, 2019.

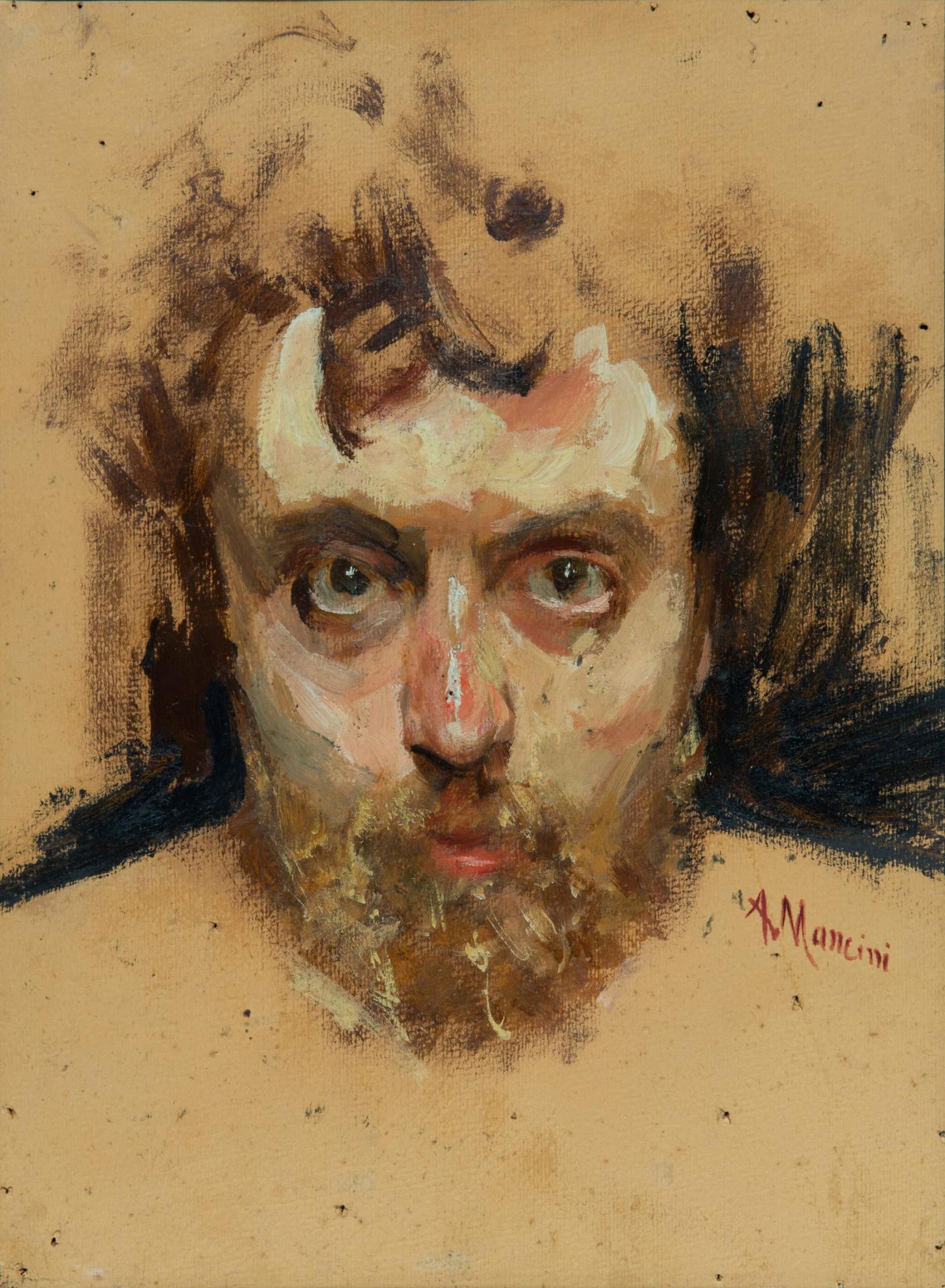

(Feature image credit (Mancini’s self-portrait) – Antonacci Lappicirella Fine Art: https://www.alfineart.com/about-us/ )

(The Scugnizzo has also been alternatively named as follows: Ama il prossimo tuo come te stesso/ Miiseria e stravizio/ Lendemain de fête/ Il terzo comandamento/ Fremito di desiderio/ Desideri.)